Long before Sega’s growth in the early ’90s, there was a small but dedicated team of people who were hard at work to make its arcade division – already established in the U.S. – a success. The company was on fire during this period, pumping out one classic after another, and it was this success that became the foundation for much of the Master System, later the Genesis, library.

Long before Sega’s growth in the early ’90s, there was a small but dedicated team of people who were hard at work to make its arcade division – already established in the U.S. – a success. The company was on fire during this period, pumping out one classic after another, and it was this success that became the foundation for much of the Master System, later the Genesis, library.

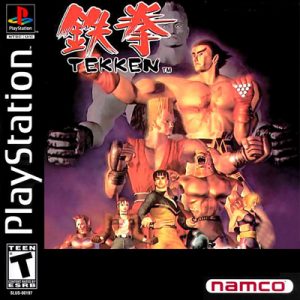

Jerry Momoda was a very important and active member of Sega’s team at this time. During his time in the industry, Momoda has been fortunate to work at some of the most influential game companies at times when they were either dominating the market or pushing hardware boundaries. With a résumé that includes Nintendo, Atari, and Namco, he was a major force behind the western release of Sega arcade hits like OutRun and Hang-On, as well as Stun Runner for Atari and Tekken at Namco. Though his work was in the arcade division of these companies, it often had a direct impact on the consoles of the time, including Sega’s.

Sega-16 recently spoke to Mr. Momoda about his work at Sega and in the game industry.

Sega-16: You were one of the first 10 employees hired at Nintendo of America. How did you initially start there? Were you specifically looking to get into the video game industry?

Jerry Momoda: I thought it would be cool, but had no idea how to. I didn’t even know NOA was near where I lived. Donkey Kong happened to be my favorite game at the time. While becoming a pretty good player, I observed the game for more than simply high scores. I shared some insights during a chance meeting with Ron Judy/NOA VP Marketing. This led to a meeting with Minoru Arakawa/NOA president and a follow demonstration for employees the next day. I wrote a blog post about this entitled, “Nintendo: My First Video Game Job.”

Sega-16: Other employees, like Howard Phillips, often talk about how uncertain the company’s future in America was back then. Nintendo was certainly doing well in arcades, but did you think those titles could do as well on a home console?

Jerry Momoda: At that time, and in that market, no one could have honestly foreseen how the NES would turn around the market. The coin-op market was reaching a saturation point, and the Atari debacle created zero confidence in the console market.

There was enough data to forecast which games had the best chance to succeed here. Nintendo of America (NOA) could draw from each game’s Famicom (Japan) performance and how it did as a coin-op game (N. America). Without this market information, launching the NES would have been a total crap-shoot. Ironically, the failure of Atari’s console game ultimately would help propel the NES. Though not as robust as coin-op, NES games were without question superior to Atari’s.

It’s important to note that when the NES launched, there was a widening technology disparity between coin-op and console games. And while many NES games became hits, their initial coin-op performance was in many cases average at best. But compared to the lower quality Atari console games, the first party NES games provided consumers much needed confidence. The Vs. System was like a Trojan horse that primed the market for the NES’ launch in 1985.

Sega-16: You left Nintendo in 1985 to join Sega, just as the NES was hitting store shelves. What made you decide to leave?

Jerry Momoda: My goal was to become more involved with game development. I wanted the opportunity to visit NCL and become more acquainted with game development. I wasn’t patient enough, and with the opportunity to become the Sega product manager and move to sunny California, I took that leap.

Was it the right move, or do I regret it? Yes and no. The Sega job was a disappointment, but to later work for Atari Games was a dream come true. That led to a job at Namco where I helped spearhead significant games at a very pivotal time in the company’s history.

Sega-16: In the mid ‘80s, Sega Enterprises operated out of an office in San Jose, California and bringing over a steady stream of arcade hits. What was it like to work in that environment?

Jerry Momoda: The office in San Jose was small and manufacturing was contracted out. We had a good run of games, but their R&D was more isolated and less collaborative than Nintendo. Others have shared that opinion about Sega, and I believe that philosophy has hurt the company in the long run.

Sega-16: As product manager, you were involved in the localization of some of Sega’s most beloved classics, like Hang-On, OutRun, and Choplifter. Were there any that almost didn’t make it out of Japan or were all of them intended for a western release?

Jerry Momoda: As a subsidiary of the parent company, any game that might have potential in Nintendo of America was sent here for testing. Most of the games sold in this market were of the “low-hanging fruit” variety. Proven genre like driving, flying and shooting were proven in this market. Games like Atari’s Gauntlet inspired four-player coin drop games like Quartet.

Sega-16: It’s fascinating to hear Sega being inspired by Atari. Do you recall any other discussion about other companies’ games influencing Sega’s?

Jerry Momoda: No discussions, only my assumptions. Some are obvious. Mario influenced the creation of Sonic. Atari’s Gauntlet was released in 1985, and Quartet followed in 1986. In 1988, Sega introduced Hot Rod. You could draw similarities to Atari’s top down driver, Indy 4 and Indy 800.

Jerry Momoda: No discussions, only my assumptions. Some are obvious. Mario influenced the creation of Sonic. Atari’s Gauntlet was released in 1985, and Quartet followed in 1986. In 1988, Sega introduced Hot Rod. You could draw similarities to Atari’s top down driver, Indy 4 and Indy 800.

Sega-16: How did Sega determine which arcade titles to bring to the West? Was this done by the U.S. office or was it decided in Japan?

Jerry Momoda: Sega devoted more resources to titles that had the best opportunity for global success, so in a way, you could say many were pre-determined by Sega Japan. It becomes clear which games are suited for international vs. domestic markets. Naturally, Sega Japan wanted us to take more titles than we wanted to sell. Some were clearly not for our market, but we had to test them to prove it.

Sega-16: Many of those arcade titles later ported to the Master System. Do you recall if there was ever any collaboration with Sega of America or were the games done separately?

Jerry Momoda: Steve Hanawa, who earlier worked for Sega Japan, collaborated with the console division on early Master System games.

Sega-16: You said earlier that your time at Sega was a disappointment. Was it a corporate problem, or were you dissatisfied with the technology?

Jerry Momoda: It was purely a corporate thing. I left Nintendo because I wanted to pursue more cutting edge games, visit NCL and ultimately become more involved in game development. At Sega, I was disappointed upon realizing I wouldn’t achieve my goals there, but I had the opportunity to learn more about the sales side of the business. In the process I realized design and development were my strengths and passion. So, I joined SNK, immediately went to Japan and started working with a great team, but just six months into the job, Atari came knocking.

Sega-16: Many former Sega of America people have commented on their experiences working with Sega of Japan, but it’s interesting to hear it from someone in the arcade division. Was there every any friction with Sega of Japan about which games to test or localize?

Jerry Momoda: For me, no friction. In Sega’s case, there wasn’t a free flow of R&D information. Sega was a dominant coin-op developer with years of experience. They made wonderful games and did things their way.

When looking back to experiences with other Japanese companies, Sega’s culture was less collaborative. The Japanese domestic market and the American market are unique to one another. The differences range from what games are popular, where and how they’re played, to the people who play them. Back in the day without the web, finding information about games and players wasn’t easy. You had to talk to people. I conducted my own research and often had to trust my instincts. Distributors would ask me which games to buy.

Sega-16: Sega and Namco have often been viewed as arcade rivals. Did you ever see this while working at either company? Was there a feeling that one had to outdo the other specifically?

Jerry Momoda: Yes. Both company presidents, Nakayama (Sega) and Nakamura (Namco), are fiercely competitive and proud men. Each have an important role in the history of video games. Their companies are in many ways a reflection of the men themselves. I believe Sega was perhaps a better technology innovator, while Namco was more creative and collaborative.

Sega-16: After Sega, you worked at Atari and launched hits like Cyberball, Pit Fighter, and Stun Runner. How was the environment there? It was no longer the Atari of old, but it was still a strong arcade competitor.

Jerry Momoda: I joined the marketing team led by Mary Fujihara in 1987. Marketing and engineering shared different views of the road ahead. Atari became challenged within a changing market and veteran personnel began to depart. Atari was behind in 3D coin-op hardware development and trending game genre. A resistance to the fighting game genre earned me the nickname “blood and guts Momoda.” And for decisions with regards to Nintendo, they would cost the company dearly. Even so, Atari remained competitive long after their prime. Working there was a dream come true. Atari’s influence on the history of gaming is immeasurable. I have great respect for the company, it’s people and history.

Sega-16: Given Atari’s position in the market during your tenure and the difficulties it had adapting to changing trends, do you recall any games the company passed on that might have been successful in the market at the time?

Jerry Momoda: Some that had potential were, Blazer, Metal Hawk, Phelios, and Rolling Thunder II. We tested a lot of Namco games, but naturally we couldn’t sell them all. There was internal products to sell, also. Atari also had to be concerned with market cannibalization. Marketing two games of the same genre, at near the same time resulted in lower total sales. As a licensee, we were obligated to sell a certain number of titles each year. Management had to juggle a dynamic internal development schedule while upholding commitments to represent Namco’s games. Namco games were really valuable during lean times, when internal projects didn’t pan out.

Sega-16: You were instrumental in the development of Namco’s Tekken series and saw its transition into a major publisher for the Playstation. Did it seem to you at the time that arcades were in danger of being supplanted by home consoles once and for all?

Jerry Momoda: Most definitely. In my blog, I wrote a post titled Namco: The Role of Coin-op in the PlayStation. Before the PlayStation, coin-op and console industries were able to co-exist. Coin-op remained superior because each game could utilize the latest and greatest technology.

During the early development of Tekken, I learned of the partnership between Namco and Sony regarding the System 11 hardware. Any apprehension was set aside because Sony was new to console gaming, and console conversions of arcade games were historically inferior. This partnership provided us an early look at Ridge Racer for the PlayStation. My jaw dropped at its near perfect conversion. It wasn’t long before coin-op releases became marketing tools for console releases.

During the early development of Tekken, I learned of the partnership between Namco and Sony regarding the System 11 hardware. Any apprehension was set aside because Sony was new to console gaming, and console conversions of arcade games were historically inferior. This partnership provided us an early look at Ridge Racer for the PlayStation. My jaw dropped at its near perfect conversion. It wasn’t long before coin-op releases became marketing tools for console releases.

Initially, there was a six month window to allow game operators time to earn a return on investment before the home release. But that window quickly closed to a just few weeks. To a consumer’s eye, it became difficult to distinguish a negligible difference between arcade and console games. The writing was on the wall. In big, bold letters.

Sega-16: I read your blog post on Namco and the PlayStation. Fascinating stuff! It seemed like Namco underestimated the effect the PlayStation would have on arcades. More than just being games in development, innovative titles like Prop Cycle and Time Crisis were direct responses to the need to separate arcades from consoles and emphasize the unique experience arcades provided, correct?

Jerry Momoda: At least not to the full extent. In Namco’s defense, no previous console had delivered a knockout blow to coin-op, and until the PlayStation, Sony was not a real threat in gaming. Since Namco was working closely with Sony, they realized what loomed ahead before I did.

After the PlayStation’s introduction, coin-op was forced to pivot. We were chartered with the task of creating game experiences that would bring players back to arcades. I conceived of a gun game that contributed to the design of Time Crisis. One of the unsung heroes of that era was Prop Cycle. It was so innovative and perfectly executed on our mission. Hopefully Namco resurrects this title, as it would make an incredible VR experience.

Sega-16: What do you think of the resurgence in popularity of classic arcade games? Sega’s 3D Classics series on the Nintendo 3DS is phenomenal, and Atari and Nintendo’s arcade hits continue to be in demand with gamers of all ages.

Jerry Momoda: I think it’s great that young players have an appreciation for classic arcade games. Games like Flappy Bird and Crossy Road were hits because they took many cues from classic coin-op games. I wish players today could experience the classics in their dedicated cabinets, using classic game controls. I feel very fortunate to have been a part of the classic game era. All game developers have something to learn from classic arcade games.

Our thanks to Mr. Momoda for taking the time for this interview!

Hang-On image property of OutRun ’86. All other images are property of Jerry Momoda.

Recent Comments