It takes a lot to endure in the video game industry. Constant studio closures and mergers can end careers almost before they truly begin. The 1990s was a period that saw several major upheavals as the industry transitioned from 16-bit, cartridge-based consoles to 32-bit CD-ROM monsters like the PlayStation and Saturn.

It takes a lot to endure in the video game industry. Constant studio closures and mergers can end careers almost before they truly begin. The 1990s was a period that saw several major upheavals as the industry transitioned from 16-bit, cartridge-based consoles to 32-bit CD-ROM monsters like the PlayStation and Saturn.

Mike Arkin saw all of it. From his start as one of the first employees at Acclaim to stints at Sony Imagesoft and Fox Interactive, he produced titles on several Sega consoles. Through all the changes that rocked gaming during the decade, he carved out a career that spanned several major publishers and more than a few high-profile projects.

Sega-16 recently spoke to Mr. Arkin about his career in gaming and his work on games for Sega’s machines.

Sega-16: Acclaim was where you got your start in video games?

Mike Arkin: Yeah, I was the seventh employee. I just kind of wandered in off the street and said, “You know, I want to work here,” and then they hired me. The joke was that I was the first person there that knew how to use the controller. They were making games but just put them in the box and shipped them. I was the first one who could actually play the games that they were making, which was kind of crazy.

Sega-16: What was the environment there like so early on? Acclaim went on to become this huge company.

Mike Arkin: It was indescribable because the success was instantaneous. At that time with the NES, you could buy a game from Japan, probably for nothing, and ship it in the U.S. and ship five million copies at 50 bucks. So, do the math on that. They were just making a tremendous amount of money, and it was so easy. The environment was amazing. There was no pressure. It wasn’t like, “Hurry! Hurry! Hurry!” or, “Oh my god! We’re struggling to survive.” It was like, “Hey, we made 100 million dollars last month. We should have a giant party!” We had black-tie Christmas parties, and I rented a tux. I was 18, but there was money. I think somebody probably said, “If you can’t afford it, we’ll get you a tux if you need it.” You didn’t even think about money because there was so much success, and the office was just, like, a house. It was this two-story wood house, and it was family, you know? It was a crazy time. The world will never be like that again.

Mike Arkin: It was indescribable because the success was instantaneous. At that time with the NES, you could buy a game from Japan, probably for nothing, and ship it in the U.S. and ship five million copies at 50 bucks. So, do the math on that. They were just making a tremendous amount of money, and it was so easy. The environment was amazing. There was no pressure. It wasn’t like, “Hurry! Hurry! Hurry!” or, “Oh my god! We’re struggling to survive.” It was like, “Hey, we made 100 million dollars last month. We should have a giant party!” We had black-tie Christmas parties, and I rented a tux. I was 18, but there was money. I think somebody probably said, “If you can’t afford it, we’ll get you a tux if you need it.” You didn’t even think about money because there was so much success, and the office was just, like, a house. It was this two-story wood house, and it was family, you know? It was a crazy time. The world will never be like that again.

Sega-16: I’ve heard similar stories from companies like Electronic Arts. They had NERF gun battles on Friday in the office and things like that, and Atari with the Jacuzzi meetings…

Mike Arkin: We didn’t have Jacuzzi meetings, but they took the whole company to Jamaica. If you’ve ever been to Jamaica, you know everybody has a lot of pot, so there was a lot of that going on. All of a sudden, that was a five-day weekend for the company. They took everybody – girlfriends, part-timers – everybody went to Jamaica, and they paid for everything because there was so much money. We didn’t have NERF guns, but we went to Jamaica. There was also this thing called “Pizza Friday” where they’d bring in pizza for everybody. It started with like, two pizzas, and then a few years later it was 50 pizzas as the company grew. Then we had “Birthday Thursday” in which they would just open a tab at the bar across the street. There was a British pub, and somebody would just put a credit card down and everybody could just drink until 2:00 a.m. or whatever. We’d order food; nobody cared. I’d say, “Can I order food?” and they would be like, “Yeah. Who cares? Nobody’s going to complain about the money.” There was so much money. It was ridiculous. So yeah, it was crazy. I made like, 25k a year or something, but the world was different back then, too. There was nothing to spend money on. It wasn’t like now where you have to have all these gadgets and things. None of that existed. I had a TV and a Nintendo, and I was happy.

Also, when I was at Acclaim, we had this very long relationship with Midway. I was very young and didn’t really know much about the world, but I’d go up there three or four times a year in Chicago and the guy that I met with was a guy named Roger Sharpe. I didn’t know who he was.

Sega-16: He handled licensing.

Mike Arkin: Yeah. He was just this cool dude. We basically had this deal that allowed us to do home versions of all the Midway arcade games. It was like, a 10- or 15-year deal or something. They’d just send us every machine, and we’d just play them and figure out which ones we wanted to do. Literally in the last couple of months, a friend of mine was talking to me about how Roger was this incredibly influential master of pinball, and there was a documentary about him.

Sega-16: Oh yeah.

Mike Arkin: He helped to change the laws and all that, but apparently, he just was an amazing pinball player, and I had no idea. He was just some guy I used to meet, right? I didn’t know that years later he would be famous.

Sega-16: He actually designed a few games. There’s one called Sharpshooter. I think that was in the documentary. His kids are professional pinball players too.

Mike Arkin: Oh yeah, I think that was mentioned in the documentary. So, it was cool and like I said, we’d play all their games, and it was the coolest thing. They’d send us one of everything, so we did home versions of everything. There were some later ones that we didn’t do, but the office downstairs where I was, it was an arcade. We were constantly trying to find space, like, “Where do we put another one of these things?” It was like, “Mortal Kombat 3? We already have two of those!”

Sega-16: That’s a great problem to have!

Mike Arkin: It’s a great problem to have, but I think also I think it was something we didn’t mind making space for because it was a perk to have all these cool arcade machines. It’s a whole different thing. In the early ‘90s or even late ‘80s, arcade machines were still special. Today, your PlayStation 5 is better than most arcade hardware, so it’s just not as cool as it was. Even when Mortal Kombat came out on Super Nintendo and Genesis it was a big deal. It’s like, “Oh my god! I can play this arcade machine at home!” Kids… their minds were blown. Today, it’s just normal, right? I mean, kids today don’t have the arcade experience like I did when I was a kid.

Sega-16: Yeah, I tell my kids that, about what it was like to go to an arcade and see this great game and then wonder, “Is this going to come to the Genesis?”

Mike Arkin: Right. I didn’t even think that. It was like playing Asteroids or Battlezone or something. It was an arcade experience. You didn’t even imagine that it was something you could have played at home; that just didn’t exist at that time. Even Mortal Kombat. It’s like, “Play it at home? What are you talking about?”

Sega-16: That whole social environment’s gone. You have online play, but it’s not the same thing.

Mike Arkin: Yeah. I mean, this is a whole different story. When I was in high school, you’d go out and you’d just hang out with your friends. “Let’s go to the arcade,” or where I grew up in New York. In the area where I lived uptown, there were no arcades, but there were a couple of stores that had two or three machines each. It was like, “Let’s go to the pizza place. They have Dragon Lair. We’ll play Dragon’s Lair for a bit,” or, “They’ve got Battlezone at this other place.”

Sega-16: I grew up on Long Island, and I remember on Sundays my brother, friends, and I used to walk to the opposite side of town just to get to one pharmacy that was open because they had Donkey Kong.

Mike Arkin: Yeah. My mom lived on Long Island, actually. I remember we’d walk, take our bikes, or whatever to the roller-skating rink that had like, 20 arcade machines. I think there was an arcade too, actually. I mean, that’s a part of culture that just doesn’t exist anymore. First of all, I can’t imagine letting my kids just go for a walk somewhere. Like, what are you talking about? You’re not armed!

Mike Arkin: Yeah. My mom lived on Long Island, actually. I remember we’d walk, take our bikes, or whatever to the roller-skating rink that had like, 20 arcade machines. I think there was an arcade too, actually. I mean, that’s a part of culture that just doesn’t exist anymore. First of all, I can’t imagine letting my kids just go for a walk somewhere. Like, what are you talking about? You’re not armed!

Sega-16: At Acclaim, you produced several Game Gear versions of titles that came out on Genesis. What was Acclaim’s attitude towards the Game Gear? Was it secondary, or was it considered an equal to the Genesis?

Mike Arkin: If you look at their list of games, it’s a lot of TV, movies, or comic book stuff. It was definitely Acclaim’s philosophy that there was always a license, and I think that what they wanted to do was make a game and make as much money as they could. So, it was NES, SNES, and Genesis. I don’t think we did Master System, but we did Game Gear because Game Gear was selling okay. There was money to be made there. I think that what we would do is go to a developer that would do all of them at once. I think a lot of times, the NES game would be ported to Game Gear because they were very similar in terms of graphics. So, it wasn’t like we were taking, like the Genesis, and porting that to Game Gear, and it really was just like a kind of multi-platform strategy that you don’t really have today. You can do three platforms, right? You can do Sony, Nintendo, and Xbox, but back then you could literally have one game and you could have six platforms. We never did TurboGrafx-16 or the handheld Turbo Express. We didn’t do any of that, but there were some games I worked on where we’d have NES, SNES, Genesis, Game Gear, and… I’m trying to think if there was something else. I guess maybe it was just those four. I think maybe there was the Master System. I’m not sure I don’t remember since it was so long ago.

Sega-16: There was the Game Boy as well.

Mike Arkin: Game Boy, right. That was the fifth one. I think it was because Game Gear was way more sophisticated than a Game Boy because it was full color, so I think it was either the Genesis or it was the NES that got ported to Game Gear. I think I probably worked on five or six of those.

Sega-16: Did you ever have any original titles under consideration?

Mike Arkin: Acclaim did very little of that. There was a time during the NES that we did one or two. That was when with the NES, you could make money with any game; it didn’t matter what it was. I think later on, as we grew in the Genesis and SNES era, I don’t think we did anything that wasn’t a license. I can remember because at that time, if you had the Simpsons, you’d sell 10 times more. Obviously, there were companies like Konami that would do your Metal Gear, or your Contra, or something like that, and those were original IP, but it just wasn’t Acclaim’s thing. It wasn’t something they were good at. I could see there were definitely companies that made a lot of good original IP, but Acclaim just didn’t do that.

I often wonder, years later, if Acclaim had made a couple of games where they said, “These games are going to be quality, not just original IP, but it’s got to be a 9 out of 10.” Could that have taken Acclaim to the next level at some point where they transitioned to making original IP and games that were of higher quality? There were always licenses, and they weren’t high-quality games. They were generally lower-quality games. We did Total Recall, and we had to make that game in seven or eight months. So, that’s not going to be an A+ game. It was actually reviewed as one of the worst NES games of all time, but you’re trying to make the movie, right? You need to get it on the shelf before the movie comes and goes. But Acclaim, that just wasn’t something we did.

Sega-16: What made you decide to leave Acclaim?

Mike Arkin: I got fired! So, that choice was made for me. I was super young. I was super immature. I’d never really had a job before, and I never really learned how to be a good employee or a good person. I also never had any mentorship because of the way it worked at Acclaim. The person who I worked for was not really a very good person, so if anything, what I learned from him was bad habits. He was kind of a mean person, so at some point, people just didn’t want to work with me, and they told me to take off.

I was lucky because I had at the time, been having a discussion with someone at Sony Imagesoft. I had a month off, and then they literally just called me and said, “Hey, remember we talked to you like, three months ago? Suddenly, we really need someone to fill that position.” I was like, “Oh, well I’m available!” It was just a great coincidence, and if you’re ever going to move literally from one side of the country to the other, the best way to do it is to have Sony pay for it. I was 22 or something, and I could barely balance my checkbook. Sony put all my stuff on a truck, and they drove my car onto the truck and basically said, “Your stuff will be there in a month” and then put me in a hotel, so it was awesome. It was great.

Sega-16: At Sony Imagesoft you did some projects on the Sega CD. I know you’ve mentioned that some of them hadn’t been released.

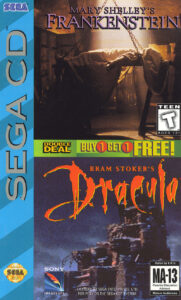

Mike Arkin: When I got there, I got a lot of leftovers. Some projects had shuffled, and then they had some things that needed some help. I ended up with two Psygnosis projects, and they were both Sony movies. Sony was trying to capitalize on the fact that they had the game studio and the movie studio. They had this development team, Psygnosis, in the U.K., so the idea was to put that all together. They had Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which I believe was Robert De Niro. I can’t remember if he was the doctor or the monster.

Sega-16: The monster.

Mike Arkin: Okay. It was so long ago that I barely remember the movie. There was another movie with Ray Liotta called No Escape, which was about a prison island. I used to joke that there was not one woman in this movie! What guy is going to want to see it? Every movie needs to have the heroine, right? It wasn’t a bad movie, but the game wasn’t great. Basically, they made both games at the same time. I think there was some crossover in terms of the tech, and I will give the team some credit. Those were designed as Sega CD games, so it wasn’t a Genesis game that they just threw on the Sega CD. They were designed with the CD in mind: bigger worlds and streaming tech. I think Frankenstein shipped. By this point, the Sega CD is not a big success and Sony’s trying to figure out how to cut their losses. So, they put that in a two-pack with Dracula, which was like one of their earlier Sega CD games, so that did ship. I have one on a shelf somewhere. It kills me that No Escape didn’t ship. At the end of it, I think marketing gave me one of the mock-up boxes, which was just art in the plastic. I had a burned disc in the thing, and I swear it was on a shelf somewhere, but I haven’t seen it for years. Recently, it’s occurred to me that I might have the only copy of the game, and that might be historical.

Mike Arkin: Okay. It was so long ago that I barely remember the movie. There was another movie with Ray Liotta called No Escape, which was about a prison island. I used to joke that there was not one woman in this movie! What guy is going to want to see it? Every movie needs to have the heroine, right? It wasn’t a bad movie, but the game wasn’t great. Basically, they made both games at the same time. I think there was some crossover in terms of the tech, and I will give the team some credit. Those were designed as Sega CD games, so it wasn’t a Genesis game that they just threw on the Sega CD. They were designed with the CD in mind: bigger worlds and streaming tech. I think Frankenstein shipped. By this point, the Sega CD is not a big success and Sony’s trying to figure out how to cut their losses. So, they put that in a two-pack with Dracula, which was like one of their earlier Sega CD games, so that did ship. I have one on a shelf somewhere. It kills me that No Escape didn’t ship. At the end of it, I think marketing gave me one of the mock-up boxes, which was just art in the plastic. I had a burned disc in the thing, and I swear it was on a shelf somewhere, but I haven’t seen it for years. Recently, it’s occurred to me that I might have the only copy of the game, and that might be historical.

Sega-16: I can connect you to people, like the preservationists at the Video Game History Foundation, who would be very interested in preserving it.

Mike Arkin: Well, I literally can’t find it. I’ve been looking for it. I know I had it at one point. I can’t imagine throwing it away. I don’t usually throw things away, but I did have one copy of this No Escape game. Actually, I live in Frisco, right around the corner from the National Video Game Museum, and those guys are always begging me to bring in some of the stuff I have. I have a Mortal Kombat cartridge. It’s like Mortal Kombat 1.5 where you play as Goro, and I may have the only one of those, so they want me to come in so they can rip it before the bits rot. One day…

So, I worked on those two and then I took off and I went to Fox.

Sega-16: That’s where you produced games like Die Hard Trilogy and Independence Day. I know both came out for the Sega Saturn as well as the PlayStation. How different was the development of those games? Were there separate teams or one for both?

Mike Arkin: In both games, it was one team. Die Hard was a little bit different because there was a core team that was doing the PlayStation version, and then there were like, two guys or something that were porting it to Saturn basically at the same time. Saturn had its challenges, but they were simple for the time, right? They weren’t super advanced game engines or anything like that. So, I think it wasn’t a big problem to get them running on Saturn. I’m sure you’ve heard the stories about how the Saturn was pretty hard to develop for, and you know the main reason was that there were just so many different processors in the box, and you had to basically write code for each one of them, so it was a bit of work.

Sega-16: I spoke to David Warhol from Real Time Associates (Bug!, Bug Too!) and they just got so frustrated that they just basically shut off the second processor. The first Bug! game didn’t use it at all.

Mike Arkin: I think that’s almost a typical story about engineering. If you over-design something, you run the risk that people just won’t do it right. What you just described was not uncommon for Saturn because if you had to make a game in a hurry, the easiest way to do it would be just to use one CPU. We’d just shoehorn everything onto the main CPU and not worry about it. PlayStation 2 had a similar problem where you had two co-processors, and I think there’s somebody who did some analysis once where they said something like 60 percent of games didn’t use the second co-processor because it was just too much trouble. So, it was kind of how they were designed. It was really easy for the CPU to throw stuff to that first co-processor, but then the second co-processor worked a little bit differently. The more advanced teams would use everything right and use them both, but it was just more work and it’s like, “Yeah, we’re going to make a game in a year. Maybe I want to focus on making the game and not writing a bunch of engine code,” but that was a big problem with the Saturn for sure.

Sega-16: I saw that there was also a console Alien vs Predator game that was not released. Was that the same as the PC version, or was it a different project?

Mike Arkin: It was basically that project on PC, PlayStation, and Saturn; and I think during development the team was having a real hard time. I think at some point they were like, “We’re not sure if we’re going to be able to get this to run on a PlayStation,” and Saturn was a little bit technically below the PlayStation. So, it couldn’t work on PlayStation, and I think at some point, the decision was made – I think that might have been before I left, or after I left. I’m not sure – at some point it was just like, “Hey, let’s just focus on PC” because I do remember seeing it.

Sega-16: My introduction to Alien vs Predator was on the Jaguar, and I loved that game. So, when I saw the news that there was one in development for PC, it was like, “Oh great! It’ll come out for the Saturn for the PlayStation!” In 1995 or so, it wasn’t like today, when everybody has a computer, and our phones are super advanced. Back then, I used to have to go to the university just to use the Internet. No one I knew had a PC. If it came out for PC that meant, “Nope I’m not going to be able to play it because I don’t have a PC.”

Mike Arkin: I think Saturn was starting to kind of reach the end of its life at that point. I don’t remember exactly what year that happened, but I do know that there was a point where we realized that PlayStation was winning. I think that PlayStation and Saturn were not, in some ways, just like SNES and Genesis. Clearly, Saturn was the inferior hardware, and Sega would sit there and argue with you. “Oh no, it has more gigaflops!” or whatever. The problem was that it was about the ease of accessing that hardware. So, if you used every CPU in sync and you really worked the hardware, then yeah, it was slightly more powerful than a PlayStation 1. On the PlayStation 1, you just wrote in C language and compiled it, and it was a single CPU. The GPU worked on its own, and you didn’t have to write specialized code because it was all done through an API [application programming interface], so you could very easily just do work on PlayStation. It just worked compared to Saturn. You could get that power, but it was 10 times the work.

Mike Arkin: I think Saturn was starting to kind of reach the end of its life at that point. I don’t remember exactly what year that happened, but I do know that there was a point where we realized that PlayStation was winning. I think that PlayStation and Saturn were not, in some ways, just like SNES and Genesis. Clearly, Saturn was the inferior hardware, and Sega would sit there and argue with you. “Oh no, it has more gigaflops!” or whatever. The problem was that it was about the ease of accessing that hardware. So, if you used every CPU in sync and you really worked the hardware, then yeah, it was slightly more powerful than a PlayStation 1. On the PlayStation 1, you just wrote in C language and compiled it, and it was a single CPU. The GPU worked on its own, and you didn’t have to write specialized code because it was all done through an API [application programming interface], so you could very easily just do work on PlayStation. It just worked compared to Saturn. You could get that power, but it was 10 times the work.

Sega-16: I believe Saturn games were still done in Assembly language.

Mike Arkin: Right. Like I said, there were so many different processors on the machine. There was an audio processor you had to write, and those things were microcode that you had to write. I think what people started to do was things like, “Hey, we’ve got this powerful processor for the sound,” but it was like a Z80 or something. It was full of power. People were like, “Forget the sound. We’re going to run AI on it,” or something like that. I mean, there were lots of tricks that you could do, but again, in a cross-platform environment you just want to do what’s easiest, what’s the common denominator across three pieces of hardware, including PC. The more complicated machine is always going to be the one that people say, “We don’t have time for that.” That’s why first-party games always look better, right? They can focus on a single piece of hardware. If we’re just trying to make Diehard on three systems, the last thing anybody wants to do is say, “Oh, we’re going to spend an extra six months,” or maybe it’s, “Hey, we need two more engineers. We’re going to write Assembly code for all these different processors.” Nobody wants to do that work.

Sega-16: Plus, the added development costs…

Mike Arkin: Right. When I say, “Do the work,” what I mean is the extra cost. I think players don’t realize everything has a cost and game development is risky. A lot of the time it’s not the people doing the work but someone upstairs somewhere that has to write the check, and sometimes they say no.

Sega-16: After Fox, your next stop was Activision, correct?

Mike Arkin: Yeah, I produced a game called Battlezone that was PC only, although as I was leaving, we did a licensing deal for N64 Battlezone to Crave, and that was how I met Crave Entertainment.

Sega-16: Crave went in big on Dreamcast.

Mike Arkin: Yeah. I guess it was just that it was new hardware. Crave was trying to find their niche, so they saw that as the next big thing, and they really went pretty deep into Dreamcast. I think we must have shipped like, 20 Dreamcast games.

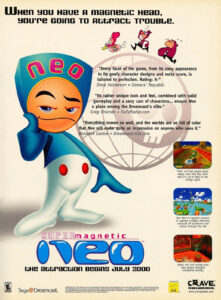

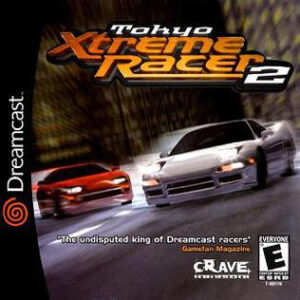

Sega-16: I don’t recall if I ever played a Crave game before that, but the first time I really took notice of the company was when I got my Dreamcast and got a game called Super Magnetic Neo, which was a platformer. I had that and Tokyo Xtreme Racers. Crave was really supportive of the Dreamcast. What did you think of that hardware?

Mike Arkin: We thought it was the greatest thing in the world at that time. It was the first 128-bit console, and we were looking at that and going, “Wow! Look at these graphics! This looks great!” It was interesting because they kind of jumped ahead of everybody else in terms of the life cycle. I think it was between PlayStation 1 and PlayStation 2. Sega was kind of cool, right? Even though it was a Japanese company, they had this big American organization, so you were dealing with these American personalities. The Japanese were very serious and dry, and these guys were just like rock stars. They had fun parties, and it was a cool thing to do.

I think there were just a lot of great games. That was the other thing, right? I remember when the hardware first shipped, and we were playing PlayStation 1, which was so polygonal. Tomb Raider on PlayStation 1 was so super blocky, and then Dreamcast came out, and it just blew our mind, having high poly characters for the first time. In retrospect, if I played it today, I’d probably laugh at how crappy the characters look. You mentioned Tokyo Xtreme Racer. That game came out, and we couldn’t believe it. The cars were smooth and shiny. We’d never seen shiny before. I mean, the cars in Gran Turismo were shiny, but it was low poly there were no shaders or anything, so it was single textures for everything. I think Dreamcast let us do specular maps and stuff like that. We’re doing multi-texturing for the first time, and it was incredible. Again, if I looked at those games today, I’d probably laugh, but we thought we were living in the future.

Sega-16: Do you have a favorite of the projects you worked on?

Mike Arkin: It’s probably Tokyo Xtreme Racer, the whole franchise because I think I worked on three or four of those. Super Magnetic Neo was definitely the quirkiest game I’ve ever worked on.

Sega-16: You worked on Super Magnetic Neo?

Mike Arkin: It was a Japanese game, so it was basically a finished game. We had Genki, which did Tokyo Xtreme Racer, the same team. It was one of those weird deals where you couldn’t really change much.

Sega-16: You just localized it; that’s really all you could do.

Mike Arkin: Yeah, we localized it. I don’t think there was that much text either, but it was just a really weird game. I remember playing it and just being like, “I can’t even play this; this is so weird.” With Tokyo Xtreme Racer, I rewrote all of the text because I like cars, so it was a game that I would have bought and played even if I didn’t work there. They would translate everything into English for us, and they would be really bad translations. Then, I would sit and kind of rewrite it all. It was hard because it was car parts, and sometimes I wasn’t quite sure what they were trying to say because there are some English terms that they use in Japan that don’t directly translate to English. It would be a typical Japanese term for a suspension part or something, but I didn’t really know what the English equivalent of that was, so I was just making stuff up in some cases. It was hard because sometimes Japanese doesn’t translate one-to-one to English.

Mike Arkin: Yeah, we localized it. I don’t think there was that much text either, but it was just a really weird game. I remember playing it and just being like, “I can’t even play this; this is so weird.” With Tokyo Xtreme Racer, I rewrote all of the text because I like cars, so it was a game that I would have bought and played even if I didn’t work there. They would translate everything into English for us, and they would be really bad translations. Then, I would sit and kind of rewrite it all. It was hard because it was car parts, and sometimes I wasn’t quite sure what they were trying to say because there are some English terms that they use in Japan that don’t directly translate to English. It would be a typical Japanese term for a suspension part or something, but I didn’t really know what the English equivalent of that was, so I was just making stuff up in some cases. It was hard because sometimes Japanese doesn’t translate one-to-one to English.

Sega-16: That happens a lot in Spanish as well here in Puerto Rico. My dad would be working on his car or fixing something, and he’d tell me to go to Pep Boys and get a part. He’d give me the name that everybody uses, and then I go there, and I ask the guy for the part. When he brings me the box, I’m like, “Wait, that’s what that’s called? Why would you call this that way in Spanish? It makes no sense! They just have this generic name. All cold cereal here in Spanish is “corn flakes,” even if it contains no flakes and no corn, like Rice Krispies or Fruit Loops, but it’s still called corn flakes. That’s the general term they use.

Mike Arkin: Well, there’s a whole thing about dialects in America, and there’s a website I saw once – I wish I had saved it – it was this amazing thing. It was maps of America and there were like, 20 different terms for soda. They had a map of what they called it around America. In Chicago they call it “pop,” but in New York where I’m from, they call it “soda,” but then there are some parts of the country where they just say “coke” for any kind of soda. That kind of stuff is fascinating to me. But yeah, it’s similar in Japan. They use a lot of loan words, where they have an English word for something, but that’s not the English word that I would use for that same thing. My wife is Japanese, and so we joke all the time because I’ll say, “Oh, what’s the Japanese word for this?” and a lot of times it’s just the English word pronounced differently. I’ll just laugh and go, “No, what’s the Japanese word?” She’ll say it, and I go, “Yeah, but that’s English!” It’s the same words just with the Japanese pronunciation, and there are so many of those. Sometimes it does change it a little bit, and that was the challenge with Tokyo Xtreme Racer. I’m sure I didn’t get it all right because people often think that when a game is being made there’s a team of scientists cranking it out. They don’t realize that there’s just some dude in a hoodie who’s sitting in his office thinking, “If I can get this done in an hour I can go and play some games.”

But I like I said, I love cars, and I think that on one of the boxes is a silver Mazda RX7 because that was my car at the time. The Japanese found out and got really mad. It was the box or the title screen or something, and they got really mad because they were like, “Oh, we wouldn’t do that. That’s very arrogant.” That’s not the Japanese way. It’s like, “Okay, whatever. We’re not Japanese, so it’s okay.”

Sega-16: It was your actual car?

Mike Arkin: Well, I had a silver RX7, so I said, “Make it a silver RX7.” It wasn’t a picture of my car, but they were offended by that. I was like, “Okay, whatever dudes,” but you know, Japanese game developers think a little bit differently. That franchise was great, and it was a little bit quirky. You’re trying to learn how to defeat all the bosses. There were these crazy rules. We had a chart, and it would be like, “Drive on this highway between four and six in reverse!” Some of them were crazy, but there was one guy in the office. I think he got 100%, and he had to use the chart. I wonder if that chart is on the Internet because there’s no way you could get all the bosses without looking it up.

Sega-16: I never got everything. [Laughs]

Mike Arkin: Yeah, it would be super hard if you saw the list of what you had to do to get all the bosses because I think there were like, 400 bosses or something. Some of that would just be that you had to drive for 5,000 kilometers, and it’d be like, “Okay good luck! I’ll see you on Friday!” But that was definitely that was one of my favorites.

Sega-16: I don’t know if you left Crave before they stopped supporting the Dreamcast. Did you have any projects under development when they pulled the plug?

Mike Arkin: I want to say that I think Dreamcast had wound down. I think it was PlayStation 2. We had started making games for PlayStation 2 and the first Xbox, and I think when PlayStation 2 and Xbox hit Dreamcast was dead at that point. They might have done a couple more because Crave was always doing more casual stuff. So, they might have done a couple more, but it was basically wound down at that point.

Sega-16: Were there any projects that you were working on that got shelved?

Sega-16: Were there any projects that you were working on that got shelved?

Mike Arkin: The only one that I remember is a boat racing game called H2 Overdrive, and it didn’t get shelved. It was just that the developer couldn’t finish it, and it was just a bad scene. I think that they ended up with a lawsuit. I can’t remember who sued who, but it did end up going to court because they just couldn’t deliver. They had a prototype, you know. You could drive the boat around. It was a great idea, and they just couldn’t deliver on building the rest of the game out.

Sega-16: H2 Overdrive? That’s a different game from the Hydro Thunder spiritual successor, I believe.

Mike Arkin: They used the name years later. I think it was just a coincidence it was the same name, but it was H2 Overdrive. It never came out, so the trademark was available. It was a French developer. I can’t even remember what they were called. I think they were a visual effects house that decided to make games, and they just didn’t do a very good job of it. I don’t think they ever shipped anything else. I think that was their one project. It’s hard, you know? When games are going well it’s really easy to manage, but when things start to fall apart… even as an external producer like I was back then, it’s just hard. There’s not a lot you can do. You can’t just go there and write the code for them, right? You can just say, “This is what we need you to do. Can you do it? No? Okay.”

Our thanks to Mr. Arkin for taking the time to chat with us.

Recent Comments