Nowadays, it seems like the name Electronic Arts is practically synonymous with video games. Say what you will about its current business practices, you cannot deny that it’s done everything needed for a company to dominate the industry. This is something that has been  EA’s mantra since day one. Releasing the best product possible and taking maximum advantage of available hardware was what made Electronic Arts one of the brightest stars in the Genesis licensing sky.

EA’s mantra since day one. Releasing the best product possible and taking maximum advantage of available hardware was what made Electronic Arts one of the brightest stars in the Genesis licensing sky.

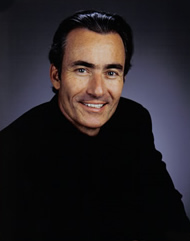

All of this was started in 1982 by Trip Hawkins. A graduate of both Harvard College and Stanford University, Hawkins has been at the forefront of the gaming industry almost since its inception, and he’s only getting started. After starting at Apple, where he played a critical role in the establishment of the personal computer, he founded Electronic Arts and turned it into a 3rd party juggernaut. Later, he set the groundwork for the 32-bit generation with the 3DO and now runs Digital Chocolate, a leader in games and applications for mobile phones.

Sega-16 recently had the pleasure of talking with Mr. Hawkins about Electronic Arts’ penchant for giving the Genesis some if its most memorable games, as well as its role in making the console such a success.

Sega-16: Some publishers complained about Sega attempting to emulate the strict licensing policies Nintendo had. Was this ever the case with EA?

Trip Hawkins: Sega’s initial “standard license agreement” was indeed a Nintendo clone. EA skirted this because we reverse engineered the Genesis and therefore did not technically need a license agreement to bring games to market. This gave me a lot of leverage in negotiating a reasonable license, which I did in 1990.

Sega-16: According to Steven Kent’s Ultimate History of Video Games, you had a certain “disdain” for consoles, and refused to publish for the NES because you would have had to tone down your games for the hardware. The Genesis, however, was much better suited for PC ports. How long did it take you to recognize that the 16-bit console market was worth getting into?

Trip Hawkins: Other than Acclaim, all the American publishers avoided the 8-bit Nintendo and had disdain for their model. None of us at that time appreciated how license fees could be used to subsidize hardware pricing and marketing, and thereby help companies like Nintendo build an installed base.

Also, the 8-bit systems were pretty limited, but then I heard about the 16-bit Sega plans. With the Genesis, I was probably the first American to “get it.” I had a lot of personal experience with the Motorola MC-68000 processor. We’d used it in the Lisa and the Mac at Apple. EA bought Sun workstations that used it. We ported Marble Madness from a coin-op machine that used it. It was in the Amiga and the Atari ST. In fact we had a good library of technologies and products that ran on the 68000. So I was very excited when I heard about the Fall 1988 debut of the Sega Mega Drive in Japan, which would come to the US in the Fall of 1989 as the Sega Genesis. I had one of our guys buy one in Japan very quickly so we could study it. I loved the idea of a solid 68000-based machine for under $200. Within weeks I had decided we should have an aggressive strategy to support it via a reverse engineering strategy so we would not need a license. We released our first Genesis games in June, 1990. I am not exaggerating, but it literally took three years for any other major third parties to show up with any kind of reasonable commitment of products for the Genesis. As a result, EA and Sega divided up most of the market.

Sega-16: It seems like you were going to develop for the Genesis, regardless of whether Sega licensed you or not. What was Sega’s initial reaction when you approached it about developing software and showed that you had reverse-engineered its new hardware?

Trip Hawkins: They huffed and puffed and said they would blow my house down. When intimidation did not work, we got down to brass tacks and they accepted that I was committed to going to market with or without a license. They became much more reasonable after that because they were afraid I would hurt their third party program by licensing my information to competitors.

Sega-16: Electronic Arts’ attention to game packaging was one of the things that distinguished it from other PC publishers. Still, many gamers question why you choose to use cardboard game boxes when most other Genesis titles were sold in clamshell cases. Were the clamshells ever an option?

Trip Hawkins: I don’t recall precisely, but I suspect that we had lower costs for the cardboard boxes and thought that the clamshells were tacky.

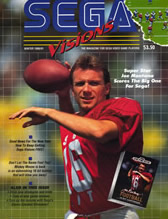

Sega-16: It’s a little known fact that the original Joe Montana Football was designed by Electronic Arts, due to Mediagenic’s failure to produce a finished product by November, 1990. Most people never think to associate the game with EA due to its sharp contrasts with the Madden series. Did Sega ever question the more arcadey style of Joe Montana, with its fewer teams and smaller playbook, or were they just glad to have a finished game for the holidays?

Sega-16: It’s a little known fact that the original Joe Montana Football was designed by Electronic Arts, due to Mediagenic’s failure to produce a finished product by November, 1990. Most people never think to associate the game with EA due to its sharp contrasts with the Madden series. Did Sega ever question the more arcadey style of Joe Montana, with its fewer teams and smaller playbook, or were they just glad to have a finished game for the holidays?

Trip Hawkins: I made the decision to help them, proposed the deal structure, and dictated the design. I even diagrammed all the plays in the playbook for Montana. I was all over it because I wanted to make sure Sega was happy with something that I knew would not hurt Madden. They had no problem with the proposed look and feel because that style worked in Japan. They were very happy. We were very happy because we built Montana in six weeks and were paid $2 million for out of pocket costs of about $20,000. Both games were in the Top 5 that Christmas.

Sega-16: Were you ever contacted to do another installment?

Trip Hawkins: No, neither side really wanted to have to do it again.

Sega-16: Tom Kalinske recently stated that the Genesis helped put EA “on the map to some degree.” Would you agree with this assessment? It obviously goes both ways though. How big a part in the Genesis’ success do you think EA had?

Trip Hawkins: EA had been the #1 computer game company for five years in a row before the Genesis came along, so I think EA would have succeeded in the long-run with or without the Genesis. But the Genesis did come along, and because the risky reverse-engineering strategy paid off, it did catapult EA forward, especially for EA Sports.

Sega-16: There’s been some measure of controversy over whether or not EA had a preference for the Genesis over the SNES. Some people have even gone so far as to say that the SNES received inferior ports of Madden and NHL Hockey, as well as other titles. Is there any truth to this? Was the Genesis ever given preferential treatment, or were both consoles treated equally?

Trip Hawkins: EA certainly did the best job it could for both machines, but the Genesis was in the market two years earlier so the software engines had a big lead. And Nintendo was trying, and failing, to achieve backwards-compatibility which forced them to use the inferior 65816 processor. As a result, the Genesis had faster drawing speed, although the SNES had a larger color palette. As a result, the Genesis was a better machine for sports games that did not need the extra colors as much as they needed a good frame rate. Nintendo was better suited for conventional Mario games that were 2D at the time.

Sega-16: Your opinion of the 32X is well documented, yet was there ever a time at EA that developing for it was a consideration?

Trip Hawkins: What people may have a hard time believing is that from 1982-1992 EA considered more than 300 different platforms for games. Most of them were not supported and most of them failed. The 32X was considered because we always considered every possible platform. But it did not have a lot going for it. It was more of a gimmick.

Sega-16: The laundry list of conflicts between the Japanese and American branches of Sega is well known, and this is most likely what cost it the top spot in the industry. EA was going in a different direction at the time with the 3DO and eventual PlayStation support. The 32X and Saturn didn’t receive much support, which was a common theme among 3rd party developers at the time. When did you finally decide it was time to let go of your strong support of Sega and move on? What prompted the decision?

Sega-16: The laundry list of conflicts between the Japanese and American branches of Sega is well known, and this is most likely what cost it the top spot in the industry. EA was going in a different direction at the time with the 3DO and eventual PlayStation support. The 32X and Saturn didn’t receive much support, which was a common theme among 3rd party developers at the time. When did you finally decide it was time to let go of your strong support of Sega and move on? What prompted the decision?

Trip Hawkins: I don’t think conflict between the Sega offices really had anything to do with EA’s support. When it came down to it, EA threw its full support to Saturn but Sony just beat Saturn in the marketplace. Even Nintendo privately told me that they had never seen anything like the brand power of Sony.

Sega-16 would like to thank Mr. Hawkins for his time.

Pingback: A história do Mega Drive - parte 2 - Memória BIT