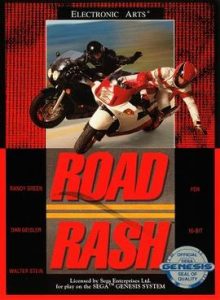

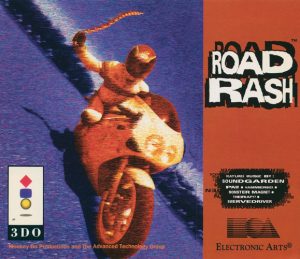

If you’re a Genesis fan, chances are you’ve played the Road Rash trilogy. It’s innovative combat mechanic combined terrifically with solid racing to deliver an experience unlike anything else on the console. The franchise was the brainchild of Electronic Arts Executive Producer and Creative Director Randy Breen, an industry veteran behind other EA hits like 688 Attack Sub and Ferrari Formula One. After finishing up the original Madden for computers, he conceived of the racing title that became Road Rash. It was a huge hit that spawned two sequels on the Genesis and further releases on the 3D0, Sega CD, Saturn, and PlayStation.

If you’re a Genesis fan, chances are you’ve played the Road Rash trilogy. It’s innovative combat mechanic combined terrifically with solid racing to deliver an experience unlike anything else on the console. The franchise was the brainchild of Electronic Arts Executive Producer and Creative Director Randy Breen, an industry veteran behind other EA hits like 688 Attack Sub and Ferrari Formula One. After finishing up the original Madden for computers, he conceived of the racing title that became Road Rash. It was a huge hit that spawned two sequels on the Genesis and further releases on the 3D0, Sega CD, Saturn, and PlayStation.

Breen was with Electronic Arts for 14 years, through its explosively creative period on console and its transition into an industry juggernaut. He would then move on to LucasArts, where he oversaw the release of the stellar Knights of the Old Republic and Mercenaries, before taking on executive and advisory roles at companies like Mediagraph, Outplay Entertainment, and Bright Star Studios. Currently, Breen runs his own consulting firm, where he serves as a tech executive, director, advisor, and business consultant for tech and entertainment companies.

Mr. Breen was kind enough to chat with us about his experiences at Electronic Arts and the creation of the Road Rash series.

Sega-16: You were at Electronic Arts from 1986 to 2000. Many consider that to be the company’s greatest period.

Randy Breen: It was when EA was a good place to be? It changed; you know… the company changed quite a lot in the ‘90s. The market had gone from being a hobbyist market to really becoming a real commercial enterprise. And, you know, in the late ‘80s, early ‘90s, nobody knew how it was going to work out. I mean, it was still wild, wild west.

Sega-16: I think that’s when it was best. From all the people I spoken to, it seems like that’s when they had the most fun.

Randy Breen: That was when we had the most fun. The early ‘90s, I’d say, was probably the best time to be there. But you know, at the same time, there wasn’t nearly as much money in it. So, even if we had success, it was nothing like it is now, the amount of money in the market.

Sega-16: I still play, but I prefer the older games because you finish a game today and you’ve got 20 minutes of credits – the development teams – 100 people long. And it kind of loses that mystique to me, compared to the games from the ‘80s and ‘90s where the teams were like four people.

Randy Breen: You know, I think that even when the teams got a little bit bigger, you could still carry a vision. I think as soon as you have departments of people and they all have to be coordinated in order to get something to work, that creates a lot more difficulty around getting everybody around the same idea. The other thing is, as soon as you have budgets that pay for all that, big companies get really risk averse. So, they don’t want to do things that are new. I mean, it’s completely contrary to how you would think about how to build something, how to create something interesting, right? When I think about how I like to approach a project, my interest in it is doing something new, you know? Not all of it’s new, but you’re trying to push the boundaries somewhere. Otherwise, it’s not very compelling. The problem with that is that that means risk, and that risk means that there’s a chance that it won’t work out or a chance that it’s late, or that it’s cost more to develop.

So, the idiom is that – and this is particularly true with the triple A publishers – in most of those cases, unless there’s a founder or somebody that is actually running the company that’s controlling the direction of the thing – and there are a few projects out there like that – unless it’s that kind of environment, the nature of it is usually to compare all the features that you’re thinking about developing and then rank them by difficulty or really, uncertainty until all the things that are most uncertain or most difficult get washed out because they basically create risk. So, I think that that’s why you see sequels. It’s really the main reason you see sequels, and sequels are not bad. It’s just that they get to a point where it becomes very hard to keep them interesting. You kind of get forced into repeating the same ideas and run into the problems that I’m talking about.

Sega-16: It’s the same thing you see with music when they talk about how artists hit the “sophomore slump.” Many of them hit that slump because they maybe had like, five years to perfect their first album and then it becomes a hit. Now, the label wants them to create another album of equal quality in nine months or something.

Randy Breen: That’s right. they want to schedule they can count on revenue. Movies are the same way. I think movies have gotten even worse, and that’s part of the reliance on comic book material for source. They’re able to leverage another property that’s already experimented with something and proven there’s an audience. And you know, that’s not altogether bad, but there’s a point where they’re going out of their way to only do those kinds of films because they think that they’re avoiding risk.

Sega-16: Like the Marvel movies. They think that every single one has to make a billion dollars. It’s like what happened with Batman vs. Superman. Warner Brothers was supposedly disappointed because it only made $870 million. Avengers hit the billion mark and they wanted to hit the billion mark too. The bar keeps getting higher and higher, so you have to have bigger studios and more people. It’s just harder to do all that and still keep that creative vision.

Randy Breen: You have to remember that to get to audiences that large, you’re spending massive amounts of money on marketing. This used to be true in the package games industry; I think it’s less true, although it’s still true for certain triple A titles like Call of Duty and so on. Basically, they have to get everybody to go to the theater at the same time, or they have to get everybody to be making purchases at the same time in order for them to realize those kind of numbers. The only way to do that is to spend… you know, they’re spending almost as much on marketing as they are to create the product, which is, in my view, obscene because the creation is really where the value is. If you’re really just spending just as much money on communication, I think there’s something wrong with that model. It’s really why I moved away from console coming out LucasArts. It was getting to the point where it was pretty clear there were 20 titles that were going to make money and everybody else was going to lose. Really, you know what at least half that list was known in advance because they’re all sequels or franchise titles. It just limited creativity around what you could do.

Randy Breen: You have to remember that to get to audiences that large, you’re spending massive amounts of money on marketing. This used to be true in the package games industry; I think it’s less true, although it’s still true for certain triple A titles like Call of Duty and so on. Basically, they have to get everybody to go to the theater at the same time, or they have to get everybody to be making purchases at the same time in order for them to realize those kind of numbers. The only way to do that is to spend… you know, they’re spending almost as much on marketing as they are to create the product, which is, in my view, obscene because the creation is really where the value is. If you’re really just spending just as much money on communication, I think there’s something wrong with that model. It’s really why I moved away from console coming out LucasArts. It was getting to the point where it was pretty clear there were 20 titles that were going to make money and everybody else was going to lose. Really, you know what at least half that list was known in advance because they’re all sequels or franchise titles. It just limited creativity around what you could do.

I think that since then, a number of channels have opened up. The PC has become a viable platform again, and there’s a lot of creativity there. Mobile became a real platform. That wasn’t previously the case. And digital distribution became a thing, which wasn’t really viable, at least on console at that time. I think that the result of all that is that the products that make the most money now are products they’re running as a service, which is a very different business model. It means that if you get a product that gets a following, then you can run it for quite a long time. This has been true with MMOs for a long time, but it’s true with a variety of other titles now, too.

Sega-16: I think like a game like Fortnite is example. If you mention it people roll their eyes, but just think about it from the business sense. My kids play Fortnite. This is a game that requires no manufacturing or distributions. It’s digital and it’s free to play. So, people can try it out and play it, and then they’re buying outfits for their characters that don’t affect the gameplay at all but they’re spending money.

Randy Breen: Somehow they turn that into seasons, right? I mean, when you think about the nature of those games, it doesn’t feel very seasonal. But what they’re doing is they’re creating a cycle. Once players get used to it, they start to anticipate things and it creates a routine draw. Fortnite’s an excellent example because its’ a title that really struggled before it came to market. When it was in beta, they were trying to figure out what it was going to be. It was up against Overwatch and some titles at the time that were dominating. They managed to figure it out. There are a lot of things inside of it that are really not necessary for a shooter, but I think that that’s what actually makes it sticky, ultimately. So, it’s an interesting one.

Sega-16: So, when it comes to Electronic Arts, you were there just as it became the company and they electronic cards that that like people who were playing console and PC games at the time came to know and love. When of I think Electronic Arts, I’m thinking Lakers vs Celtics and The NBA Playoffs, the original John Madden Football, Zany Golf…

Randy Breen: Yeah, so EA Sports became a thing. It was EA Sports Network for a little while and then they got sued by ESPN. I was there as that was being conceived. I actually worked on the first Madden. I was the producer that actually finished it. It was in development for five years.

Sega-16: The original PC version?

Randy Breen: Well, no. The original was actually an Apple II and then Commodore 64. And then I actually produced the PC version that came out after that. It was a sequel to the first one. So, it wasn’t identical to the first ones. And I mean, it was clear that that it was going to be a huge segment. You know, the fact was, though, it didn’t hold my interest because I knew that it just became a focus on getting a product out every year, revision in the engine every three years. But in between, you’re just updating the art or you’re changing the stats, and I just wasn’t very interested in that.

Sega-16: So, you weren’t involved in any of the others after that?

Randy Breen: Just the first two. And then the very first one, I came in at the very end just to get it finished. I was a young producer. So, I was just moving from a technical role into production. And it had been in development for quite a long time before I started.

Sega-16: Was this shortly after you joined Electronic Arts, or was there some time before you moved into game development?

Randy Breen: Well, the company started in, like, 1981, and I was in the Navy for the first part of the ‘80s. I came back to the Bay Area, coming out of the Navy. My, plan was to go back to school, and I came back to the Bay Area because I grew up out here. I was going to go to school out here. I put a résumé together thinking, “Okay, well, I’m going to get a job over the summer, organize myself. I’ll do that for a little while, and now get my schooling finished.” I literally went to a copy shop, Kinkos, which is how you got copies made at the time. The guy is making copies for me to hand out and he literally reads my résumé, and then tells me “Hey, I think somebody is going to want to hire you.” And, and that turned out to be Electronic Arts. EA had posted some job position at Kinkos on the bulletin board inside. It was for a junior technical role. And the thing is, I had a technical role in the Navy and I was also a hobbyist PC gamer, so I had my own PC, which was pretty rare at the time. One of the first games I bought was an EA product, but I didn’t make any connection between these things. I had no drive to go find EA and work for them. I just happened to buy one of their products when I bought my computer. Two weeks later, I was working for EA doing copy protection, setting up people’s computers, and building PC boards for an internal SDK. I was in heaven. I hadn’t really conceived that this was a job. I just happened to get lucky, and it connected my hobby and with my skill set at the time. So, I came in in this technical role, and within a little more than six months I moved into a production role as an assistant producer, then eventually graduated to an associate, then a producer, and then eventually an executive producer and creative director.

Sega-16: I love those stories. I mean, when I talk to like programmers and artists is like, there are a lot more “I saw an ad in the newspaper,” or “there was a flyer stuck to a telephone pole” stories than you think. It’s just amazing compared to today. Now, you have people who like, that’s their dream and they would do anything to get into the game industry. There was a time when you could almost just walk through the door all, “Hey, I’m here for the job.” The industry was just so much smaller back then.

Sega-16: I love those stories. I mean, when I talk to like programmers and artists is like, there are a lot more “I saw an ad in the newspaper,” or “there was a flyer stuck to a telephone pole” stories than you think. It’s just amazing compared to today. Now, you have people who like, that’s their dream and they would do anything to get into the game industry. There was a time when you could almost just walk through the door all, “Hey, I’m here for the job.” The industry was just so much smaller back then.

Randy Breen: There was no glamour in it, you know? My dad used to ask me if it was a real job. He couldn’t believe that this was something people got paid to do. There were a lot of programmers that were dropouts. And part of it was, you know, they would start doing coding on the side while they were in school, and then they were making so much money that it would just draw them out of school. I mean, I know of several guys that did exactly that. The other thing was that everybody in the industry was using coding languages that weren’t typically taught in the programming schools. In engineering, they were still teaching Fortran and Pascal. The best programmers were still coding in Assembly at the time, but then eventually it was C and C++. And, and those became draws for them to really focus their skills because they couldn’t go to school. And, you know, there were some schools that taught that stuff, but in a lot of cases they had to go through all of this foundational work to get to the thing they really wanted to learn, instead of just going out and starting to apply it. There was enough demand there that a lot of people were drawn out of school for that.

Sega-16: So, after you finish the Madden games, what was next for you?

Randy Breen: Well, so it’s not that simple. At the time, EA was a publisher. Think book publisher or record label; none of the work was done in house. All of the work was done by independent game studios that were anywhere from four people in a room, like you were talking about to maybe a dozen people. That was true in the 8-bit world, but really, EA’s focus was on PCs, not so much with consoles. They had a couple titles on Nintendo’s 8-bit console. They never really dealt with the Sega 8-bit machine. Internally, there was a lot of debate about whether EA would ever support Japanese consoles, because they didn’t like the business model.

And, and then the other issue was that Atari was such a collapse, you know? The game market was just scorched earth after it went away. And there were a couple of senior people at EA that were out of Atari. The issue is that in the packaged goods business, you have to build all your equipment. I mean, cartridges are hardware. It’s not like you’re just buying a floppy disk; you’re buying a circuit board. So, the cost of goods were very high for every product. And because it’s packaged goods, you have to sell them fast. It’s kind of self-fulfilling. You have to have enough product on the shelves to be able to fulfill demand quickly in order to get to a sales volume that causes that cycle to repeat enough that you sell into a large enough body of players so that you can rationalize all those costs. The issue is you have to build all of those in advance because it takes three or four months to actually build all of the stock to be able to put it on the shelves, which means that you’re carrying a lot of cost all the way to the time you get to the store. If it doesn’t sell, then what do you do with them? They can’t be replaced. That was what caused Atari to just destroy the market for a while because they had built this company up, and it kept selling more and more, but at some point they just got ahead of themselves. They don’t want to make more than they can actually get through the channel. You’ve probably heard some of the stories of that landfill with all of these games in it.

Well, that was context for Sega and Nintendo. That was what was keeping EA from moving into that model because the margin was small that the hardware manufacturer took a huge cut. I think that the preference was to focus on PCs because they looked like a more sustainable business model.

As I said, all of these games were developed by studios. Those studios would generally have an idea that they pitched, not unlike a writer would pitch a book. EA wasn’t the only one with this model, but EA would fund those developments and then help the team come to market, basically help figure out all the things to get the product made and provide services that they didn’t have – do the QA, handle the marketing, all the legal – there was a framework around all of the projects. As a producer, I was touching typically six or eight products at a time, at different stages of development. And so, John Madden Football was just one of the titles I was attached to early on. I did a couple of LucasArts products and Indianapolis 500, with Papyrus Design Group, who later went on to do all the NASCAR games. The list just goes on. I had done several of these driving games, both with DSI before they became EA Canada, and a game by Rick Koening called Ferrari Formula One, which was on the Amiga. That led me to be assigned to a skunkworks project inside EA to do a driving game for the Sega Genesis before the Genesis was going to come to the U.S. It was one of the first products that was done internally intentionally. Up to then, there were a few of these products that were kind of partly developed in house and partly developed at a house. I was on one of those called 688 Attack Sub, where John Ratcliffe really came in with a tech demo, and Paul Grace and I worked with John to conceive that product and get that built.

Road Rash was one of the first products that EA said, “Okay, we’re going to build this in house and it’s going to be an in-house title.” And there were a few, but that was one of them. At the time, they didn’t know what kind of driving game it was. I conceived the game and the motorcycle racing combat concept. I literally pitched it as Road Rash on Mulholland Drive and got the steering committee to sign off on that and then worked with the team to figure out what that product would be. It was a bit of a struggle for the first one, I have to say. The company wanted to show off all of its Sega titles at CES [Consumer Electronics Show] the year before they were coming to market, and we were still pretty early. We just started to get the tech to work. But CES is CES and the company wants to show things off. So, we had to show what we had, and basically, people were critical of it because it wasn’t meeting their expectations. Well, I’m telling them that it wasn’t ready to be shown. So, I had to convince them that we could figure out how to fix the things that needed to be addressed. I had confidence that we could do that, but I had to steer people, get people realigned on the project again, and we managed to get through that and solve some of the technical problems that we were having. Mainly, we were trying to get the frame rate up and trying to maintain the illusion that we had improved the animation and that sort of thing. I knew what needed to be done, and I managed to convince them to give us a shot. They did that, and the first title was launched and was successful, as were the other three games on Sega’s consoles.

Sega-16: So, Road Rash was in development for the Genesis before Electronic Arts became an official licensee?

Randy Breen: Well, I don’t know how much is public on that. There was a dispute between Sega and EA. Were you aware of that?

Sega-16: Yes, the whole reverse-engineering affair…

Randy Breen: Exactly. It was in development in the context of the reverse engineering, not knowing if we were going to be licensed. I mean, at the time, EA took the position that they didn’t need a license to do this if they were reverse engineered. They wanted to control their own titles, and that comes out of the PC publishing experience.

Sega-16: So, the issue was, “We’re making this this. The question is whether it will be licensed.”

Randy Breen: And it wasn’t the only one that was in that batch. The late ‘80s is when it started, and it was two years before the title actually shipped. But before we were done, we knew it was going to be an official Sega title. I think that at that CES I was talking about, they were presenting what they were going to launch. If I remember correctly, it still wasn’t clear whether it was going to be under their brand or if it was going to be a legitimate, Sega-licensed title. They were capable of doing it. They just came to terms with Sega and the rest is history.

Sega-16: How did you come up with the concept of having guys on motorcycles hit each other and fight. It all sounds really Mad Max-like.

Randy Breen: Well, sure. I think that Mad Max is definitely a reference. I actually cobbled together some video material in the presentation for the first pitch. I pulled together some material from Akira, the anime movie, and I pulled together some footage from Grand Prix motorcycle racing where a couple of racers were basically elbowing each other down the straightaway because they were vying for position to approach a corner. I had been working on these racing titles. I enjoyed them; I like racing. I’m not racing now, but I was a club racer on motorcycles. I like the discipline of it, but not everybody does. Going around a race track, you have to like going over and over, refining your approach to turns, getting your timing right in every little place to eek out better times progressively. That’s interesting to me, but it’s not interesting to a lot of people. It doesn’t hold their attention. So, I was interested in something that was entertaining but still had that element of racing, where racing was the clear motive and you were still trying to win. Some of the references I had at the time… There were a number of these car games where you could shoot at each other while you’re driving, and that didn’t seem that compelling to me, so I gravitated towards something that was more realistic.

I’m trying to describe these touch points, and I think for me it all came together in this idea that you could take that nudging down the straightaway and amplify it – put it on public roads and you start to have something that is dramatic, cool, and potentially funny. There was a certain slapstick element to crashing that was intentional. The fact that you had to run back to your bike – there was a time penalty, but it didn’t set you back so much that you couldn’t catch back up. There were things in there that were intentionally trying to have a little more realistic element to it and still be entertaining.

There’s one other thing I’ll mention. When I was in the Navy I did quite a lot of traveling around the Pacific. On one of those trips I went to Japan and took a tour up into the mountains. During that tour, I really witnessed these bike groups, in full leathers and on race bikes, for the first time. I had never seen anything like that. It turns out there was an analogue to that here in the Bay Area. There’s a heritage in the Bay Area; some famous racers came out of this area. Kenny Roberts, who is considered one of the greatest of all time, has a ranch out in Modesto. The guys who built his flat track bikes have been down in San Carlos for years. So, there was a certain culture of that here too, and I was exposed to that after I got out of the Navy. The culture around that was one of the elements that made its way into the game as well.

Sega-16: When you pitched Road Rash, what kind of reception did you get? When you showed them this game with people hitting each other and fighting on motorcycles, was there any resistance to a game with that kind of violence?

Sega-16: When you pitched Road Rash, what kind of reception did you get? When you showed them this game with people hitting each other and fighting on motorcycles, was there any resistance to a game with that kind of violence?

Randy Breen: We were very careful not to express the violence in a way that was gory or over-the-top. If anything, it was really pretty dampened. Every time you crashed the bike, for example, you got back up and ran back to it. But even in that first pitch, I was describing this idea that the crashes were exaggerated and part of the entertainment value. Some of the feedback I got after we finished the project, people would talk about laughing about some of the situations they would get into because the nature of the gameplay was concentrating on what’s coming down the road, but then there’s something beside you that you have to pay attention to. That’s what takes your attention away from what you’re doing down the road. So, it’s this context switching between these two things that actually made the game work.

Sega-16: I remember playing Road Rash when it came out. I had played racing games on my Master System and Genesis and in the arcade, but I had never played a game like that, where you could use chains and nightsticks and things like that. I was in high school at the time, but I can still remember renting the game and my friends I sitting in my room playing. We had never played a game like that. Even my friends who weren’t racing fans enjoyed it because it had that different element to it.

Randy Breen: And that’s what we were going for, for sure, to try and get the racing fans and a wider audience.

Sega-16: It was really different, and it stood out. I think it still sticks out today, and I’m surprised that the formula hasn’t been copied more. You had early racing games, like Pole Position and then later Formula One games came out, and it one comes out and is a hit, other companies tend to copy it. The Genesis and SNES didn’t have the bunch of clones you might expect for a game that was so successful. Road Rash seemed to be different, though. It wasn’t something that you could just copy.

Randy Breen: It would almost be too overt to just copy it. The interesting thing is that after I left EA, they tried to reform the franchise. At least three times with different teams and couldn’t get it together. Part of it is that it is complicated. You can’t really just pigeon hole it in the same way you can other things. I think that those kinds of projects require somebody on them that is really holding the vision together and getting the team behind them because otherwise, they don’t know what they’re making. Some things are culturally consistent enough that most people on the team can visualize what it is they’re doing. If there aren’t a lot of other examples for that, I think it makes it more challenging.

Sega-16: I agree. So, you did the three games on the Genesis and then the newer consoles came out, like the 3D0 and the Atari Jaguar… Sega had the Sega CD… Tell us about that version of Road Rash.

Randy Breen: It was kind of a hybrid. Even the third game on the Genesis was kind of a hybrid. I was managing Road Rash III but kind of got drawn over. They had started the 3D0 project and really got the technical foundation together. At the time, they didn’t want me on that project because they wanted me to make sure that I could get the Genesis product delivered because that was where the revenue was. At the same time, I was trying to advise them, kind of on the side. It got to a point where they really needed a more complete view of what the product needed to be to really differentiate itself. It was important at the time because you had a CD and had to justify what was different about the platform over the 16-bit consoles. The most significant difference was the disk, but there was no clear plan about what to put on it other than just the game content and it didn’t need the disk to do that. It just wasn’t that much memory.

I started working with the team more directly , and we came up with a content plan. I also started to unify some of the assets, so there was an opportunity to do that with the video for the Sega CD, obviously, because we could share the video. That distributed the cost across two platforms so it made it more viable for both of them. We also started looking at the animation, and we had this rotoscoping (the process of manually altering film footage one frame at a time) planned for the 3D0 and we could use that for the Genesis as well, as a derivative. It was a way to update some of the graphics in the game and reuse the content from the higher-end version, basically down-rezing it.

Sega-16: From the 3D0 to the Genesis or to the Sega CD?

Randy Breen: At this point, it’s hard for me to be specific because it’s been too long, but we started to share content between the two is the main thing. The 3D0 gave us an ability to kind of pick and choose some of those assets and apply them to the Sega CD.

Sega-16: So that game was developed for the 3D0 first?

Randy Breen: The video content was developed for the 3D0 first, and it made its way down to the Sega CD.

Sega-16: And then it was later ported to the Saturn and PlayStation.

Randy Breen: Yes, and the PlayStation one in particular was derivative directly from the 3D0.

Randy Breen: Yes, and the PlayStation one in particular was derivative directly from the 3D0.

Sega-16: You mentioned that there were two attempts to revive the series after you left…

Randy Breen: One was just before I was leaving. They had already started it, but I already had plans elsewhere. I know that there was at least one other after I left… I think two. Then after that, I had conversations with them a couple of times about restarting but they never amounted to anything.

Sega-16: I know EA had no love for the Dreamcast, but do you know if there were ever any ideas floated about bringing the series there?

Randy Breen: I don’t remember the Dreamcast specifically being part of that. EA was never a huge supporter of the Dreamcast anyway. By the time the PlayStation 2 came out, it was pretty clear that it was going to be the Xbox and PlayStation, and the Dreamcast was kind of an odd man out. Anything that’s too different means you have to take more resources to serve the market. That means that the audience has to be large enough to justify whatever that cost is. And it’s not just the money. You have finite resources and you’re trying to figure out, “how many things can I do? Does it make sense to spend time on that or build another PlayStation product?”

Sega-16: I love the Genesis trilogy and the Sega CD version, and I’ve been one of those people wondering when we’re going to see another Road Rash game.

Randy Breen: Yeah, it’s a bit sad. You know, the other things that’s interesting about the title – particularly the Genesis period, the early ‘90s – is that it was EA’s most profitable franchise. It didn’t sell the most, but it was the most profitable because it was original IP. Nuclear Strike was another one. There were a couple of original titles developed inside EA (Nuclear Strike was partly developed outside, so it was a little bit different), and the fact that Road Rash was internal IP meant that there was no license on it. So, it was the most profitable at the time.

I was a strong advocate for continuing to develop original titles, and I came into EA at a time when there were a lot of them published. The reason for that was because it was a new market, and it was almost necessary to produce new titles because there weren’t that many things to franchise. We did sequels when there was success, but there was still a lot of opportunity to build new ideas. Gradually, EA got more and more conservative, and I would argue that some of that came out of the sports business. They just got into a mode of producing a sports game every year, so it’s guaranteed revenue each year and they’re paying high license fees. It’s reliable revenue, and the bigger the company got the more attractive that reliable revenue became and the more risk-averse it became as the cost of the titles got larger. Those things really started to limit the kinds of things that could be done, not just for EA; any of the big studios are like this. Obviously, there are exceptions, and there were new properties that were launched, but it became harder and harder to do it.

Our thanks to Mr. Breen for taking the time for this interview.

Pingback: Road Rash: EA’s Riskiest Game Ever Made - Retro Gaming Geek