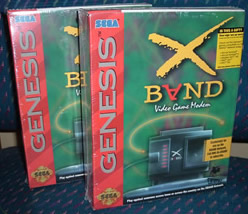

Long before there was Xbox Live or the Playstation Network, 16-bit gamers had the Xband. Long distance gaming had long been trying to become viable, with consoles like the Atari 2600 and the NES both taking unsuccessful stabs at making it a reality. It wasn’t until Catapult launched the Xband in 1994 that things were finally taken to the next level and online gaming through consoles finally became something viable. During its three-year run, the Xband made serious strides towards bringing gamers closer, and it laid the foundation for the online networks that millions of gamers enjoy today.

In addition to great programmers like David Ashley, one of the people instrumental in Catapult’s success was Konstantin Othmer, a former Apple employee who saw the potential of giving video game consoles online play. Starting at Catapult as its Vice President of Software Development, Othmer eventually went on to be in charge of all product development and was at the forefront of the company’s landmark work in making online play a reality. Currently, he is the founder and CEO of Core Mobility, one of the premier companies delivering and supporting valuable end-to-end services for mobile devices.

In addition to great programmers like David Ashley, one of the people instrumental in Catapult’s success was Konstantin Othmer, a former Apple employee who saw the potential of giving video game consoles online play. Starting at Catapult as its Vice President of Software Development, Othmer eventually went on to be in charge of all product development and was at the forefront of the company’s landmark work in making online play a reality. Currently, he is the founder and CEO of Core Mobility, one of the premier companies delivering and supporting valuable end-to-end services for mobile devices.

Mr. Othmer joined Sega-16 for some Q&A about the Xband and Catapult.

Sega-16: How did you start at Catapult?

Konstantin Othmer: I had spent five years at Apple and was on a six week sabbatical – a very cool perk you get at Apple! Kip Olson and I were chasing snow throughout Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming. Bruce Leak joined us for part of. He had recently founded a video game company, and we were discussing opportunities as we were riding up a chair lift in Breckenridge, CO. I was pretty excited about joining his company, and he asked what I would work on. I suggested networking the games so you could play over phone lines. He said that Steve Perlman and Steve Roskowski (Rosko) were working on exactly that in their spare time and were considering starting a company around the idea. I was so excited, I wanted to jump off the chairlift and get started. I finished my skiing sabbatical and called Perlman as soon as I got back to the bay area.

I went to Perlman’s house to check out what he had been up to, and they, together with Tim Cotter, had basic synchronization of Mortal Kombat working on a Sega (Genesis). I was so excited about the whole thing I wanted to jump in immediately. Perlman and Rosko hadn’t left their jobs at General Magic yet, but had lined up the rest of a management team and had some interest from Marvin Davis to fund the venture.

On April 1, 1994 Rosko and I started working on Catapult full time, along with Shannon Holland who I worked with at Apple. Our goal was to ship the modem for the 1994 holidays, so we had our work cut out for us. Rosko built the hardware and I worked on the software. When Shannon and I left Apple, a number of people came over to see what we were up to and some of the best Apple engineers joined us. David Jevans built the network side of the service, and Chris Yerga, Andy Stadler, Josh Horwich joined within the first few weeks.

One hire that was particularly interesting was Joe Britt, who was at 3DO at the time. I left him a voice mail one day, and the office phone rang at three a.m. a few days later. We interviewed Joe at four a.m. and by six he had decided to join. It was a crazy time. Joe is now Founder and VP Engineering at Danger, the makers of the T-Mobile Hiptop.

Sega-16: After the shaky starts of both the Gameline service on the Atari 2600 and the Baton Tele-modem on the NES, was there ever any doubt about whether or not the Xband could succeed? Online gaming was still an unproven concept at the time, and many people believed that modem speeds were not ready for the burden of playing against someone long distance.

Konstantin Othmer: Perlman and Rosko had recruited Adam Grosser who was at Sony to be President and Lynn Heublein who was at gaming company THQ as VP Marketing. There were something like thirty million Sega (Genesis consoles) that had been sold so we certainly figured the market potential was there. Adam and Lynn organized some focus groups where we showed kids the product had unbelievable results. The kids all loved the service, and we could watch (through a two-way mirror) them beg their parents for it. One kid said “Mom, get this for me and I will always do my homework.”

We believed the key to success was making it work with the most popular games. At the time these were Mortal Kombat and NBA Jam. Previous attempts had special “network” games. And that was our secret sauce – figuring out how to make existing games synchronize and play in real-time. We figured if we could cross that technical hurdle, and believe me, that was quite a hurdle, we would have a home run.

Sega-16: The Xband was initially released for the Genesis, and Sega at the time wasn’t afraid of approving some third party projects that Nintendo rejected (like the Game Genie). The company seemed pretty open minded to concepts that pushed the hardware into new territory, given that it was technologically weaker than the SNES. What was its initial reaction towards the Xband?

Konstantin Othmer: Due to the Game Genie and the Supreme Court case that made the Game Genie legal, we knew we could launch with or without Sega’s approval. When we showed it to them, they were very supportive and eventually invested in the company. We had the same support from Nintendo who even helped us by doing a lot of the work to synchronize their game Killer Instinct themselves. Both companies were impressed with the ability to play games in real time with $24 worth of hardware. Doing those demos was really fun.

Konstantin Othmer: Due to the Game Genie and the Supreme Court case that made the Game Genie legal, we knew we could launch with or without Sega’s approval. When we showed it to them, they were very supportive and eventually invested in the company. We had the same support from Nintendo who even helped us by doing a lot of the work to synchronize their game Killer Instinct themselves. Both companies were impressed with the ability to play games in real time with $24 worth of hardware. Doing those demos was really fun.

Sega-16: Could the modem have been made faster or had more features incorporated, or was the released product as powerful as possible within the price range?

Konstantin Othmer: “Fast” is a tricky word. The key design point for the modem was latency – how long it takes for packets to get from one place to the other. Modems at the time were designed around throughput, ie 2400 baud or 9600 baud. It turns out latency and throughput is not particularly related. Think of motorcycles compared to moving vans. The motor cycles can move a small amount very quickly (low latency) while a moving van can move a lot of stuff but it takes longer to get there. We were most interested in latency during game play so games like Mortal Kombat could play in real time.

The modem we used was actually 2400 baud, but we put it in a special mode where we were actually controlling the modem at a much lower level. The default behavior of modems is to compress the data (which increases throughput but also increases latency) something we didn’t want. For a local call we could run two systems at two frames of latency (about thirty-six milliseconds) and we were at three frames across the country. Almost all the gamers we ever talked to thought it was just as though people were playing on the same system at two frames, and at three frames they could tell something was a little different, but didn’t know what it was and didn’t complain about the play. They just knew the game was doing something different.

The bottom line: we think we hit our design goal of making off the shelf games play in real-time.

As far as other features go, we pretty much put everything in the product we could imagine. We had up to four users per device (even computers at the time were not multi-user), we had an address book that was backed up to the network (so if you had to replace your modem, all your data came back), we had ratings based on who you beat, we had online news, high score rankings, and tournaments. We let you pick your own player icon, and you could send us a picture and get your own custom icon. We even synchronized all your data with every other player that had you on their player list. We were very surprised how this was used: people would update their own player info as a type of newsletter, and then everyone else could automatically see that when they logged on and then looked at your info in the contact list.

We supported email and a keyboard. The XBAND was by far the lowest cost email device at the time, though we never marketed it that way. We supported a feature called XBAND Nationwide, where you could place discount phone calls to people across the country. Finally, we supported smart cards which were eventually used by Blockbuster to rent the units.

As I mentioned, we started April 1st and had to be done by September to leave enough time for manufacturing and distribution to make the holidays. We were lucky to have such a talented team, everyone one of which worked as close to 24×7 as possible. Andy Fadden would work forty hours straight and then sleep for fourteen hours. I was on a twenty-six hour day so would slowly rotate around the clock. It was a crazy time. Looking back, it doesn’t really seem possible to build the whole system in that time frame. When we first demoed in public a reporter asked when we started, and when I told him “April,” he asked if that was April 1992. When I told him it was a few months ago, he refused to believe me. The team was fantastic.

I think we pretty much had every feature in 1994 that the XBOX Live and the Playstation Network have today. One feature we thought about putting in that never made it was game genie like functionality. This would allow you to use the system as a single player and download various hacks to games. I’m not sure what more we could have done, and I’m still puzzled why we didn’t have more success. Our timing was not great – we were at the end of the 16-bit systems lifetime, but we also had products on the Saturn which didn’t do well either. I think we may have been a decade early.

Sega-16: The actual unit was sold quite inexpensively ($20). Would it have been possible to have implemented a toll-free number for play? Would this have affected Catapult’s profits?

Konstantin Othmer: At $20, we were losing money on the hardware. This is similar to the model the mobile phone carriers use today. They subsidize the phone in exchange for a two-year contract. The idea behind our network was that there would be minimum calling charges. You dialed into a local X.25 network and the network either put your modem in a state waiting for someone else to call you, or dialed another waiting person in your local area. For busy markets, the wait time during peak hours was usually just a few minutes. The advantage of the direct local call is that it’s free and it enables real-time play. Had we gone through the X.25 network or the Internet, you could not have played games like Mortal Kombat or NBA Jam.

The problem with this network topology is that you need critical mass in your local area playing the game you want to play. This is why we launched in just five markets: LA, New York, San Francisco, Chicago, and Atlanta. Eventually we added Kansas City which happened to have a very large local calling area. We also introduced XBAND Nationwide which was something like $3.50 per hour to play people anywhere in the country. We charged both sides as the cost of long distance calls in the mid ’90s was still really high. Our goal with XBAND Nationwide was to improve the experience and we were providing the service at essentially what it cost us. But for most people that is very expensive.

Sega-16: Do you think more could have been done against those who dropped out of a game early due to losing? It’s a problem that still affects many online games.

Konstantin Othmer: We worked on that problem extensively and I think we eventually plugged most of the holes. Andy Fadden has a great write-up on his website that talks about this issue in great detail. It turned out to be a problem, sort of like spam and viruses. We refined our techniques here for quite some time and eventually had a very sophisticated system to resolve issues when people cheated this way. I think we solved this one pretty well, and we ended up running some tournaments and had high score lists which reflected the best players.

Sega-16: Were there any features pending that didn’t make it in before the Xband was discontinued?

Sega-16: Were there any features pending that didn’t make it in before the Xband was discontinued?

Konstantin Othmer: The next things on our list were web browsing and game-genie like features. I don’t think features were the issue, but would love to hear any thoughts on that front. I’m still puzzled why we didn’t have more success.

It’s interesting; the people who used the service were fanatical. We had people who played 80 hours per week! They loved it, and there are still people talking about it today. Last year I got a bunch of emails from a group trying to revive the service! How many technology products that failed do you know that still have a following thirteen years later? It’s a dubious distinction, I guess, but it points to the following we had. Unfortunately, we never “crossed the chasm” to the main stream market.

Sega-16: On which console did the Xband run smoother, the Genesis or the SNES?

Konstantin Othmer: I think they were equivalent. We had the ability to upgrade the modem and made frequent updates to fix things. So even though the Nintendo version came a few months after the Sega, we kept the feature set and software quality at parity.

Sega-16: Which console had better sales?

Konstantin Othmer: I don’t remember – I think they were about equivalent.

Sega-16: Did you leave Catapult before or after it merged with MPath? What was it like there at the end?

Konstantin Othmer: The “end” was as crazy as the rest of the time. There was an engineering walk-out, a 30 page manifesto, and a bunch of calls to 911. I did stay through the acquisition but left shortly afterward when my role changed.

Sega-16: Why do you think the Xband wasn’t as successful as it could have been? Was it solely the Internet explosion, or do you think there were other factors involved?

Konstantin Othmer: I think there were combinations of factors. A number that contributed: Parents don’t want their phone lines tied up, marketing of on-line services was not well understood at the time, particularly that up front HW costs need to be subsidized; the importance of try-before-you-buy and having a low-cost way to sample the service, and finally the general understanding of online services and the Internet at the time. All that said, I’m still a bit puzzled. I can’t explain why Tivo has not been more successful either.

Sega-16: The Xband was the first true step forward online console gaming and a precursor to SegaNet, Xbox Live, and now the Playstation Network. How does it make you feel to have been part of such an important part of gaming history?

Konstantin Othmer: I have no idea how to answer that. It was a crazy time – I sure wish we would have had market success. I’m still in touch with most of the people who were at Catapult. So much outrageous stuff happened; we always have fun reminiscing when we get together.

Sega-16 would like to thank Mr. Othmer for his time and all the great information he provided about the Xband.

Recent Comments