Even as Sega worked to get its pinball operations off the ground in Japan, it was taking steps to export its products to Europe. Starting with its electromechanical hits like Periscope (1966) and Missile (1969), Sega entered the 1970s on solid footing in the Old World. Interestingly, it didn’t do so on its own. It is important to clarify that Sega didn’t have a permanent European corporate presence until it formed Sega Europe in 1980, and the entity we’ll be discussing here began as a Sega subsidiary but soon grew to become something else.

Even as Sega worked to get its pinball operations off the ground in Japan, it was taking steps to export its products to Europe. Starting with its electromechanical hits like Periscope (1966) and Missile (1969), Sega entered the 1970s on solid footing in the Old World. Interestingly, it didn’t do so on its own. It is important to clarify that Sega didn’t have a permanent European corporate presence until it formed Sega Europe in 1980, and the entity we’ll be discussing here began as a Sega subsidiary but soon grew to become something else.

It’s a complicated tale. Sega’s presence in Spain was an integral part of that company’s emergence in the European market as a manufacturer and distributor, and the people responsible were as much a part of Sega history as anyone could be, but the connection to the company we all know didn’t last long at all. Although not part of the Sega corporate apparatus, the operation handling its arcade products in Europe had almost all the same founders – Martin Bromley, Ray LeMaire, and Richard Stewart – giving it the same coin-op DNA. If not an immediate sibling, it could most certainly be considered a cousin.

Sega Takes a Trip to Europe

While Sega began producing pinball tables in Japan, it continued to maintain and expand its electromechanical coin-op operations worldwide. At the time, U.S. manufacturers were narrowing their product lines, leaving room for Sega to introduce low-cost novelty games to fill the gap. The 1960s, however, saw the company look to exit the export business thanks to a series of setbacks, most prominent among them being the pillaging of its ideas by competitors. For some time, Sega had been battling rivals that stole its product concepts and released them as cheaper copies. The worst case came in 1970, with a premier title called Jet Rocket. The game was a more expensive title and included more sound and special effects than any of Sega’s previous offerings, but it was copied as soon as Sega showed it during location testing. According to Sega Chairman David Rosen, the main coin-op manufacturers in Chicago were racing to be the first to get their own versions into game rooms. As U.S. sales weren’t a large part of the company’s overall business, Sega concluded that devoting resources to fighting the issue wasn’t worth the effort. “Consequently, what happened is that there was an oversupply of this particular game. At that point, we decided well, we really didn’t need the export market, and for a while we stopped really exporting games for a couple years,” Rosen detailed in a 2006 interview.

The decision wouldn’t be permanent. Rosen had a bigger vision to move Sega ahead without having to pull out of any one market, and for some time, he had been considering taking the company public. He had slowly been making moves in that direction, like having Sega join the Music Operators of America (MOA), the U.S. coin-operated amusement industry’s primary trade organization. It would become the first company outside of North America to do so. Going public, however, would be more difficult. No foreign-owned company had done so since World War II, and none ever in the amusement industry in Japan. There were lots of legal barriers to overcome. Sega’s leadership considered acquiring a U.S. company into which it could merge, but Rosen’s investment bankers instead recommended that he go in another direction and find someone willing to acquire Sega. Doing so in the U.S. would be a lot easier, so he turned to the mega-conglomerate Gulf + Western, run by Austrian-born industrialist Chales Bluhdorn. Starting with a small Grand Rapids auto company in 1956, Bluhdorn had spent most of the 1960s gobbling up every company he found. It was after buying Paramount Pictures in 1967 that he made a deal to purchase Sega two years later. The buyout was finalized early in 1970 for almost $10 million and 80 percent of Sega’s stock (Lemaire retained his 20 percent). Bromley and Stewart departed, but Rosen stayed on. “As a condition of the purchase, I agreed to remain as CEO for a period of one year, although residing outside of Japan,” Rosen told the author in 2017.

“But what does this have to do with Europe?” you might ask. Well, a lot, actually. The Gulf + Western deal not only marked the start of Sega’s ascent in the U.S.; it also prompted the company to take a deeper look at the European coin-op market, where it had a solid distribution operation and had already seen coin-op success with games like Periscope. Most of all, Gulf + Western’s purchase of Sega help open the door for the factory to establish a new Spanish subsidiary that would grow to become its own company.

In the beginning, two men got Sega’s Spanish operations off the ground, Bert Siegel and Eduardo Morales Hermo. Together with interests from LaMaire and Scott Forbes Dotterer, the pair formed a new subsidiary in Parla, Spain in 1968 called Sega S.A. (also known as Segasa). “My father’s partners approached him on selling Sega to Gulf + Western,” explained Bromley’s daughter, Lauran, to the author. “At the age of 40 or so, they were ready to retire! My dad wasn’t and went on to Berlin, Spain, and England. Sega S.A. was formed to manufacture slot machines and pinball machines with an agreement from Bally for pinball.” The S.A. part of the name means Sociedad Anónima (Anonymous Society) and is a Spanish term used to identify limited companies. At first, the shareholders were anonymous and were able to receive dividends by simply presenting share certificates in physical form, which were transferable secretly. Firms did not know their shareholders in most situations, hence the name.

Getting the company started wasn’t easy. Spain was under the rule of Francisco Franco at this time and didn’t permit foreign investments that totaled more than 50 percent of the shareholding. The law prevented Segasa from technically being considered a subsidiary of Sega. Siegel and Morales Hermo used lawyers to get around this rule until it was changed, enabling ownership to revert to Bromley, Stewart, LeMaire, and Dotterer. Irving Bromberg, the other Sega co-founder and Bromley’s father, died of Parkinson’s disease in 1972, but Bromley hadn’t remained out of coin-op amusements for long since his departure from Sega two years earlier. After only about six months, he joined Stewart and jumped back in, this time in Europe to launch a chain of arcades called Family Leisure. The pair would soon rejoin their Sega comrades LeMaire and Dotterer as the major shareholders of Segasa when the law regarding imports relaxed after Franco’s death in 1975.

Spain Gets the Silver Ball

Under Franco, there wasn’t a “gaming” industry per se. Everything was classified as amusement games. For product, Segasa had to import prototypes of American or Japanese releases and patent them since it didn’t develop any of its own. “Then we manufactured or assembled them, depending on the number of components that we could produce in Spain or if we had to import from elsewhere – sometimes from Japan and sometimes from the U.S., depending on where they were available,” Morales Hermo explained in a 2022 interview with Sega-16. Between 1968 and 1973, most of the products Segasa imported were electromechanical amusement machines from Japan. In 1973, the company brought over Pong but kept up its line of electromechanical games.

That same year, Segasa began manufacturing pinball games, mostly through its 1973 agreement with Seeburg Industries, parent company of Williams Electronics. In exchange for a 50 percent stake to Seeburg, Segasa would manufacture, assemble, and distribute pinball games and amusement devices created by Williams. Additionally, it would have exclusive rights to distribute Seeburg’s coin-operated phonographs in Spain. The agreement gave Seeburg a way into Spain’s amusement market, which was difficult because of the country’s high tariffs. Segasa benefited from the expertise of Williams designers, which would soon put them in a prime position to capture much of the coin-op market.

The first Williams game brought over by Segasa was Norm Clark’s Spanish Eyes in 1974, a game released three years earlier and that featured some very 1970s artwork by John Craig (one of only two pinball machines that he did). Like the American original, the Spanish version was single player, not typical of European releases. “The Chicago plant was at capacity, and Spain used single-player games while most of the rest of the world preferred four players. To alleviate the bottleneck, Williams agreed to ship parts to Spain for assembly there,” Larry Siegel, son of the Segasa co-founder and the former Managing Director of Sega Europe, explained to the author. Segasa was Sega’s hub for the Spanish market early on, which the company initially found difficult to penetrate. Having an ally in Europe made acquiring new pinball machines much easier and cheaper for buyers. “We would manufacture them here and export them to many of these countries, especially the four-player pinball that were very popular at the time,” said Morales Hermo.

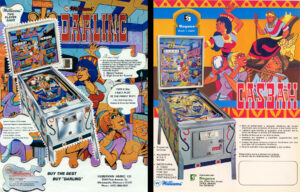

Most of the Williams pinball tables that Segasa distributed, like Jubilee (1973) and Triple Action (1974), were identical releases, but the names and number of players were changed for some. For instance, Casbah was a single-player version of Williams’ Darling (designed by Steve Kordek), and Baby Doll was a relabeled version of Norm Clarke’s Satin Doll. Segasa was soon exporting for Williams across Europe, to countries like Italy, France, and the UK out of a 70,000-square-foot facility. Spain remained its primary market, and Segasa served as the focal point of pinball exports around the continent. Between 1973 and 1975, Segasa imported multiple Williams pinball tables that sold well. Gulfstream, Spanish Eyes, Lucky Ace, Dealer’s Choice (both by Clarke), Baby Doll, and Big Ben were some of their big sellers.

Seeburg had good reason to want to enter the European amusement market. Pinball was popular there, and there were only a handful of manufacturers producing machines. They had the opportunity to put tables in over 200,000 locations in Spain alone and hundreds of thousands more across other countries like Italy and the UK. In Spain, it was possible to have thousands of machines in the field because they weren’t in just arcades; they would mostly be found in bars and pubs. These types of establishments were where most coin-op machines were placed.

A New Era Begins

1976 saw Segasa make two major changes to its business. First, as the company ramped up production, it changed its name to SONIC to avoid confusion with Sega since it was its own entity (ironically, Sega would have to buy the Spanish rights to the name years later for its Sonic the Hedgehog game). “We were ‘Sega d.b.a as Sonic’ as an agreement with Sega for quite a few years,” explained Morales Hermo. SONIC also started designing and releasing original games, the first being the electromechanical Faces in 1976. Jai Alai, released in 1978, was technically the third game to use that sport’s theme but only the second to go into production. Designer Tony Kraemer produced a prototype a year earlier but had to change it because jai alai wasn’t widely-known. His design became Disco Fever and released alongside the John Travolta film Saturday Night Fever. Since it was originally based on jai alai, it had curved, “banana” flippers mimicking the wicker cestas players used to throw the ball. Williams had already purchased a significant amount of the flippers, so they remained for Disco Fever (1979’s World Cup was the only other table to use them). Oddly enough, SONIC’s version used standard flippers.

According to Morales Hermo, the games in SONIC’S pinball line had a special touch to them, courtesy of Sam Stern, the legendary figure in the industry who had bought half of Williams from its founder, Harry Williams, in 1947 and would later start his own company, Stern Electronics in 1977. “He was the one who designed all of the production line for Sega Spain, and he even did the design of the artwork of the building,” Morales Hermo told Sega-16. Stern had sold his part of Williams to Seeburg and soon retired, but boredom soon brought him to Bally Manufacturing for a while and once more to Williams. He and his son Gary then bought the the pinball assets of Chicago Dynamic Industries, known as Chicago Coin, in 1976 and created Stern Electronics (with sizeable funding from family friend Martin Bromley). The Sterns found success with solid-state machines in 1978, like Stars, which sold over 5,000 units, and Wild Fyre, and they had a major hit in 1979 with Steve Kirk’s Meteor. Even so, Stern Electronics reduced its pinball production as the 1980s began, choosing to focus on its catalogue of popular video game titles that included Berserk and a localization of Konami’s Tutankham. It is unknown how long Sam Stern produced pinball designs for SONIC and if he did so after forming Stern Electronics. His company would produce its final commercial pinball game, Orbitor, in 1982. Two years later, Sam Stern died, and Stern Electronics would close a year later thanks to the North American arcade crash.

While pinball in the U.S. was adding new technological advancements like solid-state technology and digital displays, SONIC’s games were still behind the curve to a degree. They still didn’t have seven-segmented displays (capable of showing seven-digit scores), a feature other Spanish manufacturers had already included in their machines. They did bring over some of Williams’ newest product that included the latest innovations. For example, SONIC licensed Williams’ Flash, designed by Steve Ritchie and released in 1978 and released it in Europe as Storm. It was the first pinball table to incorporate dynamic background sound during gameplay, which increased in pitch the more time a ball was in play and adjusted according to a player’s performance. It also pioneered the use of flash lamps to give quick bursts of light during playfield objectives instead of the constant illumination of traditional lamps. Flash would sell over 19,000 units in the U.S. and be a major hit for SONIC. Around 9,400 were sold overseas, but a concrete number is not available. Morales Hermo denies that Flash was licensed for its technology, but shortly after its release, SONIC’s final two pinball releases, Third World and Night Fever (also based on the Travolta film), both had the new displays. Either way, SONIC ended the decade with a strong line of solid-state pinball tables.

SONIC continued with its own designs, bringing in people from other Spanish manufacturers such as Playmatic and Maresa. These designers didn’t have the experience of Williams’ personnel, but they were competent enough to create successful machines for the local pinball market. Many of the original designs were inspired, to say the least, from Williams tables. For example, Cannes (1976) and Monaco (1977) were just slightly altered version of Space Mission. They were so similar that SONIC didn’t even change the spelling error at the top of the playfield, which read “EXTRA BALL WHET LIT” instead of “WHEN LIT.” Original designs proved quite profitable for SONIC, and the company eventually exported 90 percent of its production to other European nations.

Throughout the 1970s, SONIC faced several difficulties with its pinball business, and one was a common scourge in coin-op around the world: counterfeiters. Spain had few laws protecting manufacturers from bootlegging, and it was incredibly frustrating to pay the hefty licensing fees and tariffs required to build and sell amusement games only to see a counterfeit version sold almost immediately. Sometimes, the copies hit the streets before the originals. “Without going any further, next week, we’re launching a new model on the market,” said SONIC Marketing Manager and former Real Madrid soccer star Manuel Velázquez Villaverde. “Well, there’s already another company offering it in its catalog. In fact, they are going to come out at the same time.” Spain lacked national legislation to battle counterfeiting, causing different areas of the country to draft their own. SONIC and its competitors faced an upward battle to combat bootleggers nationwide without a universal regulation.

As bad as counterfeiting was, it wasn’t pinball’s biggest adversary. In Europe, the legalization of gambling machines in 1978 added a new branch to SONIC’s business but did major damage to its coin-op operations because they were much more profitable. “When gambling machines were approved in Spain in 1978,” Morales Hermo explained, “the amusement machine business disappeared from bars because one gaming machine would produce $100 a day. A pinball machine would produce maybe $30 or $25, and a video machine will produce about $30. So, if you put in two gambling machines you would make four times as much money as you would with a plethora of pinball machines.” The damage had actually started even before the law was passed. When Franco died, gambling was no longer illegal. Machines started flowing in from Holland and the UK, particularly bingo games and slot machines. The 1978 legalization permitted up to three machines per bar and an unrestricted amount in arcades. Add video games into the mix, and pinball began to lose its appeal.

Perhaps the worst blow to Spanish pinball was Spain’s economic crisis at the end of the 1970s, fueled by skyrocketing inflation and labor costs, a worldwide recession, and spikes in oil prices. These issues had a brutal impact on SONIC’s pinball business, resulting in a steep decline in production. Adding to the company’s woes, the Seeburg deal ran its course around 1983, as Williams began to directly export its products to Europe. SONIC now leaned more and more on its budding video game distribution to offset the lull in pinball. By the end of the 1970s, video games had become so important that SONIC began handling games for other companies, manufacturing, assembling, and distributing their wares during this time. Japanese video game producers like Taito and Namco become customers, and Space Invaders was SONIC’s first release, followed by Namco hits like Galaxian and later Pac-Man. As video surged, pinball declined sharply. For instance, compared to the 35 machines released in Spain in 1975, SONIC shipped only two in 1981 and 1982 and none in 1983.

An Evolving Industry

Following a protracted decline, the Spanish pinball industry started to rebound in 1984, and by 1985, it had reached a production and popularity level not seen since 1975. SONIC attempted to take advantage of this revival. One such attempt was to register two Williams titles, Comet and Space Shuttle, in the official trademark office, this time with Williams’s original artwork and detailed plans. Unfortunately, rival manufacturer Cirsa-Unidesa beat SONIC to the punch, ordering 500 units of Comet, High Speed, and Space Shuttle each in late 1985 and introducing them in Spain under their own names.

SONIC forged on, and its first pinball machine of the 1980s was Gamatron, bought from Pinstar, the company formed by Gary Stern following the collapse of Stern Electronics in 1985. Although Gamatron had been produced as a conversion kit for Bally machines, SONIC’s was greatly different in design. The artwork had been completely redrawn, with a brighter and more refined appearance (the game still retained the Pinstar copyright).

SONIC was constantly looking for new tables to release, either through original designs or licensed tables. In 1985, it reached an agreement with another Spanish manufacturer called Peyper SA, founded in 1977 by legendary Spanish pinball designer and innovator Eulogio Pingarrón. He was an industry veteran, having spent 14 years designing tables for a pinball maker called PETACO (Proyectos Electromecanicos de TAnteo y COntrol). There, he had created over a dozen tables and improved several Gottlieb machines. Pingarrón’s work was so good that Gottlieb itself got word and sent a delegation to Spain to see it firsthand. He was also a familiar name to SONIC, and when Morales Hermo met with him about licensing Peyper’s Odin game, the SONIC head made a specific request. “Eduardo Morales asked that in the models provided by Peyper, it be clearly stated in a visible place that the game design was the work of Eulogio Pingarrón,” the designer revealed. For that reason, each cabinet produced of SONIC’s Odin table, called Odin De Luxe, bears the message with Pingarrón’s name on the backglass. Moreover, the back of the promotional flyer has the message, “On this occasion, SEGA S.A./SONIC has collaborated with a professional of more than 20 years in the design and manufacturing of pinball machines,” followed by Pingarrón’s signature.

As the 1980s ended, SONIC wound down its pinball production and released few tables during its later years, starting with Solar Wars, which it unveiled in March 1986. 1987 saw a collaboration with Peyper called Odisea, as well as a table based on Star Wars that was expected to be one of the year’s stronger titles due to its popular license. It was overshadowed by Pole Position (no relation to the Atari classic), another of Pingarrón’s designs. The last pinball machine SONIC produced was based on Sega’s 1985 hit, Hang-On, designed by Jose Maria Gallego Goma. It included objectives for spelling “H-A-N-G” and “O-N,” as well as loops around a wireframe track. Sadly, it didn’t include Hiroshi Kawaguchi’s classic theme song, “Theme of Love.” SONIC had debuted the Hang-On video game alongside Solar Wars, and it took advantage of the license for its final pin table. Its design was elegantly simple, and it did a decent job of channeling the video version’s cycling action.

A solid player in Spanish pinball, SONIC never made a serious attempt to enter the U.S. pinball market, likely because of the competition companies like Gottlieb, Bally, and its former partner, Williams, presented. Through the efforts of one of its founders, the company dabbled a bit in coin-op exports but never shipped anything meaningful. “I think Martin Bromley just wanted to have some fun,” Morales Hermo opined. “We perhaps exported a few other amusement machines to the U.S. because his daughter, Lauran Bromley, used to be an operator, and she became a manufacturer as well.” Also, SONIC mostly stuck to Spain with its video game distribution. It continued to bring over games by other companies, such as Nintendo’s Play Choice line, and it was not the exclusive Sega distributor of video games for Spain. Other manufacturers, such as Unidesa, brought hits like OutRun and the Mega Tech system to Europe.

Video Games Killed the Pinball Star

Over time, SONIC’s founders sold their interests in the company and moved on, or they passed away. Morales Hermo bought 35 percent of the company and became CEO in 1986, and in 1994 he bought 100 percent of the remaining interest from Sega of Japan. He attributed the changing leadership to the fact that the old guard – Bromley, Stewart, Lemaire, and Dottier – were not invested the company for its manufacturing ability, and although they were adept at that process, it wasn’t where the money was. “In manufacturing, you always run into the risk of not selling the last 50 machines or 100, and then you lose all your profits. But in operation, you win all the time,” he explained.

Morales Hermo’s decision to sell SONIC was due to a variety of reasons. First, video games had weakened pinball’s position in Spain, and gambling machines further caused the machines’ retreat from bars and pubs. SONIC itself had steadily been shifting its focus away from pinball to gambling machines entirely. Also, the introduction of the Euro in 2002 further hurt the pinball industry, and two of the largest arcade manufacturers, Cirsa and Recreativos Franco, filed for bankruptcy. Their ends came only after their harsh price competition significantly reduced SONIC’s profit margins. According to Morales Hermo, adding to these factors was a freeze in overall demand starting in January 2002 that almost completely shut down production. In April 2002, the factory filed for a suspension of payments (a deferment of debts for companies, foundations or associations that are in temporary financial difficulties) in the Madrid courts. With a favorable balance of equity, around 15 percent of Spain’s coin-op market, and net liabilities of €8.3 million, SONIC planned to pay its debt that June. However, it never recovered. Morales Hermo would remain with the company until 2004, when he liquidated and sold his assets to the Austrian gaming company Novomatic. Although not officially dissolved as of 2016, SONIC was effectively wound down in 2005.

With over 30 years in the pinball industry, Segasa/SONIC was a major player in that sector throughout Spain, and it left an impact throughout Europe. It may not have been as large as Playmatic or Maresa, two of the big four Spanish coin-op companies, but it helped establish Sega’s brand at a time when the Japanese game maker was unable to do so itself. It also showed that Sega’s name was synonymous with coin-op worldwide. Segasa/Sonic’s rise from importer and distributor to Spanish gaming powerhouse is a remarkable one, and it has, like much of Europe’s gaming history, been largely overlooked by English-focused gaming history for too long.

Segasa/Sonic bears a long and proud legacy of pinball, and many of its original games remain highly collectible today. Pinball fans should try them whenever possible, be it at a convention or other activity, to experience the European design style. Most of all, these games should be examined to see a side of the Sega brand that western fans never did.

Be sure to read part 1 (Sega of Japan) and part 3 (Sega Pinball, U.S.) of our history on Sega’s pinball games!

David Rosen image courtesy of the So I Bought A Pinball Machine blog.

Sources

- Banasik, Waldemar. “Pinballs Made in Spain.” Pinball News. February 2014.

- Bromley, Lauran. Personal Communication, May 18, 2025.

- Hernandez, Santiago. “El Fabricante de Recreativos Sega Suspende Pagos por el Euro.” El Pais, April 16, 2002.

- Horowitz, Ken. The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games. (Jefferson: McFarland, 2016).

- Morales Hermo, Eduardo. Interview by Ken Horowitz. Sega-16, October 5, 2022.

- Moreno Cuñat, Ignacio and Antionio De Santiago. “Video-Juegos: Pais Eléctrico del las Maravillas.” Micromania, October 1986.

- Rosen, David. Personal Communication, May 18, 2017.

- “Seeburg Expands International Operations.” Cash Box, September 29, 1973.

- “Sega S.A./Sonic: Desde Japón hasta Parla.” Pinball Blog, July 3, 2016.

- “Sega: Siempre a la Vanguardia.” Pin-Ball, no. 49 (June 1987).

- Siegel, Larry. Personal Communication, April 23, 2025.

- Smith, Alex. They Create Worlds: The Story of the People and Companies that Shaped the Video Game Industry, Volume I: 1971-1982, (CRC Press, 2020).

- “Solar Wars: Un Pin-Ball en la Corte del Video.” Pin-Ball, no. 40 (May 1986).

Recent Comments