Most people won’t admit it but as gamers, we’re lucky. At any time, we can pop in a favorite title, hit a button, and in a flash, a multitude of online foes await us. Be it Xbox Live or through the PlayStation 2’s network adapter, gamers are going online to play in full force. PC gamers have partaken of this particular bounty for years but it wasn’t until recently that console owners finally embraced the concept and got connected. With over a million gamers worldwide, Xbox Live has set the standard of how run an online service for its owners and one can only expect things to get even better when Microsoft’s next console rolls onto store shelves.

Of course, neither Microsoft nor Sony are pioneers in this area. There are almost as many failed attempts at bringing consoles online littering the industry’s past as there are craters on the moon. The first recorded endeavor was in 1983, with Atari’s Gameline service. Created by Bill Von Meister (founder of Gameline parent Control Video Corp), Gameline was what remained of the Home Music Store, a scrapped idea for a service that would have provided music via satellite to cable companies. Through a 1200 baud modem, Gameline was to have provided Atari VCS owners with downloadable games (for a small fee) from a central computer in Virginia. After about eight plays, the download would cease to function and the player would have to re-connect and download the game again.

Of course, neither Microsoft nor Sony are pioneers in this area. There are almost as many failed attempts at bringing consoles online littering the industry’s past as there are craters on the moon. The first recorded endeavor was in 1983, with Atari’s Gameline service. Created by Bill Von Meister (founder of Gameline parent Control Video Corp), Gameline was what remained of the Home Music Store, a scrapped idea for a service that would have provided music via satellite to cable companies. Through a 1200 baud modem, Gameline was to have provided Atari VCS owners with downloadable games (for a small fee) from a central computer in Virginia. After about eight plays, the download would cease to function and the player would have to re-connect and download the game again.

The service was supposed to have been expanded, offering later stock quotes and commodity prices, in addition to sports scores and stats. A primitive form of email and even message boards were planned, as well as banking options, airline schedules, classified ads, and horoscopes. A year’s service cost $59.99 (plus a $15 one-time membership fee) and got you the Gameline Master Module (which was inserted into the VCS’ cartridge slot), a telephone cable, a poster, a membership card, a free issue of Gameliner Magazine, and a binder with summarized rules for all games available After connecting, you needed to call and enroll, credit card in hand. Members were entitled to unlimited free downloads on their birthdays, so it was recommended that every member of the family have their own PIN number.

The modem could use both pulse and tone dialing and remembered how to connect once a connection was established. A well-designed and stable system, it was ultimately done in by the management’s inability to sign big third party publishers like Activision and Coleco. This left Gameline’s library without some of the biggest hits of the day. The following “crash” of the console industry was the final nail in its coffin. The company responsible did not fade away though. Control Video became Quantum Computer Services, a little company that later evolved into America Online.

The Gameline was eventually followed by Sega’s own Telegenesis Modem, which was touted at the Genesis’ launch but never saw the light of day in the U.S. It was released in 1990 in Japan but garnered meager support, mostly for a few text adventures and a puzzle game called Sonic Eraser. Promised titles, like Cyberball, were never made compatible.

The next try came in 1992 by a company called Baton Technologies. Sponsored in part by Atari founder Nolan Bushnell, the Ayota View, as it was called, was shown at the 1992 CES to much approval and was compatible with all the major consoles. However, Bushnell decided to curb spending by reducing the modem speed to 300 bits-per-second, which wasn’t fast enough for the twitch gaming modern titles required. After some questionable business moves, Bushnell withdrew from the project, leaving Baton out in the cold.

Not to be deterred, Baton pushed on with a prototype of its own. It was also compatible with the three current game systems of the time and ran at an impressive 2400 bits-per-second, which was enough for any and all one-on-one gaming to be had. Moreover, it was cross-compatible. BattleStorm, a tank combat simulation, could be played on the NES against gamers on the Genesis. This was incredibly innovative and has never been attempted since. Two other games, Terran Wars and Sea of Vengeance (a 2-player naval combat game), both also for the NES, were planned. Unfortunately, Baton failed to attain licensing for their modem from any of the major companies and after AT&T stole authorization right out from under them, the company closed its doors and the Baton Teleplay Modem faded into history.

All of these may have technically been the first tries at bringing console gaming online but they weren’t full-fledged services. For that reason, Sega must be mentioned. They first entered the arena with their Netlink modem, which was available for the Saturn console and sold for $199 ($400 packaged with the Saturn itself). Using a 28.8 kbit/s modem, the Netlink allowed gamers to use their own ISP (if it fit the technical specifications of the unit). A handful of titles were playable, among them Virtua On and Sega Rally, but the Netlink failed to catch on, probably due to the Saturn’s miserable attachment rate in the U.S. and it’s own high price. The project died quickly, followed soon thereafter by the Saturn itself.

Sega, however, wasn’t done with online gaming. With their next console, the Dreamcast, they went all out. SegaNet was the first true attempt at a true gaming service. Setting the stage for Xbox Live in terms of options and viability, Sega’s online program was slow to start but actually achieved a pretty good level of quality before the system was prematurely put down in March of 2001. Some 250,000 gamers enjoyed Phantasy Star Online and while few other titles reached that level of success, it was enough to show companies that money could be made by making their titles modem-friendly. Before Sega’s failed attempts with the Saturn’s Netlink and Dreamcast’s SegaNet, modems were only used in gaming for simple things, like downloading games for a fee on the Intellivision or doing simple banking on the Famicom via Nintendo’s Tsushin System. Atari had also thought about offering a modem with their 2600 system (the “Graduate” 2600 Computer) but canned the idea when the console market lost its steam and the company’s fortunes took a turn for the worse.

Sega, however, wasn’t done with online gaming. With their next console, the Dreamcast, they went all out. SegaNet was the first true attempt at a true gaming service. Setting the stage for Xbox Live in terms of options and viability, Sega’s online program was slow to start but actually achieved a pretty good level of quality before the system was prematurely put down in March of 2001. Some 250,000 gamers enjoyed Phantasy Star Online and while few other titles reached that level of success, it was enough to show companies that money could be made by making their titles modem-friendly. Before Sega’s failed attempts with the Saturn’s Netlink and Dreamcast’s SegaNet, modems were only used in gaming for simple things, like downloading games for a fee on the Intellivision or doing simple banking on the Famicom via Nintendo’s Tsushin System. Atari had also thought about offering a modem with their 2600 system (the “Graduate” 2600 Computer) but canned the idea when the console market lost its steam and the company’s fortunes took a turn for the worse.

Over the next couple of years, many companies offered services where you could download games to your system, such as the Sega Channel and Nintendo’s own Satellaview. You could not play against anyone, however. While all these tries at incorporating a modem are well and good, they aren’t enough of a push forward to really be considered the first big step in the evolution of online console gaming. For that, we need to look before Sony, Microsoft, or Sega had even considered making online play a staple of their business plan. Back in 1995, no one thought that consoles could ever be successful online and only one company was willing to take a chance on going ahead with an actual service. Before Live, even before Netlink on Saturn, Catapult’s Xband was the first real attempt to integrate an online service into the console realm beyond simple downloads. The first service to actually get beyond the planning stages, it achieved only lukewarm success and disappeared from the market place in less than two years but the effect of its passing is still being felt. Gamers were finally able to enjoy what PC gamers had available to them: the ability to challenge an opponent long distance. Yes, the Xband left quite a mark on the industry, one that Sega would later revive and Microsoft would virtually perfect.

How It Worked

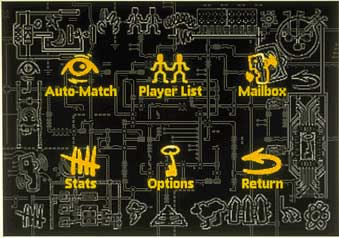

Going online in November of 1994, Catapult’s Xband was at first only available for the Sega Genesis. The system was very basic in concept and required nothing more than a Genesis and standard telephone line for play. The Xband unit itself retailed for an amazingly low $19.95, which made it very attractive for gamers looking for new gadgets for their console. No game modification was needed, since the unit came equipped with a “smart chip” that essentially modified execution of the game’s program to make it playable online. You simply placed the unit into your system with a game inserted (similar to Galoob’s Game Genie), plugged your phone line into the back of the Xband unit, and powered up. Once connected, you arrived at the home page, which gave you several options. If you wanted to jump right into the action, you could use the “auto match” feature to find someone online instantly. This instructed Catapult’s server to find an opponent of the same skill level as you anywhere in the U.S. who wanted to play the same game at the same time Mortal Kombat and NBA Jam were quite popular). The server then directed one of the two modems to call the other. $4.95 got you fifty connections (the amount of times the network connected you to an opponent) a month, while $9.95 gave you unlimited local connections, with the first month of play free. For $3.95 an hour, you could play long distance anywhere in the continental United States. Perhaps this wasn’t the most practical setup, as more than a couple of hours of play would have been too expensive. However, if you had a decent local scene, you could conceivably spend an endless amount of time playing head-to-head matches with more opponents than you’d ever need. I have heard rumors that some games were playable in 2-on-2 matches but this has not been confirmed.

An interesting footnote is that the service gave you an icon and game name to maintain privacy. This is basically the same as Xbox Live’s “gamertag.”

The Xband wasn’t only for simple one-on-one matches though. There was actually something of a service to go along with the match connecting. The modem included a ROM-based operating system, which offered a simplified interface and even email (called “Xmail”)! Moreover, every time you connected, two online newspapers (called “bandwidth”) with the latest info were downloaded for you to read. The server also kept track of stats, ranked players, offered game tips and firmware upgrades, and informed users of competitions and updates on other players. After matches, you could “chat” with your opponent, using an interface similar to that used for the email. Amazingly enough, Xband even had a call-waiting feature!

The Xband wasn’t only for simple one-on-one matches though. There was actually something of a service to go along with the match connecting. The modem included a ROM-based operating system, which offered a simplified interface and even email (called “Xmail”)! Moreover, every time you connected, two online newspapers (called “bandwidth”) with the latest info were downloaded for you to read. The server also kept track of stats, ranked players, offered game tips and firmware upgrades, and informed users of competitions and updates on other players. After matches, you could “chat” with your opponent, using an interface similar to that used for the email. Amazingly enough, Xband even had a call-waiting feature!

To control kids from spending half a day playing someone clear across the country and thereby leaving their parents in bankruptcy, Catapult implemented a parental control feature which automatically made the unit only call locally unless specified otherwise. Parents could also control just how long their kids would play on the network. These controls could be updated at any time.

For such an early attempt at online gaming, the system was surprisingly stable. According to Catapult:

XBAND communication latency is low enough (<50 milliseconds) that the response delay in even a coast-to-coast video game is barely perceptible by an expert human game player (New York to Los Angeles latency is about 35 milliseconds through copper or fiber optics). For comparison, Internet latency ranges from 200 milliseconds to more than one second, so Internet games such as NetTrek need to allow for arbitrary delays. Online services connect through x.25 packet-data networks that have latencies between 250 milli-seconds and 1.5 seconds.

Droppers Are Not a New Thing

Remember how mad you got when those Blanka-abusing cretins abruptly ended the game when they were losing in Capcom vs. SNK 2 for Xbox? Well, they weren’t the first. This was a common problem for the Xband service as well. Even when in beta testing, the bottom-feeding scum known as “droppers” reared their ugly heads. At first, sore losers would simply hit the reset button on their consoles to save themselves from gaining a loss to their stats. This would make the game freeze, causing the system to realize the connection had been lost and then restart. When the dropper and his opponent reconnected, the service would offer its best guess as to what went wrong.

Those who hit reset were very comfy at the beginning of the service. The network essentially downloaded a patch to the unit to make each game playable online and early ones were sometimes unstable. This caused games to occasionally lock up, making it necessary to reset the system. Though later patches were more stable and attempts were made to identify abuse, it was impossible to catch every dropper. Most games, however, were successful in avoiding this abuse by automatically penalizing the dropper with a loss and giving a win to their opponent. This depended on the last scores sent to the server by the unit before the connection was cut.

Droppers were quite sneaky, using one of three despicable methods to save their precious stats. They could simply call themselves (if you had call waiting), hit reset, or simply disconnect the phone cord from the unit itself. Unfortunately for those with call waiting, the service detected this and either restarted the game completely over or from the beginning of the last period played (e.g. the end of the previous quarter in Madden or NBA JAM). Some droppers called themselves over and over, causing their opponent to either be outscored or to just quit in frustration. If they were behind when they quit, they would get the loss and would receive nothing if they were winning.

Once the option to reset Genesis was no longer available, droppers tried their last option: disconnect the phone cord. Once they reconnected, the reset detector sent them an email detailing what happened and how it affected their stats. This lead to a deluge of customer service calls offering all kinds of excuses as to why the cord had been disconnected. “My little brother tripped on the line” and “the lights went out” were common pleas. Not even attempts to monitor power levels on the telephone line were effective in combating this, however, so opponents were awarded wins to keep them happy while droppers were not penalized in order to keep them from complaining. This hurt the service in the long run by scaring off potentially honest gamers, much the same way current droppers have scared off many players from games like Capcom vs. SNK 2 on Xbox Live.

Catapult Slings the Xband to Retailers

Even with the problem of droppers, the service was initially a smash success in its five-city test run (San Francisco, Dallas, Atlanta, New York, and Los Angeles). Catapult intended to capitalize on this momentum and announced on August 10, 1995 that it was teaming up with Blockbuster Video to expand their Xband sell-through program. It was one of the most successful national rollouts in Blockbuster history, increasing the number of retailers selling Xbands to 4500. Blockbuster employees were trained in the use of the service and its features, while four feet of display space with headers and four shelves of space were allotted for the product. Not to shabby for a concept most people considered to be unfeasible on consoles. Additionally, Catapult created a two-minute video about the service that could be rented from Blockbuster for free. By 1995, Xband also supported the SNES, offering gamers on both consoles such hits as Killer Instinct, Madden ’95, Weapon Lord, NBA Jam, Super Mario Kart, and Super Street Fighter II. At its height, the service boasted that gamers spent 20 hours a month online, playing about a million games and sending or receiving around 80 messages.

Even with the problem of droppers, the service was initially a smash success in its five-city test run (San Francisco, Dallas, Atlanta, New York, and Los Angeles). Catapult intended to capitalize on this momentum and announced on August 10, 1995 that it was teaming up with Blockbuster Video to expand their Xband sell-through program. It was one of the most successful national rollouts in Blockbuster history, increasing the number of retailers selling Xbands to 4500. Blockbuster employees were trained in the use of the service and its features, while four feet of display space with headers and four shelves of space were allotted for the product. Not to shabby for a concept most people considered to be unfeasible on consoles. Additionally, Catapult created a two-minute video about the service that could be rented from Blockbuster for free. By 1995, Xband also supported the SNES, offering gamers on both consoles such hits as Killer Instinct, Madden ’95, Weapon Lord, NBA Jam, Super Mario Kart, and Super Street Fighter II. At its height, the service boasted that gamers spent 20 hours a month online, playing about a million games and sending or receiving around 80 messages.

The service was subsequently expanded to PCs, using the RAPID (Reduced-latency And Predictable Internet Delivery) system, which combined both a proprietary IP service and an ATM backbone to route gamers. On July 16,1996 Catapult announced a partnership with game publisher Accolade to bring Star Control 3 online through the Xband system. The game CD included software to connect to the network and allowed gamers to play against each other in Hyper Melee, a space combat feature. This was part of Accolade’s attempt to include online play with its games on the PC.

1996 also saw the Xband support the Sega Saturn. It used a 14400 bps modem and allowed for several titles, such as Virtua Fighter, Sega Rally, Daytona USA, and World Series Baseball to be played in one-on-one matches using a media card that was inserted into the modem. An optional keyboard was also made available. The system was released in Japan as well as America but floundered.

With all the marketing muscle Catapult threw behind its service, you’d think that the Xband would have remained a runaway success that thrived. Sadly, this was not the case.

From Xciting to Xtinct

Reaching its peak in mid 1995, the service saw its user base begin to taper off by the middle of the next year. Catapult eventually discontinued the Xband and the servers were shut down on April 30, 1997. A lack of new interest in the service, as well as the demise of 16-bit systems were cited as the reasons behind the Xband’s failure. It is most likely though, that what ended its run is ironically the very thing it tried to bring to gamers in the first place: the internet. Online PC gaming exploded in the late ’90s, offering gamers many more options of play and a multitude of titles not even remotely possible on the Xband. Even with the power offered by the next generation of consoles, it was simply not enough. Sega would learn this very lesson when its Netlink service crashed and burned in 1998. Catapult eventually merged with MPath and quietly disappeared from the gaming scene, thus ending the first great chapter in console online gaming.

Even with its failure, one cannot simply discount the Xband’s contribution to online console gaming. It was the first to seriously attempt such a feat and laid the groundwork for SegaNet and ultimately Xbox Live. It was darn cool at the time and even if it looked a little awkward on our Genesis console, what it offered was something that had never been offered before; something that today, we take for granted.

Sources

- “Accolade’s Star Control 3 Comes to Xband PC.” Coming Soon Magazine, 1996.

- Catapult Press Release. “Xband on PC.” Gamezero.com, February 27, 1996.

- Cifaldi, Frank. “Spotlight: Baton Teleplay Modem.” Lost Levels Online, October 6, 2003.

- McFadden, Anthony. “Handling Unsportsmanlike Conduct Online”. Fadden.com, 2002.

- Info. “Saturn Xband” Sega of Japan.

- Info. “Teleplay Modem – Baton Technology. The Warp Zone.

- Info. “Consoles Online: How Many Attempts Were There?” TNL Forums, November, 12, 2004.

- Info. “Xband Modem & Network.” Gamersgraveyard.com.

- Info. “Xband Press Announcement.” Gamezero.com, August 10. 2005.

- Info. “Xband Video Game Network.” Siggraph.org., 1995.

- Skelton, Dan. “Remembering the Gameline.” 2600 Connection.

Recent Comments