Thus far, we’ve seen Sega get its start in pinball in its native Japan in the 1970s and expand to Europe throughout the 1970s and 1980s. We complete our journey with an examination of Sega’s pinball run in the U.S. It was the shortest of the company’s tenures in the industry, but it was perhaps the most widely documented thanks to the involvement of someone who practically personifies pinball in the U.S.: Gary Stern.

Thus far, we’ve seen Sega get its start in pinball in its native Japan in the 1970s and expand to Europe throughout the 1970s and 1980s. We complete our journey with an examination of Sega’s pinball run in the U.S. It was the shortest of the company’s tenures in the industry, but it was perhaps the most widely documented thanks to the involvement of someone who practically personifies pinball in the U.S.: Gary Stern.

Sega Pinball was an endeavor with roots extending long before its founding. It went on to become Stern Pinball, a company that endures to this day. Despite its short duration, Sega’s pinball experience made an impact on that industry that helped shape the current market in ways still felt and seen today.

Seeds in the Golden Age of Gaming

To get the full context of Sega’s pinball business, we must go back over a decade earlier, to a time when the company was still trying to return to the North American coin-op space. At the dawn of the 1980s, Sega was actively trying to make its mark in American arcades through games imported from Japan, like Zaxxon and Frogger, along with original titles developed and manufactured by its R&D and manufacturing hub, Gremlin Industries. Sega purchased the developer in September 1978, finding great value in its wall and video games, and Gremlin would provide Sega with multiple arcade titles over the next five years, including classics like Carnival (1980) and Space Fury (1981). The one area the firm avoided was pinball, leaving the U.S. market to the big pin houses Bally, Gottlieb, and Williams. Sega/Gremlin instead focused on video games, a field that was soon also invaded by the pinball companies, as well as a myriad of new companies, some of which were started by long-established industry veterans.

Sam Stern was one such veteran. He had been with Williams since 1946, aside from a short stint in 1969 as an executive vice president at Bally, and he retired in 1976. As dynamic and creative as he was, it didn’t take long for him to become bored, and he joined with his son Gary to begin a new pinball adventure. Gary had been around pinball his entire life, starting as a stockboy over the summer at Williams at age 16. He spent many summers there, working in inventory, human resources, accounting, and even in the design department. His father convinced him to go to law school after he completed his degree in accounting from Tulane University, and he graduated in 1971. After a few years working in corporate bankruptcy, Gary decided that his heart was in pinball. He joined his father at Bally as a law clerk specializing in slot-machine law, and in 1973, they both returned to Williams Electronics, where Gary was the president’s assistant and headed a new project to challenge Bally in the slot-machine industry. Williams wasn’t successful in those efforts, and Sam Stern retired once more, so Gary quit Williams in 1976. He and a friend named Steve Kaufman then formed a company called KISS Amusements that distributed slot machines to Canada. Shortly afterward, Gary rejoined his father to acquire the pinball assets of Chicago Dynamic Industries, known as Chicago Coin, after it went bankrupt in 1976. Their new company was called Stern Electronics.

Now, Stern Electronics is not the same company as the Stern Pinball that makes so many awesome pinball tables today; they are two completely different entities. We’ll get to Stern Pinball later in this piece, and while the Stern Electronics we need to discuss first has no direct relation to that company, it set the foundation for what was to come by helping shape the man who would found the largest American pinball company around today. It also shared some Sega DNA in that it was partially financed by Martin Bromley, who received half the company’s voting stock.

Stern Electronics entered pinball at a difficult juncture, one where the industry was moving to solid-state technology and where video games were rapidly gaining popularity. The Sterns were able to navigate these challenges to become the fourth largest pinball manufacturer in the U.S. with hits that included Meteor (1979) and Flight 2000 (1980). They then expanded their business into video games, as just about everyone else did at this time, and released a string of original titles like Berzerk (1980), along with licensed games such as Konami’s Scamble (1981) and Valadon Automation’s Bagman (1982).

The turbulent North American arcade landscape of the early 1980s soon turned these successes into financial hardship. Sam Stern died in November 1984, and his company was unable to survive the crash that hit arcades in the U.S. at the time. It ran out of money and ceased operations in 1985. Gary didn’t remain out of circulation for long, and he soon rebooted with Carrin Electronics to produce circuit boards for telephone systems, a new venture he started with Stern Executive Vice President Tony Trocano. It wasn’t pinball, but that wouldn’t be too far behind.

(Data) East Meets Mid-West

One of the big arcade makers during the mid-1980s was a Japanese firm called Data East. It had been making video games since 1978 and had had endeared itself to arcade goers with Burgertime (1982), Karate Champ (1984), and Kung-Fu Master (1985). Data East was no stranger to expansion, having opened its North American branch June 1979 and its European office in March 1985. It also had a consumer division that produced software for home machines like the Nintendo Famicom and MSX personal computers. One area it hadn’t yet reached into was pinball, and it had been contemplating ways to enter that market for around four years. Data East’s leadership considered the company to be a coin machine company and not just a video game business, so adding pinball to its lineup made sense.

Meanwhile, Gary Stern had spent the time since Stern Electronics’ folding doing several different things to stay in the industry. He worked with a company called Video Vendor that dealt with video cassette rentals and purchases (think Red Box but with VHS tapes) and started a new outfit called Pinstar that sold a multi-ball pinball conversion of Harry Williams’ Flight 2000 called Gametron. It was manufactured by KitKorp and cost half the price of a new pinball table, replacing existing parts like the playfield, backglass, and side graphics. It looked good and was designed by Steve Kirk, who had done several tables for Stern Electronics, including the popular Meteor. The only problem was that not enough people wanted it. Few operators were willing to buy a conversion kit, even if it was cheaper, because they got more value out of their existing pinball machines. “We proved the concept didn’t work because why would you take your money, buy a kit, take your used pinball machine, put this kit in it and add something without a resale value when you could trade in your game and buy a High Speed [Williams hot new table designed by Steve Ritchie]?” Stern admitted in a 2020 interview.

Stern decided to move on, and what he really wanted was to get back into designing and manufacturing pinball games. He worked with Shelley Sax, who had been his assistant at Stern Electronics, to come up with a plan for a new pinball company. They tentatively called it “Newco” (New Company). Stern and Sax then joined forces with Joe Kaminkow, a game designer who had a talent for securing licenses. Kaminkow had grown up around coin-operated machines due to his father’s business venture in the field, and as a young man, he wanted to develop pinball machines despite having no experience in design. He learned the hard way by developing and distributing games as a teenager and eventually became the vice president of a large chain of arcades called That’s Entertainment. Having lost faith in other pinball developers, he believed he could do better and co-founded Logical Highs in 1981. Kaminkow leveraged his contacts to get a deal with Williams where they secured the first option on his designs and would translate hit video games into pinball form, starting with Defender Pinball (1982). The success led to a job at Williams, where he secured the licensing rights from NASA that resulted in Space Shuttle (1984), the game that saved Williams’ pinball business. Now, Kaminkow would combine his design and licensing expertise with Stern’s business acumen to launch a new venture.

Stern, Sax, and Kaminkow, with some funding from a friend named Ed Pellegrini, kicked the idea of starting a new pinball house around a few companies, including Konami, but their emphasis was on Data East. “Bob Lloyd was running it, and he was intrigued with the idea of a product that didn’t come from Japan that he had more control over and that he could sell worldwide instead of just in the U.S.,” Stern explained. He met with Data East representatives in the coffee shop of the O’Hare Hilton Hotel to make his pitch about why it should take on Bally, Williams, and Gottlieb, and they agreed to hear him out. Together with Kaminkow, Stern made their presentation for a Data East pinball division to Lloyd, Vice President Steve Walton, and company founder Tetsu Fukuda, in the basement of Stern’s own townhouse. He emphasized the resurgence in the pinball market at the time and how Data East was involved in every other aspect of amusement. He also stressed the benefits of selling an American-made product (a point that Lloyd supported). The pair made a convincing argument, and Data East Pinball was born.

The fledgling company set up shop in two tiny rooms in the corner of a “slightly condemned” 400,000-square-foot location on Peterson Avenue known as the Rigo Building (now Sagenosh Village), which had previously been used for manufacturing. The place was in such bad shape that its shredded reddish-orange rugs stuck to their feet whenever they left, leaving shaggy footprints behind them. The staff shared a single gas heater and even had to haul their own garbage home because there was no collection service.

Data East Pinball made its debut at the 1987 ACME show in New Orleans with Laser War, designed in almost no time by Kaminkow. They stripped a Williams 1986 game, Road Kings they had bought and rewired it to shoot the ball and pop some field pop targets to make sure it worked. “I started on Thanksgiving Day 1986. It was a Thursday. By Monday I had a finished playfield design, and by the end of the week we had a working whitewood,” recalled Kaminkow. Laser War was supposed to be Laser Tag, based on the popular infrared-emitting light gun toy, but Data East Pinball couldn’t get the license. The game was even presented to distributors at a Laser Tag arena (possibly Laser Zone on Lawrence Avenue). During a Laser Tag game, Kaminkow ran into a low doorway, splitting his bottom lip and knocking himself out cold.

It took a lot of effort to get the four Laser War machines ready for the ACME show. “We started with eight of them,” Kaminkow explained at a 2025 Pinball Expo panel. “I think we eventually got four of them on the floor and kept stealing parts from anything we could to get the games running. Eugene [Jarvis] was kind enough to grab a few parts off the Williams line, as he was on the way down with F-14 [Tomcat] with the chips in his hand.” By about midnight after the first day of the show, there was concern that Laser War’s software wouldn’t function properly. One issue was that none of the game’s three color-coded ejects would release the ball. Kaminkow solved the issue by simply screwing a post in front of the poles to keep the balls from going in. Eventually, Data East Pinball was able to get the ejects to function properly, and the machines operated relatively problem free for the rest of the show.

Laser War was the first pinball table to incorporate stereo 2.1 channel sound (two speakers and a subwoofer) and sold over 2,500 units. Though it seemed at the time that the game could fail commercially and doom Data East Pinball before it even started, the machine was a hit. It started a string of solid original titles that was enough to help the company move from its tiny 1,500-square-foot corner space to the entirety of a 26,000-square foot facility. For the next two years, Data East produced machines designed by Kaminkow and other talents like Ed Cebula and Claude Fernandez. Cebula worked with Kaminkow on 1990’s Phantom of the Opera, the game that made Data East Pinball profitable. “If Phantom of the Opera had not happened, if Ed Cebula had not been there to hold my hand for that game, this company would have never survived. That was really our turning point game,” Kaminkow admitted in 2025.

Early on, Data East looked to bringing its Chicago-made pinball games overseas, including Japan. The marketing and sales staff at the company’s main branch knew little about the business and brought in someone knowledgeable in an effort to catch up. One of those new recruits was Masaya Horiguchi, who had been a pinball fan since elementary school, enjoying the multitude of games available during the industry’s Japanese heyday in the 1970s. His love of the game only increased as he got older, to the point where he and his high school friends would document techniques for flippers and gunching (movements players make while playing to influence the path of the ball). He was saddened to see pinball lose its place in Japanese game rooms as video games took over. “I remember seeing rows of arcade cabinets where pinball machines had been just yesterday. Seeing the indentations where the machines’ legs had sat on the floor or patches of untanned wall made me wistful: “there used to be a pinball game here,” he recalled in a 2017 interview. Like many others, he turned his attention to video wonders like Space Invaders, but pinball wasn’t done with him quite yet.

After graduating and joining the workforce, Horiguchi found that his limited free time wasn’t enough for playing both video games and pinball, so he defaulted to his first love (he was skilled enough at pinball that could make his yen go farther by accumulating multiple free credits). It was a fortuitous decision. As a founding member of the Tokyo Pinball Organization (TPO), he often attended the Amusement Machine Expo, where he played pinball at the Data East booth. “I would always discuss sales promotion strategies with the sales staff there, telling them, “You should highlight this part of the game,” and stuff like that,” he said. “Eventually they said to me, “If someone as knowledgeable as you, Mr. Horiguchi, could join us, it would be a huge help.” He went to work for Data East in April 1988, debugging machines and creating instruction cards and manuals for the modern Japanese pinball customer.

Alongside Horiguchi, Data East sent several of its video game staff to Chicago to support circuit board design and foundational development tasks, including Takashi Ishikawa, a former Sega pinball expert who brought valuable experience in basic manufacturing. Horiguchi was also now tasked with sales and promotions, and some of his ideas were adopted in Chicago. “Data East issued playing manuals starting with their second title, Secret Service, but those were still primarily planned by the advertising department. Starting with the third game, Torpedo Alley, they entrusted me with everything,” he recalled.

Eventually, Data East Pinball shifted its emphasis from original titles to licensed ones. The decision wasn’t exclusive to Data East, as Bally had been licensing properties for its tables for years, and Williams began focusing more on them during the latter half of the 1980s. Bally leaned heavily on licensed titles during the 1970s, thanks to the vision of its Vice President of Sales Tom Neiman, who normalized the practice between 1972 and 1984. Bally stepped back a bit from its dependence on licensing in the 1980s, leaving a void that Data East quickly filled. Licensing had its downside, to be sure, such as the cost of using a property that was in demand. “If you make a stuffed animal that looks like a mouse, you’re not going to sell it unless you pay Walt,” Stern often said. Licensing also presented restrictions on designers who had to remain true to the property they were using. That being said, licensing was very beneficial for pinball companies for multiple reasons. First, they were quick to grab the players’ attention, offering them something with which to identify. A generic game about dinosaurs wasn’t as eye catching as one based on Jurassic Park. Also, the specific parameters of a property provided a starting point for designers because there were already characters, settings, and conflicts fleshed out for them. Additionally, licensed properties gave designers a chance to obtain an outside perspective from the companies who owned them, one beyond that of the people working within the factory environment. Finally, the popularity of many licenses made them much more sellable to consumers. Stern summed it up thusly: “If I call somebody and say, ‘I’ve got Zombies from Hell,’ the customer is going to say, ‘Send me two or three, and I’ll see what they look like and I’ll test them and so forth,’ but If I say, ‘I’ve got The Walking Dead,’ they say, ‘Send me a container.'”

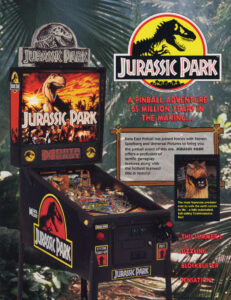

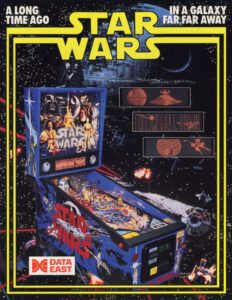

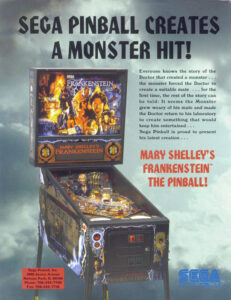

Data East’s first licensed table was Kaminkow’s Playboy (1989) that had art by the legendary Kevin O’Connor. It opened the door for machines based on huge properties like RoboCop (thanks to Data East having the arcade license for its coin-op game) and Back to the Future (1990), which was designed and built in only six weeks. Each licensed table sold more than the one before it, and Data East Pinball found its breakout title in The Simpsons in 1990, of which over 5,500 were sold. Data East’s biggest licensed seller was 1992’s Star Wars, which moved over 10,000 units and was the first table designed by Jon Borg, who had started at Gottlieb as a draftsman/mechanical engineer. Borg’s debut assignment was Hook (1992), and he started working on a playfield based on Jurassic Park that had a mechanical dinosaur that could eat pinballs and even throw them back at the flippers. When Kaminkow offered him the Star Wars license, Borg adapted his concept and switched out the dinosaur for the Death Star (the ball-tossing figure would finally appear in 1995’s Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein under Sega). T-Rex would get another chance to terrorize playfields when Jurassic Park, designed by Kaminkow, Borg, and Cebula, debuted in 1993. In it, the dinosaur would eat the ball. That game was almost Cadillacs and Dinosaurs instead of Spielberg’s blockbuster. Data East Pinball was going to do a licensed table based on the comic book and short-lived cartoon series as a favor to then-Sony Executive Vice-President Bernie Stolar (yes, that Bernie Stolar). After securing the license because a motion picture was supposedly in the works, Stolar then reportedly offered it to Williams for more money. After losing the license, Data East Pinball landed Jurassic Park instead.

For a company that began from zero, Data East Pinball made several major innovations to the pinball industry that forever changed how such games were designed, manufactured, and distributed. It was Data East that introduced pinball standards like the dot-matrix display with Checkpoint in 1991, an addition that paved the way for video modes in pinball games. The Simpsons was supposed to debut the technology, but Data East USA President Joe Keenan was concerned that it wouldn’t be ready by the time the game shipped, and problems arising from a rushed production could potentially put them out of business. The dot-matrix screen was thus held back for Checkpoint the following year. The screen was only half the height of screens used by Data East and other pinball makers later, and the larger screens soon became the standard.

Another major advancement made by Data East Pinball was the solid-state flipper. Most pinball machines, aside from the earliest models, used two winding flipper coils – one power coil and one low power (hold) coil to keep the flipper in position. Even more modern solid-state systems, like Williams’ “Fliptronics,” still used the two-coil system. Data East simplified this process by using a system that used one winding for both the power and hold functions by changing the voltage to the coil. This reduced the complexity in that there were now only two wires to the coil. 1989’s RoboCop replaced the old electromechanical flippers with this new technology, and Data East Pinball was so confident that it would greatly reduce flipper coil burnout that it offered a one-year guarantee for a free replacement if they failed.

There’s a story behind those flippers whose truth won’t likely ever be told. Data East Pinball’s DE-0264-1 display controller board bears more than a simple resemblance to the one used in Williams’ System 11, and Data East Pinball was accused of plagiarism. Reportedly, Williams sought to patent as much of its technology as possible (that even included the term “multi-ball,” which is why later revisions of Data East Pinball’s Lethal Weapon 3 games named the feature “tri-ball”). Williams’ board simply switched between different windings of a coil to prevent overheating without adjusting the voltage. Data East Pinball’s flipper board was reportedly different because it prevented coil overheating by varying voltage, eliminating the need for multiple windings. So, while Data East could be accused of taking inspiration in other areas, flipper design wasn’t one of them. When Data East created its first board using the solid-state flippers, the designer was supposedly so mad at the accusation that he called it the TY-FFASI, which supposedly means “Take Your Fucking Flipper And Shove It.” What truth there is to these allegations will likely never be known – no one’s ever going to admit anything – but it does make for a neat story! Pinball is full of them.

Williams also acted when the aforementioned Jurassic Park arrived in 1993. Staff were not pleased with the T-Rex, despite him no longer having the ball-tossing mechanic. They took issue with his ability to follow the ball around the table and growl at it, considering the actions to be a direct copy of a 1992 patent Williams had for Pat Lawler’s Funhouse table, which featured the talking head of a doll named Rudy that, along with spitting the ball out after players shot it into his mouth, would also follow it with his eyes. Williams staff went to where Jurassic Park was being tested, the Rock and Roll McDonald’s, a famous burger location in the touristy area of Chicago, and filmed video of the game in action. Ultimately, Data East altered its software to remove the feature, preventing any legal action by Williams.

The battles with Williams were a constant issue. Most distributors were barred from carrying pinball machines from other companies if they had a deal with Williams, a power move that company could pull off because of its size and sales volume. Similarly, a show of gratitude by Kaminkow resulted in the loss of several suppliers. “Joe, in his wisdom published in Replay a thank you to all of our suppliers which Williams read and no longer allowed them to supply us. So, we lost all we lost a lot of our suppliers because we thanked them.” Kaminkow got a bit of payback by taking advantage of an Illinois law that forbade the disassembly or dumping of a competitor’s software code. In several Data East tables, he included in the first line of his ASCII code a message to Williams Executive Vice President and General Manager Ken Fedesna and Director of Pinball Engineering Larry DeMar that he knew they were snooping around, along with an invitation to call him and join him for lunch one day, “which pissed them the fuck off,” Kaminkow gleefully recalled.

Data East Pinball’s most important innovation was bringing back licensing as a major component to pinball design. As mentioned earlier, there had always been licensed tables to sell; Atari’s Superman and Bally’s KISS (both from 1979) are great examples. Data East saw big success with its licensed machines, with Lethal Weapon 3 and Star Wars each topping the 10,000-sold mark. It started its licensing efforts only four months before Williams, where that factory’s Director of Marketing Roger Sharpe saw the same potential revenue stream as Kaminkow, and the two competitors spent the next several years exchanging a barrage of licensed releases. Even as the old guard of companies has faded and has been replaced by newer manufacturers, licensing remains a pinball standard today.

As Data East Pinball reached the midpoint of the 1990s, the pinball market was undergoing a radical change. Sales and revenue were declining thanks to competition from other forms of entertainment, like increasingly powerful home game consoles. Many within the industry believed that the drop in the coin-operated amusement business was due to several factors, such as reduced buys by small operators, high debt levels by some distributors and operators, and the popularity of big family entertainment centers (FEC). These large operators were indeed performing well, increasing their services with facilities like leagues, music, and food. Still, pinball’s downturn resulted in casualties. Alvin G. & Co., a new startup from the son of Gottlieb’s original founder, David Gottlieb, closed its doors in March 1994 after only three years in operation.

The last pinball machine produced by Data East was 1994’s Maverick, based on the Mel Gibson western film. It was also the final table designed by Tim Seckel, who entered the pinball business when he was hired by Data East in 1990. Seckel’s style favored an emphasis on orbits (a curved path for the ball that hugs the outer edge of the playfield) and shots that didn’t require ramps. Seckel departed Data East as pinball began to decline, as sales factored greatly in designers’ salaries. Although Maverick entered production under Data East, it would be released under a different brand, one that was about to make its debut with all the flair and pomp of a jackpot multi-ball.

SEGA!

It was midway through 1994, and Data East President Tetsuo Fukuda had a problem: his company was having a rough time financially. It was deeply in debt and hadn’t been able to find a way out. Even though Data East Pinball provided 74 percent of his U.S. subsidiary’s total revenue, and it controlled around 25 percent of the North American pinball market (second only to Williams), it simply wasn’t enough. The division was profitable, but Fukuda could see that overall, Data East was in serious danger. He tried consolidating the U.S. arms of his video game and pinball manufacturing in Chicago in 1994 (Data East’s video games were previously made in California) but couldn’t bridge the gap. That same year, he opted to get out of pinball entirely while there was still time and focus instead on video and redemption games. Some of the first projects in the pipeline were the digitized fighter Tattoo Assassins and a basketball title called Street Slam.

Enter Sega, a company that was just about everywhere in the 1990s. It was battling Nintendo in the console space, innovating in arcades, and even getting into amusement centers and larger themed rides like its AS-1 simulator. The gaming giant was at its highest point and even saw Disney as a rival worth challenging. Sega also had a lot to do with Data East’s future as a game company. It owned around 17 percent of Data East stock, and the two factories had collaborated on a solid-state electronic pinball system that Data East used in several of its machines. It wasn’t in Sega’s interest to see the company fail, so rather than simply pour cash into it, buying Data East Pinball seemed like the most logical step. Sega had been pushing the boundaries of arcade technology with Virtua Fighter and other 3D marvels, and pinball was one of the few coin-op areas in which it still lacked a presence. Perhaps Japan was still feeling the sting of pinball’s fall in that country, but North America was a different story. It’s not clear why Sega waited so long to enter the market and why it chose to do so during a slump, but it launched its first ball with the August 1994 announcement by Fukuda and Sega CEO Hayao Nakayama that Sega had purchased Data East Pinball for $36 million. The acquisition doubled Sega’s American coin-op presence, giving the legendary publisher another weapon to add to its arsenal that included video game and redemption lines.

Although Maverick was the last Data East pinball table to come off the line, it only did so after Sega’s takeover. Since no one knew exactly when the name of the company would change, by the time the game shipped it was too late to add Sega’s logo to the machine (it did appear on the dot-matrix screen). Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein would be the first table to properly feature Sega’s logo on the cabinet. Interestingly, the aforementioned Tattoo Assassins was already in production when Sega took over, and the Data East Pinball personnel that were contracted to make it, including Kaminkow, remained on Data East’s payroll until it was finished.

Initially, there was some apprehension about Sega’s arrival. Would business continue as always, or would the new owner rewrite the company culture and eliminate pinball? Horiguchi recalled that Data East’s Japanese staff were quickly reassured that their positions were safe. “A meeting was held at Sega headquarters regarding our future pinball operations, since the acquisition involved not only new pinball machines but also aftercare for existing tables. Mr. Ishikawa and I attended. Contrary to expectations, it concluded with them saying, “Data East, please continue working as you have been.” Gary Stern viewed the buyout as viewed as a good thing. Not only did Sega leave the corporate structure intact and guarantee employment for its factory staff, but it also opened the door to larger projects. Stern summed up the change as “more reputation, more money to play with, more credibility with distributors.” Sega was much larger in size and scope than Data East, and it had much deeper pockets to provide the resources needed to make the complex tables that defined modern pinball. Licenses were extremely expensive, and their costs were one of the problems that had plagued Data East. In contrast, Sega could finance big name properties, and thanks to relationships established during Data East’s tenure with heavy hitters like Steven Spielberg and Bob Gale (writer of the Back to the Future trilogy), Sega Pinball had an inside track to get first crack at major licenses like The Lost World and James Bond.

The added resources of a much larger company also allowed Sega Pinball to also resume producing redemption machines, something it had only started doing during the latter part of its time under Data East as pinball sales slowed down. “We recognize that with its cyclical nature the pinball business is at a lower level,” Stern admitted at the time. “We have adapted our business with the intent to make fewer pinball machines and at the same time broaden our product base to include redemption games and manufacturing for Sega USA.” The domestic redemption market was quite crowded at the time, as Sega Pinball wasn’t the only factory looking to supplement its sagging pin game sales. Williams had always made bowling and redemption games, and there were other companies that were already seasoned in the genre. Despite the intense competition, Sega made a solid effort in the redemption space, releasing several machines, including one based on its Sega Sports line (designed by Jon Borg), where players competed in basketball, hockey, and football by rolling tokens up a ramp to make baskets or score goals or touchdowns. One of its oddest redemption games was Cut the Cheese, where players rolled coins down a playfield to “flush” them into holes to spell J-A-C-K-P-O-T and win tickets. There was a motorized toilet at the bottom of the playfield that advanced the jackpot and awarded more tickets. They could even use a shaker control to dislodge stuck coins. According to Kaminkow, Cut the Cheese drew the ire of Sega, which was debuting its polygonal marvel Virtua Fighter at the same time. “They’re like, ‘Look, this game has, you know, 15 million moving polygons a second, and it is unbecoming for Sega to be making a game with a toilet on it and a quarter,'” Kaminkow recalled. When Sega revealed that Virtua Fighter was making around $400 a week during testing, Kaminkow shot back that Cut the Cheese made around $1,500 a week from play. The issue ended there.

With all the money and resources at its disposal, one common question that often gets asked is why Sega Pinball never produced a table based on Sonic the Hedgehog. He was the company mascot, known worldwide, and a Sonic-themed Genesis pinball title called Sonic Spinball had been released in 1993. All the ingredients there, yet somehow the game never materialized. According to Stern, Sega was extremely protective of its iconic mascot and wouldn’t even greenlight a redemption title using him. “We had to fight just to put the Sonic logo on our fax forms,” added Shelly Sax. It’s puzzling why Sega chose to be so protective of its mascot when it came to pinball, particularly when the game would have been designed and manufactured in-house. The company has never been very strict about licensing Sonic, and the character has appeared on lunchboxes, pajamas, and just about everything conceivable. A Sonic redemption title was even released by Pearl Development Corp. and distributed by Sting International in 1993, so there was precedent for at least one product in that genre. Still, it never happened. Could it have been because Pearl and/or Sting still had the license? Perhaps it had to do with the newness of modern American pinball to Sega’s Japanese management; Sega of Japan had not been involved in pinball since 1978. Maybe it was because of the lack of familiarity of its U.S. coin-op leadership with the pinball market (Data East’s Vice President of Sales, Tom Petit had been at Atari during its coin-op heyday, but it’s unknown if he had any involvement in its short-lived pinball venture. He departed Data East in 1985 to start Sega Enterprises USA with Gene Lipkin, but that division was not involved with pinball). Any of those reasons are plausible but seem unlikely.

Another possibility could be that Sonic arcade titles just weren’t as successful as their console releases. A 1992 puzzle title called Sonic Brothers never made it past the testing phase due to poor performance, and 1993’s SegaSonic the Hedgehog shipped at a time when the fabled Sonic Team, the core group responsible for making the console Sonic games, was in flux. The AM3 development team behind the arcade title was inexperienced, and its choice of a trackball as a controller soured the game with Sega’s American consumer branch on further titles. “We have developed two Sonic arcade games that have never been released because they were not the specialness that Sonic was. We are continuing to look and see if we can do something with Sonic in the arcade. There is a Sonic arcade project, but nothing scheduled for release,” explained Sega of America marketing head Al Nilsen in 1993 when asked about a potential domestic release for SegaSonic the Hedgehog. Another Sonic arcade release, Sonic Fighters (1996) did ship but received mixed reviews. In the end, it’s possible that Sega’s inability to recreate the Blue Blur’s console magic in arcades made them unwilling to give him a pinball table.

Even today, Sega has never licensed Sonic for an official pinball table. The closest we’ve seen thus far is a fan-made Sonic the Hedgehog Spinball machine by restoration specialist and competitive pinball player Ryan McQuaid in 2021. I played the latest version at the 2024 Pinball Expo in Chicago and it was incredibly well done, full of modes from each classic game and tons of objectives. There was always a line to play it, and people were impressed to learn that it wasn’t an official table. McQuaid’s work was so professional that American Pinball hired him as a designer in 2022.

Sega Tries for the Extra Ball

Pinball in the U.S. continued its slow decline year after year, and by 1996, many were genuinely concerned that it would never rebound. The demise that same year of Premier Technology, another attempted rebirth of the Gottlieb brand, seemed to confirm those fears. Gary Stern, however, was confident that the slump wasn’t the end. “Pinball will return,” he predicted. “It’s always been a cyclical market. We are all working on significant improvements and changes to the game to hasten its return to the upside of the coin-op cycle. We’ve listened to our customers and our competitors’ customers and heard that not only do we need to design rule sets for great players, but we have to have games that for the average player are fun.” Stern’s comments about rule sets had merit. Williams designers Pat Lawler and Larry DeMar had seen the consequences of complicated objectives with their 1993 table Twilight Zone, based on the popular 1960s television series. During its first night of testing, a young man came in and tried the machine. He activated one of its objectives, called the Power Ball, that switched the regular ball to a lighter, ceramic one that moved faster. “He had no idea what to do with it, and he had no idea how to get rid of it. He threw his hands up into the air and screamed, ‘I HATE THIS GAME!’ and walked away,” Lawlor recalled. If Sega was to retain its audience and broaden it, it would have to make its games simpler to play.

In such an uncertain climate, Sega took steps to secure its position. In July 1996 it made a joint announcement with Capcom that the two companies would merge their pinball divisions. “The intention of the merger is to cope with the current market situations, as well as to give the combined company a much stronger market position. Further, by combining facilities and staff, economies of scale will foster a much more efficient and economical operation,” read the statement. Sega GameWorks President Al Stone said that the announcement was just that – a revealing of intentions by two coin-op powerhouses – and that no deal had been finalized. Perhaps attempting to mirror the success Data East had with its American pinball subsidiary, Capcom had jumpstarted its pinball design team in 1993 by poaching designers from Williams when it joined Romstar to form a company called Game Star. Mark Ritchie (Fish Tales, Indiana Jones Pinball Adventure), Bill Pfutzenreuter (Joust, Bubbles), and Python Anghelo (Pin-Bot, Taxi) were some of the bigger names that jumped over to the Street Fighter maker.

A likely reason for Capcom’s willingness to merge with Sega was 47 percent loss it posted in the 1994-1995 fiscal year, a drop that forced it to sharply reforecast its income for 1996 and resulted in the departure of its president, Michael Stroll (formally the head of Williams). Headhunting several of Williams’ designers had resulted in a bevy of lawsuits from that company against everyone involved, and Capcom was one of the prime targets. To avoid even more possible litigation over even the simplest design, Capcom was forced to reinvent everything it used, resulting in skyrocketing costs. Its pinball sector was unable to get a foothold despite a new policy that required distributors looking to stock Capcom video games to also take its pinball wares. As mentioned earlier, many of those distributors already had contracts that made Williams machines the only ones they could carry. Ten distributors dropped Capcom’s coin-op products in the U.S., and the company cut its American staff by 100 people by November 1996. The policy was rescinded a year later.

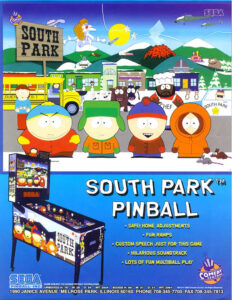

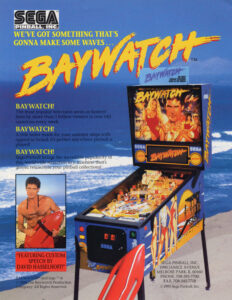

The merger with Sega never materialized, and Capcom Pinball folded soon afterward. Sega continued, producing a line of licensed tables based on some of the most popular properties of the 1990s. Baywatch (1995), Space Jam (1996), The X Files (1997), Godzilla (1998), and South Park (1999) were some of the major licenses Sega secured during its run. Some standout titles of the era were Apollo 13 (1995), which required special non-magnetizable balls to run because of its insane 13-ball multi-ball, and Viper Night Drivin’ (1998), which had balls that glowed under the table’s black lights and music from Guns ‘n Roses guitarist Slash.

Sega also revived its relationship with Incredible Technologies, a studio known for its Golden Tee arcade golf series. Many of the earlier pinball games during the Data East period were programmed by Incredible Technologies, and Sega Pinball renewed the partnership in 1998 to create tournament versions of classic pinball machines. The announcement pleased operators, many of whom felt that modern tables were too complicated to run and maintain. They welcomed a simpler system that would attract multiple players. The first proposed release was Golden Cue: Tournament Edition, featuring Baywatch’s Kelly Packard, despite her having no connection to pinball or billiards. The game was shown at the 1999 Amusement Trades Exhibition International (ATEI) show, but it was never released by Sega. No other titles ever materialized, but Stern Pinball would continue the partnership with Incredible Technologies after Sega left pinball, reworking Golden Cue into Sharkey’s Shootout in 2000.

Sega Pinball had a good chunk of the U.S. market, but it also shipped games worldwide. Around 72 percent of its games were exported to Europe alone, specifically Western Europe, and the thanks to its coin-op sales, the company maintained relationships with distributors in each country. Unfortunately, the pinball slump was also affecting Europe, where many countries had laws that allowed the operation of soft gambling games, like slot machines.

Despite all its efforts, Sega found it difficult to weather the downcycle pinball was experiencing, though it took steps to avoid the pitfalls that had claimed Premier and Capcom. The industry, trying to emulate the success of Williams’ Addams Family, which became the best-selling flipper pinball game of all time, and innovation had become stifled. “Addams Family, I think, won ‘Best Pinball of the Year’ for four years in a row or five years in a row,” said Roger Sharpe, “I mean, it’s an incredible tribute, but what an indictment. That’s like saying that at the upcoming Academy Awards, Titanic is going to win ‘Best Picture of the Year’ again.” Additionally, the aforementioned problem with many games adopting more complex rule sets made them inaccessible to novice players. Sega Pinball attempted to avoid this dilemma by introducing a feature in 1995 called “Guaranteed Time Play” that could be chosen at the start of a game to assure players of at least two minutes of play regardless of how quickly they lost balls. After two minutes, the game returned to standard last-ball play, continuing until the current ball and any won extras were lost. Operators were able to determine the duration of guaranteed playing time. Along with Guaranteed Play, Sega also introduced a four-color process on its playfield that significantly increased the number of colors that could be used, and an icon-based system called “Portals” that made accessing audits, diagnostics, and other operator features more accessible.

Sega Moves On

Pinball was never a major component of Sega’s business in the way video coin-op and consumer products were (as seen by the lack of any pinball games based on Sega properties), so it was not given special treatment when the company began to divest itself of its non-essential components in 1996. Things had changed for Sega during the latter half of the 1990s, and it had transformed from an upstart console maker into one of the biggest names in video games. It was now finding it hard to manage that worldwide success, and cracks were beginning to appear. An appreciation in the value of the yen caused export revenue to drop significantly, and the home video game console market was saturated. Basically, anyone who wanted a Genesis or Nintendo’s SNES console already had one. Add to these issues the fact that Sega had expanded too much and too quickly, along with a major transition of the video game market to newer 3D consoles, and you have a cocktail too potent for Sega to handle. Revenue began to decline in 1993, and the company began to sink under the red ink of unsold 16-bit inventory, strong competition from Nintendo, and later, the incredible success of its rival, Sony. Sega’s Saturn was struggling against the PlayStation, and while things were better in coin-op, the company was not in good shape. Sega needed to trim the fat, and pinball had become an anchor around its neck.

Stern understood Sega’s decision, as unfortunate as it was. “You’re looking at a three- or four-billion-dollar company, in sales,” he conceded. “What does pinball do for them? Not much. For us, it’s a very good, meaningful business. They have been supportive; they’re friends, but we’re just not their core business.” Horiguchi concurred with Stern’s assessment, attributing Sega’s exit to bad timing. Data East had the benefit of entering pinball during a high point, whereas Sega arrived during a downturn. “As a result, it probably felt like they’d been saddled with a liability. Sega had once made pinball machines themselves, but roughly 20 years had passed since then. The game industry had changed dramatically, so it’s hardly surprising they couldn’t get enthusiastic about pinball,” Horiguchi opined. Sega could have simply closed the factory, but Stern’s team was able to convince management that it would be easier and more profitable to simply sell it off. And there was a clear buyer in the wings. Gary Stern himself purchased Sega Pinball on October 1, 1999, and renamed the company Stern Pinball. Data East continued to import Sega Pinball machines to Japan for a short while after the sale, and Horiguchi remained in Chicago after Stern took over, continuing to debug games. Things slowly trickled to a stop, and his last new title was 1996’s Independence Day. Horiguchi’s remaining time at Data East was spent on product aftercare, and when the company offered early retirement, he took it.

Overall, Sega Pinball released 20 tables, as well as several redemption games. The firm was not as prolific as Williams, but it also wasn’t as large. The last pinball game to bear the Sega name was Harley-Davidson, and as its production run continued, it was also the first title produced under Stern Pinball. It had authentic motorcycle sounds taken from actual Harley-Davidson bikes and even a speedometer ramp that displayed the ball’s speed. The game has a unique place in pinball history, having a total of three different production runs over six years and spanning two companies.

Over the years, Sega’s pinball titles have garnered a following among collectors, with titles like South Park (Kaminkow’s last design with the company and his favorite) continuing to rise in value. It’s not entirely fair to say that Sega’s departure left Williams as the last company standing (it would close only three weeks later). All that essentially changed was the name to Stern Pinball. Sega’s factory wasn’t shuttered, and no one was laid off. The same team that ran Sega Pinball was still in place, and Stern, having steered the company under both its Data East and Sega periods, had a clear idea of what needed to be done to keep the firm alive.

Even with all his knowledge and experience, Stern was taking a huge risk, buying out Sega mere weeks before Williams, the largest pinball company in the U.S., was forced to close its doors. By taking the company private, he was banking his own wealth and reputation on the viability of an entire industry, and the odds didn’t seem to favor him. Even so, Stern remained confident. He would produce pinball and redemption games, as well as video games under contract to Sega (the latter never actually materialized), and he would design games meant to attract the average player. If the games were simple and fun, people would play, and he had faith that people still valued a good pinball game. “Pinball won’t die, and for now we just have to tough it out,” he said. “The culture of pinball is just too strong to just fade.” Over a quarter of a century later, his words have been borne out, as pinball has resurged worldwide. There are as many domestic manufacturers in 2025 as there were at pinball’s height in the 1970s, and Stern currently controls around 80 percent of the domestic market. The industry now focuses largely on private collectors and enthusiasts instead of just arcades and game rooms (Stern makes three versions of its tables: pro, premium, and limited edition), but pinball is healthy and vibrant. Sega is no longer a part of the business, but it has also steered itself through the rocky coin-op waters and continues to be a major player in that field.

Maybe someday we’ll get that Sonic pinball table…

Be sure to read part 1 (Sega of Japan) and part 2 (Sega Spain) of our history on Sega’s pinball games!

Updated: October 18, 2025.

Sources:

- “AMOA: Attendance Low, Quality High.” Play Meter, October 1998.

- Ayub, Martin and Jonathan Joosten. “Gary Stern 75th Birthday Interview – Part 1.” Pinball News & Pinball Magazine PINcast. June 12, 2020. Podcast, MP3 audio, 1:18.

- —. “Gary Stern 75th Birthday Interview – Part 2.” Pinball News & Pinball Magazine PINcast. June 12, 2020. Podcast, MP3 audio, 1:29:04.

- “Capcom Coin-Op’s U.S. Video Game Dealers Return to the Fold.” RePlay, April 1996.

- “Capcom to Cut 100 in Japan; Jackson, Scheer, & 10 Distribs Part with Capcom USA.” RePlay December 1995.

- “Cover Story: Sega Pinball.” RePlay, November 1996.

- “Cover Story: Sega Pinball: Nearly 10 Years Old with Founders at the Helm.” Play Meter, November 1995.

- “Data East Celebrated Its 10th Anniversary.” Game Machine, July 1, 1986.

- “Data East Jurassic Park Pinball on Test Location 1993.” Posted on March 8, 2020, by Duncan Brown, YouTube, 20:25.

- “The Early Years at Data East & Sega Pinball – Pinball Expo 2025.” Posted October 17, 2025, by Pinball News. YouTube, 1:31:57.

- “Gremlin Takeover Boosts Sega’s U.S. Market Profile.” Cash Box, October 28, 1978, 72–74.

- Horowitz, Ken. From Pinballs to Pixels: An Arcade History of Williams-Bally-Midway. (Jefferson: McFarland, 2023).

- —. The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games. (Jefferson: McFarland, 2018).

- “How Solid State Flippers Work.” Home Pinball Repair, 2021.

- “Japanese Pinball – Developer Interview Collection.” Shmuplations. August 31, 2025.

- Jensen, Russ. “Gary Stern Talk – Expo ’99.” PinGame Journal, January 2000.

- Kaminkow, Joe. Interview by Jason Roop and Scott Larson. LoserKid Pinball Podcast. September 3, 2021. Podcast, MP3 audio, 1:14:03.

- “Kitkorp to Market First Pinstar Pinball Kit.” RePlay, December 1985.

- “Sega & Capcom Plan Pinbiz Merge.” RePlay, September 1996.

- “Sega Pinball Beings Out New Innovations.” Play Meter, October 1995.

- “Sega USA Buys Data East Pinball.” RePlay, October 1994.

- Shalhoub, Michael. The Pinball Compendium: 1982 to Present (Atglen: Schiffer, 2012).

- Smith, Alex. They Create Worlds: The Story of the People and Companies that Shaped the Video Game Industry, Volume I: 1971-1982, (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2020).

- “Spotlight Special: Data East Pin Encore Says They’ve Arrived!” RePlay, March 1988.

- Stern Gary. Interview by Russ Jensen. PinGame Journal, January 2000.

- “Stern Liquidates, but Gary Opens Carry Electronics.” RePlay, March 1985.

- “Sterns Buy Chicago Coin Assets; Production Resumes in January.” RePlay, January 1977.

Recent Comments