One of the things many Genesis gamers love to note about games made by Virgin and Shiny is just how fluid their animation is. Classics like Disney’s Aladdin, Cool Spot, and Earthworm Jim stand the test of time when it comes to visual quality, and this is in no small part due to the hard work of the animators who emptied their bag of tricks to make the Genesis do what needed to be done. Games like these are why many people still prefer 2D over 3D.

One of the people heavily involved with the titles mentioned above is Mike Dietz. As a supervising animator for Virgin Games and the animation director for Shiny Entertainment, Dietz had a hand in making some of the most fluidly animated games to come to Sega’s 16-bit console, including all three versions of fan favorite Earthworm Jim. Eventually moving on to co-found the Neverhood, Dietz has since worked as an animation director with The Collective and Heavy Iron Studios, where he was part of the team that created Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (Xbox, GameCube, PS2) and The Incredibles. Additionally, he runs his own animation studio called Slappy Pictures LLC, which has done work for Nickelodeon, Disney Interactive, and LucasArts. He has also recently started a new animation studio called Pencil Test Studios.

One of the people heavily involved with the titles mentioned above is Mike Dietz. As a supervising animator for Virgin Games and the animation director for Shiny Entertainment, Dietz had a hand in making some of the most fluidly animated games to come to Sega’s 16-bit console, including all three versions of fan favorite Earthworm Jim. Eventually moving on to co-found the Neverhood, Dietz has since worked as an animation director with The Collective and Heavy Iron Studios, where he was part of the team that created Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (Xbox, GameCube, PS2) and The Incredibles. Additionally, he runs his own animation studio called Slappy Pictures LLC, which has done work for Nickelodeon, Disney Interactive, and LucasArts. He has also recently started a new animation studio called Pencil Test Studios.

Recently, Mr. Dietz gave Sega-16 the rundown on what it was like to work on the Genesis.

Sega-16: How did you end up working on video games?

Mike Dietz: Early in my career I was working as an illustrator and a storyboard artist, mostly for ad agencies. I was a freelancer, so I was always on the lookout for my next job. A friend of a friend said he knew a guy named Brian who made video games, and that I should call him and see if they needed any artwork for the game boxes. I had no idea it was Brian Fargo, the president of Interplay, but I called him up and stopped by with my portfolio. He was nice enough to look at my artwork, but explained that they didn’t design the boxes there, that they had a marketing agency who handled that. However, he said they needed some help with a game they were working on, and asked if I’d be willing to take a test to show them what I could do on the computer. I had never done any computer art before, but I said sure, thinking I could go home, borrow a computer and figure it out before I had to come back and do the test. Instead, Brian walked me into the next room, sat me down in front of a Mac with an old paint program, told me to draw whatever I wanted and that he’d be back in an hour. They had Dungeons & Dragons posters up on all the walls, so I struggled with the mouse and drew what I’m sure was a pretty crappy dragon. I figured he’d come back, look at my stinky drawing and send me on my way, but amazingly they offered me a job.

I freelanced for them on an old Bard’s Tale game and some version of Battle Chess, but I ended up quitting after only a few months. Once the novelty of working on a computer game wore off, I realized creating the low-rez pixel art of that era was pretty boring work. So I went back to storyboards and magazine illustration for a while.

A couple years later I answered an ad for a storyboard artist position at Virgin Games. When I showed up for my first day of work there wasn’t any storyboard work to be done, but they asked if I could animate. I had never animated before, but I was afraid they were going to fire me so I said yes. Steve Crow was working there at the time and gave me tips on how to use the animation software, so I was able to fake it well enough until I figured out what I was doing. I worked for a while on an old version of Monopoly for the PC, but they ended up moving me off of that to be the animation lead on a game called Global Gladiators for the Genesis. Even though the 16-bit graphics look old and chunky now, at the time they were cutting edge and way more satisfying to create than the artwork I had done for Interplay a few years earlier.

Sega-16: The Virgin games you worked on, such as Aladdin and Cool Spot, have such rich and fluid animation. How complex was the process to achieve this on the Genesis? Was the hardware ever a problem?

Mike Dietz: The hardware did have some limitations, but so do today’s systems; you just need to learn how to work within those limitations. The animation we did in those games worked as well as it did for three reasons:

First of all, we had a programmer, Dave Perry, who loved animation and made animation a huge priority in his games. In those days, the programmer was very often the project lead, with final say on allocation of assets and deciding what ultimately went in the game. Dave spent more time and allocated more code, cart/disc space, and effort to animation than any programmer I’ve ever worked with. On top of that, Dave had a great sense of animation timing, was able to see the difference a single frame of animation could make, and therefore was willing to sit with me an tweak animations frame by frame until we got it right. He doesn’t draw particularly well, but I think Dave could have been a decent CG animator if he ever gave it a try.

Second, Dave and I, and later Andy Astor, developed a system for compressing the animation data that allowed us to fit many more frames of animation on the cartridges than most games, and also allowed us to easily stretch the characters into much larger shapes on screen than was normally allowed by conventional game engines at the time. Initially this system required an excruciatingly time consuming process of manually indexing multiple sprites per character per frame using graph paper. I handled this at first and had an amazingly complex matrix of graph paper drawings of sprites pasted all over the walls of my office. After finishing the first couple of games using this manual method we brought in Andy Astor, the biggest brained genius I ever met, and he wrote software to automate the process.

Second, Dave and I, and later Andy Astor, developed a system for compressing the animation data that allowed us to fit many more frames of animation on the cartridges than most games, and also allowed us to easily stretch the characters into much larger shapes on screen than was normally allowed by conventional game engines at the time. Initially this system required an excruciatingly time consuming process of manually indexing multiple sprites per character per frame using graph paper. I handled this at first and had an amazingly complex matrix of graph paper drawings of sprites pasted all over the walls of my office. After finishing the first couple of games using this manual method we brought in Andy Astor, the biggest brained genius I ever met, and he wrote software to automate the process.

Third, we were lucky enough to assemble a team of animators with the talent to take full advantage of our animator-friendly programmer and compression system. Without guys like Shawn McLean, Ed Schofield, Doug TenNapel, Jeff Etter, Eric Ciccone and Clark Sorenson, those first two items on the list would have gone to waste.

There were other development teams out there with talented animators and programmers, but I think we were the first group fortunate enough to have all three of these things going for us at the same time.

Sega-16: Were there any differences in working environment between Virgin Games and Shiny, such as the amount of creative freedom you had or your involvement in the planning of the games?

Mike Dietz: They were very similar. At Virgin we worked as an almost autonomous group, with almost complete creative freedom as long as the games came in on time and were successful. Management treated us well and for the most part left us alone.When we started Shiny, it was the same core group, except we were now working for ourselves. The biggest difference was at Virgin we worked mostly on licensed games, so we were working with someone else’s characters, while at Shiny we did Earthworm Jim and had complete control of the characters and the content.

Sega-16: How did you end up working on Earthworm Jim?

Mike Dietz: When we started Shiny, we had a multiple game deal with Playmates Toys as our publisher, and they offered us several properties we could have chosen for our first game. We came dangerously close to doing the Beavis and Butthead game; thank the lord that never happened. They were also open to hearing pitches for original properties. Ed Schofield, Nick Bruty and I came up with a game based on a character called S.N.O.T. (I can’t remember what the letters stood for), who was a gelatinous blob of goo who could morph into a variety of forms — essentially a comical shape shifter. Ed and I designed the character and did a bunch of pencil test animation to get a feel for him, and it looked like that was the direction we were headed in.

At the same time Doug T contacted Ed, and I and wanted to come work for Shiny as an animator. I loved his work, but some of the other guys weren’t convinced (imagine that!), so I asked Doug to do a test to win them over. The assignment I gave him was to design some sort of alien creature and animate a walk cycle. After a couple days Doug came back with a character he had designed called Earthworm Jim doing a funny, well animated walk cycle. I showed it to the guys and everyone loved it, so he was in. Nick Bruty immediately saw the potential of the character and suggested we do a game with Earthworm Jim. So S.N.O.T. got shelved, although Doug eventually repackaged him as a pet-like creature for Jim.

Sega-16: What was it like working with Doug TenNapel and David Perry?

Mike Dietz: They were both great to work with. Doug is the most creative person I’ve ever seen and a pretty good salesman to boot, while Dave is one of the best salesmen I’ve ever met and pretty darn creative too. When the two of them were working together pitching Earthworm Jim it was a beautiful thing to watch. They both also have that rare leadership ability to rally the troops and squeeze the best possible work out of people, although their management styles are very different. Also, they’re both 6′ 8″.

Sega-16: Were you given freedom to run with the character and his abilities, or were they specified to you?

Mike Dietz: We were literally making Earthworm Jim up as we went along, so we had complete freedom. If it was funny, or cool, or worked well for gameplay, it went in the game. Most of the creative decisions concerning the character had their genesis with Doug and the animation group, even if it was a simple sketch of Jim whipping his head or something like that. It took the entire group’s effort to get anything working in the game, and so everyone had to be on the same page.

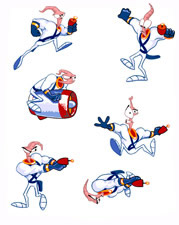

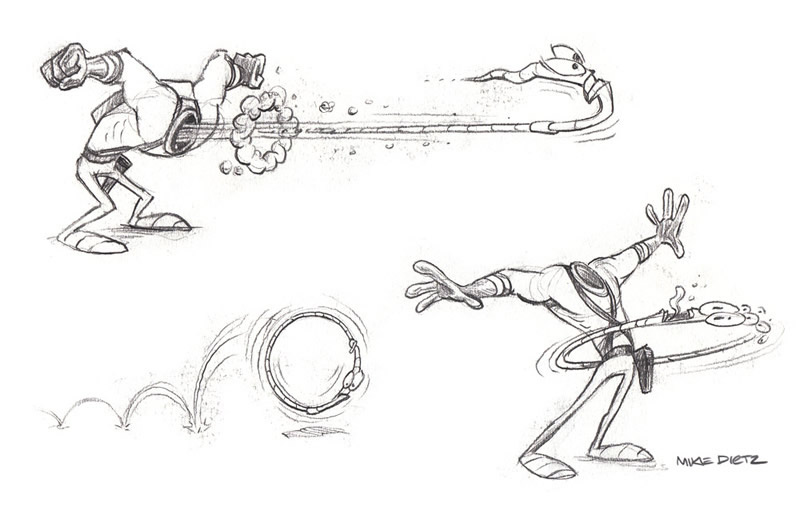

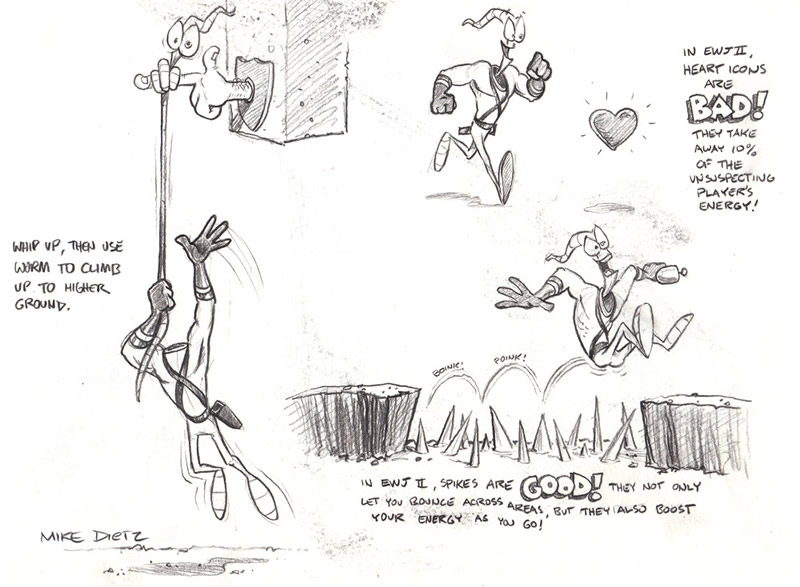

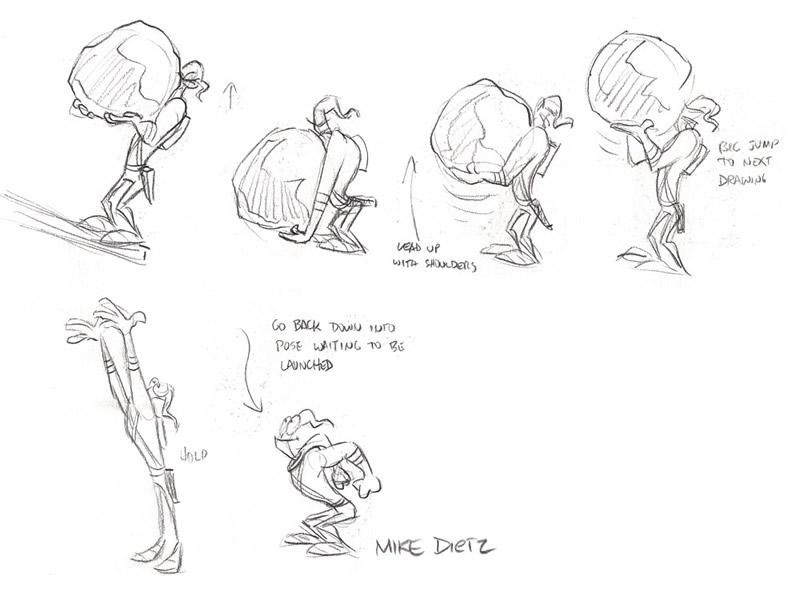

Click for larger images!

Sega-16: You worked on all three versions of Earthworm Jim on the Genesis and Sega CD. Were there any major leaps between the first and second games in regard to how you could animate?

Mike Dietz: We tweaked the animation technology slightly between EWJ and EWJ2, but nothing major. For me personally, the biggest leap was my drawing skills had improved significantly by the time we were working on EWJ2, so I felt I could get the actions across with a lot more clarity, personality and appeal. However, EWJ2 was a more difficult project because Doug and Ed left Shiny to start the Neverhood before the game was finished, so it was more of a scramble to get it done in time while still maintaining the quality of the animation I was shooting for.

Sega-16: Which version of Earthworm Jim do you prefer, the Genesis and SNES versions? Why?

Mike Dietz: I much prefer the Genesis version over the SNES, because the SNES was more limited than the Genesis in the number of sprites you could have on screen at any one time. Since our animation compression scheme was based on each frame of each character being constructed of multiple sprites, that meant the SNES version had less frames of animation and the size of individual frames was more limited, which meant we couldn’t stretch the character as much. So we would animate the characters first for the Genesis, and then we’d have to go back and selectively remove some frames and shrink down other frames for use on the SNES. The SNES did have better color palettes, so the character and background art looked better, but as an animator I liked the Genesis better because I had more frames of animation to work with.

Sega-16: Does anything added to the Sega CD Special Edition particularly stand out to you, such as something that wouldn’t fit in the cartridge original?

Mike Dietz: I really enjoyed the extended pencil test of Jim we put in at the start, which was animated entirely by Doug. We also expanded out the animation of the ending a bit for the Sega CD, but I thought the pencil test opening was funnier and a better value because everyone who played the game got to see it. I also liked the Big Bruty level that was added, mostly because it showcased some really nice animation Ed Schofield did on the creature.

Sega-16: You were a co-founder of the Neverhood, which never made any games for the Sega CD or 32X (or Saturn). Were there any plans for further supporting Sega’s hardware? Why the lack of support?

Mike Dietz: Hmm, how can I put this diplomatically? I thought the Genesis was the peak of Sega’s hardware, with the Sega CD being a nice addition, but it really only appealed to a small segment of their users. I loved my Sega CD, but there were only a couple of games I ever played on it, mostly Mickey Mania. I collect old game systems, and up until very recently I still had my Sega CD hooked up, but it finally stopped working a couple of months ago, so it looks like my days of playing Mickey Mania have finally come to an end.

Mike Dietz: Hmm, how can I put this diplomatically? I thought the Genesis was the peak of Sega’s hardware, with the Sega CD being a nice addition, but it really only appealed to a small segment of their users. I loved my Sega CD, but there were only a couple of games I ever played on it, mostly Mickey Mania. I collect old game systems, and up until very recently I still had my Sega CD hooked up, but it finally stopped working a couple of months ago, so it looks like my days of playing Mickey Mania have finally come to an end.

I felt the 32X was just stopgap hardware to extend the life of the console, and the Saturn just simply wasn’t a great platform. We moved away from game consoles for a year to develop the Neverhood on the PC, and by the time we returned to consoles for Skullmonkeys, the Playstation had established itself as the clear leader so that’s what our publisher wanted. The Genesis was my favorite platform to develop for, but unfortunately Sega was never able to repeat the success of that system.

Our thanks to Mr. Dietz for taking the time for this interview. For more images of Mike Dietz’s work, check out his blog.

Pingback: Mega Drive vs Super Nintendo Segundo os Desenvolvedores | Drive Your Mega