Anyone under the age of 30 probably knows Sega from its releases on current consoles, as well as the looming presence of Sonic the Hedgehog in everything retail. People a bit older are familiar with company’s console history, and those with more than a few grey hairs remember how Sega once dominated arcades. But when you mention Sega pinball to arcade fans, those who know are quick to bring up the slew of licensed tables that were released between 1994 and 1999 under the seasoned leadership of Gary Stern and licensing expert Joe Kaminkow. But – to steal a line from The Matrix – what if I told you that Sega started making pinball tables more than two decades before Stern had the helm?

Yes, the Stern/Kaminkow run was actually Sega’s second direct attempt at taming the silver ball (a peripheral attempt in Europe will be discussed in part two of this series). The first try is likely only remembered by those already retired, and even then, only by people familiar with the Japanese coin-op scene. Long before consoles and even before it launched its arcade video game business with Pong-Tron, Sega spent a few years producing pinball tables in Japan.

Insert Coin to Start

First, we need to provide a bit of context. Sega didn’t enter the game business with consoles, having already been making electro-mechanical games for more than 20 years and arcade video games for a decade when the SG-1000 debuted in Japan. To fully understand how and why Sega started making pinball machines, as well as why it eventually quit, we must look at where the company – and the country of Japan – were at the time.

Let’s start with Japan. After World War II, the country was just getting back on its feet economically. Citizens didn’t have a lot of disposable income, so coin-operated (coin-op) amusement machines saw American military bases as their first stop when entering Japan. Future video game titans like Taito and Sega grew steadily in the 1950s thanks to the coin-op business. Vending machines, jukeboxes (Taito), and phone booths (Rosen Enterprises) were among the most popular coin-op technology on the island nation.

Technologically, Japanese coin-op amusement machines in the 1950s were still years behind those made in the U.S., and pinball wasn’t yet ready to become a major business. Pachinko, a game where players launch small balls into a playfield that then bounce through pins to hopefully land in pockets that award more balls that can be exchanged for prizes, was the dominant ball-centered game in Japan. It had gone dormant during the war but was now back in style thanks to a lack of affordable entertainment and easily-obtainable building materials.

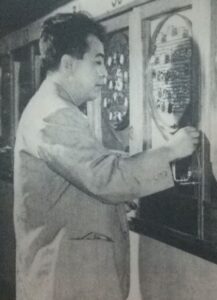

At this time, there weren’t specific game centers in Japan. Some locations had selections of light gun games in what were called “gun corners.” Sega was in that business with locations in Tokyo and Osaka, importing pinball and gun games made by Midway Manufacturing. Most of the machines were second-hand and were often problematic. “Being used, they broke down a lot. The maintenance was terrible. Partly for that reason, we decided to manufacture guns and flippers ourselves in Japan, which led us to start developing our own arcade games,” recalled former Sega director Akira Nagai. The unreliability of the used games it was importing prompted Sega to move towards developing its own coin-op games.

Even so, Sega Japanese pinball design would need more time to mature. As Nagai stated, Sega’s focus was changing during the 1960s away from distributing games made by other companies. In 1967, Sega Chairman David Rosen felt that the coin-op industry was suffering from a glut of me-too games and wasn’t innovative enough. Aside from minor cosmetic changes, they were too similar. He wanted Sega to create original products to that could be manufactured in or exported to the U.S. Rosen believed that such a move wasn’t just important for Sega’s survival but for that of the industry as a whole. At this point, Sega still couldn’t make and distribute its own games in the U.S. and relied on licensing agreements with American companies like Bally Manufacturing. Among the first games produced was 1966’s Basketball. With such agreements, Rosen wanted it to be clear that Sega wasn’t trying to compete with major American manufacturers but rather complement them. “The design criterion for equipment destined for overseas is to produce units with strong player appeal that are too expensive to engineer and make in limited quantities in the U.S. or Europe,” he told Cash Box magazine in 1968. Rosen also mentioned that Sega had become Japan’s largest manufacturer, distributor, importer, exporter, and operator of coin-op machines, shipping games to over 30 countries worldwide.

With these exports, Sega had begun taking steps to penetrate the U.S. amusement market. At the 1968 Music Operators Association (MOA) Trade Show, it announced a licensing deal with Williams Electronics, a division of the automated musical giant Seeburg Corporation, to distribute low-cost games in the U.S. Sega planned to introduce five new Japanese-made games a year, starting with Basketball, Punching Bag, and Rifleman early the next year. By 1968, Sega had at least 12 games under development to be released according to market demand, plant capacity, and other factors. Its Research and Development and Engineering Production departments grew to over 80 employees. These early successes would lead to major hits like Periscope I (1968) and Missile (c. 1969), fundamentally changing the company and putting it more at the helm of its own destiny in North America. Moreover, the deal with Williams would plant a seed that Sega would try to grow in a few short years by trying to buy the pinball maker from Seeburg to increase its North American footprint.

Sega Plunges into Pinball

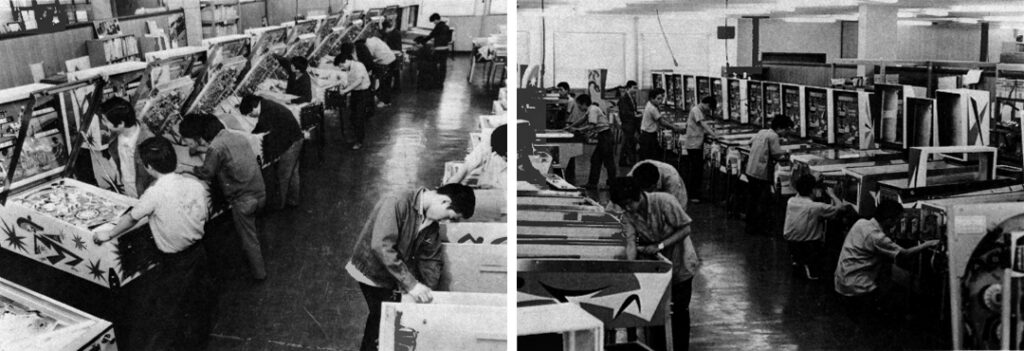

Pachinko was big business in Japan, but there was one major difference between it and pinball that permitted the latter to remain viable in Japan, as described by former Sega executive Masuharu Yoshii, an electrical engineering graduate from Nihon University who got his start at the company in 1970 doing metal and sheet processing. “Pinball and pachinko belonged to entirely different categories,” he told the author. “Pinball was considered an arcade game, whereas pachinko was a form of gambling. As a result, minors under the age of 20 were not allowed to play pachinko. On the other hand, pinball was a type of arcade game, so anyone could play, regardless of age. For these reasons, pinball did have a decent level of popularity.” Yoshii was among the first people hired by the new Sega Enterprises after Nihon Goraku Bussan acquired Rosen Enterprises Ltd. in July 1965 and changed its name. He joined alongside Hideki Sato and spent two years in Sega’s Production and Engineering Department, run by Shikanosuke Ochi. There, Yoshii honed his craft programming Sega’s electromechanical games before finally graduating to pinball. The whole operation was still quite small, consisting of only 20 employees. At first, development was a unified affair, with employees divided into two groups, the factory workers and the researchers. These researchers drew up the blueprints that were then sent to the factory for manufacture. This process was used for all Sega’s electromechanical products. “The factory workers would use lathes and other tools to shape metal or wood parts according to the blueprints and then deliver the finished parts,” explained Sato in a 2021 interview for the Sega Hard Historia book. “After that, we’d use calipers [an instrument used to measure the length, width, thickness, diameter or depth of an object or hole] and other measuring tools to check whether the parts matched the drawings precisely. Once confirmed, we would proceed to assemble the product.” By Sato’s second year at Sega, the structure was changed; researchers became managers, and development was organized into individual teams of two or three people who worked on electromechanical games or slot machines. The pinball team started with only three people (including Sato) but eventually grew slightly larger, capping at around seven members. Sega’s pinball operation was small, so rather than having multiple projects running in parallel, one team focused on developing a single game at a time.

Typically, Sega’s pinball team consisted of a project leader who was responsible for the game’s name, features, and playfield layout. One or two artists did the backglass and playfield art, while two or three mechanical engineers set up bumpers and ball-control mechanisms on the playfield and wired them for operation. Lastly, there was the programmer, who designed and prototyped circuits for new mechanisms and then coded them in. The ideas for game design came from people outside the pinball team, in large part from Ochi himself. Ochi was one of Sega’s most prolific and talented minds. He was likely involved with Periscope, and during his time at Sega, he would patent multiple designs for games like Bullet Mark and the first laserdisc title, Astron Belt. “Ochi-san was in charge of planning not only for pinball, but for all of Sega’s arcade games,” Yoshii explained. “While he left the finer details to the individual staff members, I believe the original ideas all came from him. First, he would create a rough concept, then pass it down to his subordinates, who would flesh it out into a proposal. That proposal would then come to me.” Yoshii would sometimes find ideas too difficult to implement and make changes on his own. The team would then manufacture a sample machine, or whitewood (a preliminary, unadorned version of the pinball machine’s playfield), to implement concepts. Sega put a lot of effort into making each of its pinball machines different from American ones. The focus was on speed, something Sega’s pinball team felt would contrast with U.S. models, which were considered slow. “We used electromagnets and other mechanisms to make the ball movements more dynamic. We added lots of features like 50-point or 100-point bonuses, like a pachinko machine, to make the games more exciting,” Sato detailed. If a game didn’t seem fun, members held an internal company tournament of about a dozen employees to compete and offer suggestions. “It wasn’t just about building the machine. We’d play it together, experiment with things like where to place the ball-holding areas or try releasing the ball in three different directions. We spent the most time refining the fun aspect of the game,” said Sato. Once finalized, the machine was put into production.

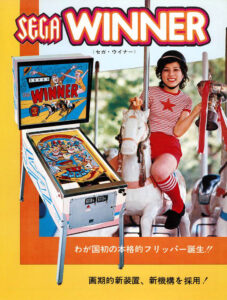

Sega made good use of the time and knowledge it gained making original electromechanical games for more than just R&D, and the time for pinball would finally come in 1971, 12 years before its first game console and while it was still a subsidiary of Gulf + Western Industries, owner of Paramount Pictures. Sega spent three years researching and engineering its first pinball machine, Winner, a table that Rosen proudly presented at a series of parties to distributors and operators in August of 1971. As an electromechanical table, Winner was designed to require minimum service. For instance, whereas the playfields on U.S.-made pinball machines were accessed by sliding the cover glass completely out, a process that was inconvenient and occasionally even dangerous, the glass on Sega’s tables easily raised up. Additionally, Sega’s relays were packed inside a plastic box within the machine to protect them, while the relays in U.S. tables were exposed. Sega touted the game’s other innovations, like microswitch bumpers and its use of mostly printed wiring to avoid short circuits and broken wires. For the moment, Sega had no plans to sell Winner overseas, and honestly, making pinball for only Japan was a smart move. Most of the tables sold in the country were made in the U.S. and were expensive. A play on one of them cost 50 yen, a price too steep for most Japanese players at the time. Sega’s pinball machines, on the other hand, were only 30 yen.

Over the next few years, Sega released a score of original titles, typically one every three or four months, along with licensed electromechanical pin games, giving them top billing at its numerous game centers across Japan. While some tables were licensed for current events, like 1972’s Sapporo, which was a tie-in for the 1972 Winter Olympics in Sapporo, Japan, most of the licensed tables that Sega released came courtesy of Williams Electronics. Quite a few of them were designed by people who would go on to be regarded as legends in the industry. Doodle Bug (1971) was done by Norm Clark, and two popular tables, Skylab (1974) and Liberty Bell (1976), were designed by Steve Kordek. Another game, Flash, was the work of Steve Ritchie, who is widely known as the “Master of Flow” because his designs emphasize speed and long shots (that table set record on location tests before release). These popular tables, designed by established creators, helped add credibility and variety to Sega’s original tables.

Sega’s start to its pinball business was quick, but it was meant to grow rapidly. And what better way to do so than by absorbing an existing pinball maker? That was Sega’s thinking in 1975 when it moved to acquire Williams Electronics from Seeburg Corporation. Sega wished to expand its North American production and considered Williams’ well-placed facilities a valuable resource for East Coast distribution. It saw a viable partner in Seeburg, which was having serious financial issues and wanted out of the pinball business. The company had tried to update Williams’ image by changing its name to Williams Electronics Inc., but in 1974 it reached a deal in principle to sell the pinball maker to Sega Enterprises. Seeburg would receive 20 percent ownership in the new Sega/Williams company, a $2.25 million loan, and Gulf + Western’s entire stake in Class A Seeburg stock. In return, Sega would take on Williams’ debt and $7 million of Seeburg’s debt. The agreement would have allowed Seeburg to exit the pinball industry while retaining other assets like its vending and slot machine divisions, though a lot of its debt remained.

The backdrop to Seeburg’s troubles was an overall decline in jukebox sales, compounded by Wurlitzer’s withdrawal from the market in 1973, which created a flood of dumped product and damaged the chances for Seeburg’s sales. Although there were seemingly positive developments for the pinball industry in the pipeline – like the lifting of bans in major cities like Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago – Seeburg still considered pinball a non-core component of its company. Court decisions, such as the California Supreme Court’s 1974 ruling that pinball was a game of skill, reversed decades-old prohibitions. In New York, highly publicized events such as author Roger Sharpe’s presentation of pinball as a game of skill to city authorities (but mostly the promise of tremendous tax revenues) rendered legalization appealing. These developments heralded growing business prospects in pinball, but Seeburg didn’t appear keen to capitalize on them.

Instead, the firm was more focused on surviving. Years of growth had stretched Seeburg beyond its depth, and management viewed the sale of the pinball business as an acceptable way of gaining control over its obligations. Even while negotiating with Sega, Seeburg considered offers from other companies, including Taito. It looked like the deal would go through, but only four months later, in a shocking turnabout, Seeburg reversed itself. Chairman Louis Nicastro stated that Seeburg had secured $5.25 million of financing for its Chicago coin-op photograph and vending machine businesses, an additional $2.65 million loan from its major lender, and commitments from 10 independent distributors to place $10 million of firm orders and help retire the loan. These developments stabilized Seeburg’s near-term finances and led to the cancellation of the Sega purchase.

Sega Forges Ahead Alone

Seeburg’s cancellation of the Williams deal left Sega without the major pinball expansion it wanted in the U.S. In Japan, however, it continued to manufacture original and licensed tables. Sega’s time developing electromechanical machines was brief, spanning only three years from Winner in 1971 to Galaxy in 1973. It spent the next few years relying on licensed tables from Williams, but it returned to original designs in 1976 with Rodeo and Big Together. Along with another new table, Temptation, these machines showcased Sega’s transition from the traditional electromechanical systems into solid-state technology.

Throughout the rest of the decade, Sega maintained a presence in pinball, increasing its profile with events like the 1976 “National Flipper Tournament” that took place across Japan during the month of April. Sega ran the competition to coincide with the release of the rock opera movie Tommy, as well as the debut of its newest pinball game, Rodeo. Several high-profile companies sponsored the tournament and provided the prizes, including the Godzilla studio Toho Co., Ltd. Tommy, a trippy pinball-themed film featuring music by the British rock band The Who, told the story of an emotionally troubled young man who becomes a pinball prodigy. The movie had an all-star cast that included Jack Nicholson, Elton John, and Ann Margaret (who won an Oscar for her role). Though not directly tied to any Sega game, Tommy was the highest profile pinball-related film of the time and a perfect vehicle for promotion.

Sega held tournament qualifying rounds at 25 different game centers until April 25th. On that day, players had the chance to reach the regional finals by obtaining the highest score over three balls of play. Over 13,000 people of all ages competed, and the 144 semi-finalists clashed on May 2, 1976, in a half-dozen cities like Tokyo, and Nagoya. The finals were held at Sega’s Tojo Hibuya Game Center in Chiyoda, Tokyo with Godzilla franchise star Haruya Kato interviewing the 16 finalists (most of whom were teenagers). The thrilling finale came after the player order was selected by lottery for one last round on a Rodeo machine. The winner was Teruaki Nakayama, a 17-year-old high school junior, who walked away with a luxury vacation to the U.S. West Coast, while second place took home a new color television.

Rodeo didn’t draw as many crowds as the rest of the competition did, but it was just as big a deal for Sega – big enough for the publisher to declare it first pinball table to use a microprocessor (It wasn’t; 1975’s Spirit of ’76 by Mirco Games of Arizona is commonly cited as the first solid-state pinball table). Despite the misnomer, it was an important step in the company’s pinball evolution from electromechanical systems to solid-state technology. Electromechanical pinball machines relied on switches, solenoids, and relays in controlling scoring and game functions. Although revolutionary for their time, these machines were mechanically weak and constrained, especially with quick action gameplay. Solid-state technology revolutionized all of that, using electronic devices like printed circuit boards (PCBs) and transistors, which cut mechanical complexity dramatically – removing as much as 60 percent of the trouble-prone components – and enabling more reliability and flexibility in design. “These games are essentially controlled sequentially, so we realized that sticking with purely mechanical control wasn’t going to cut it anymore,” Yoshii recalled. “For example, we thought, ‘Why don’t we try spinning the reels of a slot machine using stepper motors?’ Then the question became how to control that, and that’s when we started using CPUs.” After first implementing the technology with its slot machines, Sega soon found applications for it with its pinball tables.

Both Rodeo and Big Together used an Intel 4040 4-bit microprocessor, the second made by the company and released in 1974. The 4040 was used that year in Bally’s Flicker prototype, developed by Jeff Frederiksen at Dave Nutting Associates, but it wasn’t the first microprocessor used in an amusement device (that right goes to the wall game Bally Alley). It was, however, one of the first used in a pinball table. It arrived just in time for Sega, Bally and others to use it to revolutionize their pinball games. Sega bought development tools from Intel, and Yoshii began writing programs for the new chip in Assembly language.

The 1970s were a turning point for the pinball industry, as solid-state technology created new possibilities of play, greater reliability, and set the stage for even more sophisticated, interactive machines that defined the contemporary arcade era. Bally Manufacturing followed suit, releasing versions of its Fireball and Boomerang tables. Williams arrived a bit after Sega with Hot Tip, its first solid-state game to go into full production.

Sega turned heads with Rodeo at its tournament, and the game had a good run at 25 game centers all around Japan during the promotion. It has another distinction in Sega history, though. It was the first project assigned to a recent hire named Hiroshi Yagi, the man who would go on to design the Game Gear portable console. Sega’s new pinball division was his first stop on the corporate ladder, and he learned the ins and outs of its electromechanical games by fixing wiring and other defects before they shipped.

Beyond promoting new pin games like Rodeo, Sega had another motive behind the tournament. The company sought to inject some excitement into pinball. Sega hoped that the tournament could help bring the industry together to work towards bringing coin-op games to a wider audience. The tournament’s resounding success was considered the first step in that direction. It was marked the first time such a major competition had taken place in Japan. To this point, small-scale events had been held for pinball, bingo, video games, and air hockey, but nothing on this scale had ever occurred. 13,000 people were a huge crowd for pinball, surpassing even Sega’s expectations.

Alongside the tournament, Sega unveiled its products to 350 distinguished guests at exhibitions at hotels in Tokyo and Osaka in May 1976. Presentations for pinball games like Rodeo were made, but Sega also promoted its medal games, including the Black Jack and medal-type pin game called “Jackpot Flipper.” These medal-type pinball games weren’t original designs but rather existing pinball tables that Sega modified, such as Stretch Drive, which was a modified version of Sega’s own Winner. The concept was based on standard pinball, and games were usually played with three or five balls per play (the amount could be adjusted via settings, but it was commonly operated with three balls). Medal rewards or losses were determined by how high a score a player could achieve using just a single ball, and players attempted to get the highest score possible on one ball to win a medal. Basically, the game could be played with just one ball, but inserting additional balls triggered an internal lottery. If players won this lottery, the score required to receive a medal payout would drop. Sega produced around eight Jackpot Flipper tables over the course of a year, with a few conversions of Williams tables like Best Hand and Spanish Beauty.

All the new types of games on display were highlighted by newly-appointed Vice President and Chief Operating Officer Duane Blough, one of only two Americans in management at Sega of Japan. Blough came aboard in 1976 to replace Harry Kane and remained in Japan for five years before coming stateside to Sega Enterprises Inc. Blough used the events to highlight Sega’s new and aggressive sales policy that had two priorities. First, Sega would be aggressively developing game machines in new categories, as seen in the products presented during the exhibition. Second, it would like to respond to the needs of customers and operators with more services, like mechanical training.

Sega’s original pinball products continued to improve throughout the decade, evolving from the early designs that emulated its competitor’s tables to more innovative designs. “For the basic parts of pinball, like the placement of bumpers and flippers, we referred to Bally and Williams, so I don’t think there were any major differences from their machines,” Yoshii told the author. Later machines incorporated more advanced features, such as the two small shrines in 1977’s Mikoshi, based on the Japanese portable Shinto palanquin traditionally believed to transport gods between shrines. The game’s playfield included two small shrines with bells that swayed and deflected the ball. “On Mikoshi’s playfield, two portable shrines were placed, and a new mechanism was added that allowed the ball to automatically travel back and forth between the two shrines,” Yoshii said. It was a neat feature, but Sega wouldn’t have much longer to build on its innovation. Things were happening in the coin-op space that would slowly push it out of pinball.

Last Ball to Drain

The end of the 1970s saw Sega in a much different place than it was at the start. As it continued to release pinball tables in its Japanese game rooms, Sega was also dipping its toe into the U.S. arcade scene. In 1976, it acquired a 100 percent stake in the California mall arcade chain, Kingdom of Oz. Though only six locations, the chain was an auspicious start, and it was in 1976 that Sega brought Rodeo to the U.S. market. By 1978, the publisher had locked down around six percent of the electromechanical market, but it now turned its full attention to the video game sector. It would be here that Sega would rise to become one of the most dominant amusement companies of all time, but sadly, pinball would not be along for most of the ride. In fact, Sega exited the pinball industry in 1979 to devote its resources to video games.

Even though Sega had a solid lineup of pinball tables that were cheaper than imported American machines, it was unable to maintain the momentum it had when Winner launched in August 1971. Even its innovative Jackpot Flippers weren’t sustainable, despite the popularity of medal games in Japan. Listings for the machines showed a significant price drop from 1977 to 1978, suggesting a decline in public interest. Some tables dropped to the clearance sale price of half their original listing cost of 360,000 yen, a huge decrease in only a year. The drop could have happened because Jackpot Flippers were quite difficult – a typical coin-op tactic to squeeze as much money from players as possible – but it could be extremely hard to achieve the highest prize payout. The payout mechanic of Jackpot Flippers was like that of pachinko, but those machines were much more forgiving in their win percentages and much cheaper and easier to produce.

Furthermore, Sega’s pinball games were different from their western counterparts in that they were designed to be easily maintained if operators had the knowledge and skills, but those operators required speedy and complete technical support from Sega itself, something the company couldn’t provide. Operators were unable to obtain the parts and support they needed to keep the tables in working order, directly affecting their earning ability. As a result, they gradually replaced them with other machines. According to Bruce Tsuji, Director of the Japan Game Museum, Sega was much better at making pinball games than it was maintaining their functionality, despite Blough’s proclamations in 1976. “I do feel that Sega Japan was good in innovation and technology but was not good in post-production service and support. I believe this was the root cause of the failure of the pinball business in Japan,” Tsuji told Pinball News in a 2013 interview.

Beyond its problems providing operators with technical support, Sega had good business reasons for pulling out of pinball and focusing on video games. In a sense, its pinball games set the stage for that division’s own demise. Yoshii was the person who received and analyzed one of Atari’s Pong units for Sega, and he used the hardware and schematics Sega had acquired to make Pong-Tron. Video games were the future, and though Sega spent a few years trying to balance pinball with video, once Taito’s Space Invaders arrived in 1978, there was simply no turning back. Sega ceased manufacturing pinball entirely in 1979 after releasing almost three-dozen original and licensed tables. By the early 1980s, quarters were flowing through its video game hits like Monaco GP, Pengo, and Zaxxon. Also, the SG-1000 hit stores, launching Sega’s home console business. Between coin-op and consumer products, Sega had established itself as a major player in the video game industry in its native country and North America, and the next decade would be one of major changes and growth. Sadly, pinball would have to wait for another chance to be a part of it.

Sega-16 would like to thank Masaharu Yoshii for his time and Steve Hanawa for his help in making this article possible.

Be sure to read part 2 (Sega Spain) and part 3 (Sega Pinball, U.S.) of our history on Sega’s pinball games!

Sources

- “Aim to be the Best Flipper in Japan; Preliminary Rounds Begin on May 10, Finals on May 2. Sega’s Nationwide Flipper Tournament Details Decided.” Game Machine, April 1, 1976.

- Greatwich, John. “The Forgotten History of Pinball.” Pinball News, January 16, 2013.

- Highsmith, Alex. “Sega Arcade History: The Formative Years.” Shmuplations, n.d.

- Horowitz, Ken. From Pinballs to Pixels: An Arcade History of Williams-Bally-Midway. (Jefferson: McFarland, 2023).

- —. The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games. (Jefferson: McFarland, 2018).

- Johnson, Ethan. “Exploring the First Microprocessor Video Games.” The History of How We Play, September 11, 2018.

- “Machine Games Make Great Progress Astonishing Popularity and Interest in Flipper National Champion Tournament.” Game Machine. May 15, 1976.

- Morihiro Shigihara, Donghoon Kim, and Hiroshi Shimizu. “Masaharu Yoshii, Oral History (1st, 1): Oral History on Game Development at Sega and Game Industry at the Early Stage.” Ritsumeikan Center for Game Studies, February 2020.

- “Nationwide F Tournament: Preparing for the New Flipper Campaign.” Game Machine, March 15, 1976.

- “Profile on David Rosen: Pace-Setter of Japan’s Coinbiz.” Cash Box, June 29, 1968.

- “Seeburg Cancels Sega Agreement: Notes $5.25 Million Financing.” Play Meter, August 1975.

- “Sega to Acquire Williams; Seeburg to Retain Slot Mfg.; South Atl. Offices to Sega.” Cash Box, March 8, 1975.

- “Sega Enterprises Enters Pingame Manufacturing: Intro’s ‘Winner’ to Japan Mkt., Export Downstream.” Cash Box, July 17, 1971, 43.

- “Sega Enterprises Formed in Tokyo.” Cash Box, August 14, 1965.

- Sega Hardware Historia – Grand History of the Magazines Featuring Sega Consoles, Edited by the Teams Behind BEEP! Mega Drive, Sega Saturn Magazine, and Dreamcast Magazine. (Tokyo: SB Creative, 2021).

- Smith, Alex. They Create Worlds: The Story of the People and Companies that Shaped the Video Game Industry, Volume I: 1971-1982, (CRC Press, 2020).

- “Williams to Wholesale Sega Games in U.S.” Cash Box, November 18, 1967.

- Yoshii, Masaharu. Interview by Ken Horowitz. April 22, 2025.

Pingback: Newsbytes: Bowl Expo 2025 Preview, Dave & Buster’s Leaderboard, Headlines & More - Retro Arcade Solutions

Pingback: Newsbytes: Bowl Expo 2025 Preview, Dave & Buster’s Leaderboard, Headlines & More - Retro Refurbs

Pingback: Arcade Heroes Newsbytes: Bowl Expo 2025 Preview, Dave & Buster’s Leaderboard, Headlines & More - OnGames247

Pingback: Arcade Heroes Newsbytes: Bowl Expo 2025 Preview, Dave & Buster’s Leaderboard, Headlines & More - Arcade Heroes