Historically, it seems that video games have something of a bad reputation in society. Simply look at all the instances in which the industry has been tied to violence among youths (without any solid research to sustain the contention), and it’s apparent that video games make a convenient scapegoat. Gamers, particularly Sega fans, remember the 1993 U.S. Senate hearings on video game violence, and just recently, President Trump has linked game violence to school shootings in places like Parkland, Florida. The practice of associating games with negative influences is not new. Virtually since its conception, video gaming has been on the receiving end of controversy. Any time there is a social or moral issue concerning young people, heads often turn, and fingers rise to point at video games as corrupters of children and the destroyers of healthy families.

Historically, it seems that video games have something of a bad reputation in society. Simply look at all the instances in which the industry has been tied to violence among youths (without any solid research to sustain the contention), and it’s apparent that video games make a convenient scapegoat. Gamers, particularly Sega fans, remember the 1993 U.S. Senate hearings on video game violence, and just recently, President Trump has linked game violence to school shootings in places like Parkland, Florida. The practice of associating games with negative influences is not new. Virtually since its conception, video gaming has been on the receiving end of controversy. Any time there is a social or moral issue concerning young people, heads often turn, and fingers rise to point at video games as corrupters of children and the destroyers of healthy families.

The gaming industry has spent its entire life combating this negative perception. The fight began in arcades, in the late ‘70s and ‘80s when towns and cities passed ordinances and laws to keep children out of game rooms. Arcades were perceived as evil dens of misconduct, and it was society’s moral obligation to protect its youth from gaming’s dark influence. Arcades fought back, countering government legal action in court while cleaning up game locations. Two of the major chains, Time-Out and Sega’s own centers, poured millions of dollars into renovations that included bright paint, signs with clearly-stated rules, and even acoustically-treated paint to muffle noise. Uniformed attendants patrolled the arcade floor, providing constant maintenance to the machines and keeping the area clean and family-friendly.

The AAMA & Sega vs. Underage Drinking

The controversy had died down somewhat by the middle of the 1980s, but the arcade industry maintained its efforts to project a positive image. The American Amusement Machine Association (AAMA), the trade organization that represented arcade manufacturers, parts suppliers, and distributors, had been formed in 1981 to promote and protect the industry, and that mandate included social issues. One of the biggest topics of the decade was drunk driving, particularly among teenagers. There was a massive campaign against the problem, led primarily by the non-profit organization Mothers Against Drunk Driving (M.A.D.D.), which was formed in 1980 by Candace Lightner after her 13-year-old daughter was killed by a drunk driver. The organization grew rapidly in both size and popularity, achieving major success with the passage of the National Minimum Drinking Age Act in 1985. By 1987, M.A.D.D. was nationwide and was having a major effect on the national consciousness regarding underage drinking.

The AAMA, still very much thinking about the long fight to legitimize arcades in the public eye, saw a chance to create positive news (for once) about video games and youth by attaching itself to the national anti-drunk driving movement. By uniting with M.A.D.D., the game industry could do a public service while also adding to the good will it had been trying to generate for the past few years. “The association’s goal,” explained AAMA’s Executive Director David Weaver, “is to portray the coin-operated amusement industry in a favorable light while striking a blow against drunk driving by teenagers.”

Bally/Midway National Sales Manager Mark Whittaker conceived of a plan where the AAMA would create an anti-drunk driving public service announcement (PSA) with arcades as its settings. He pitched the concept and script for a 30-second spot that would be distributed nationally to local stations that were members of the National Association of Broadcasters. Weaver oversaw the project, involving several AAMA members in the gaming industry, including Sega. The coin-op giant’s role in the affair was a small but important one to increase teen awareness of the dangers of drunk driving.

Bally/Midway National Sales Manager Mark Whittaker conceived of a plan where the AAMA would create an anti-drunk driving public service announcement (PSA) with arcades as its settings. He pitched the concept and script for a 30-second spot that would be distributed nationally to local stations that were members of the National Association of Broadcasters. Weaver oversaw the project, involving several AAMA members in the gaming industry, including Sega. The coin-op giant’s role in the affair was a small but important one to increase teen awareness of the dangers of drunk driving.

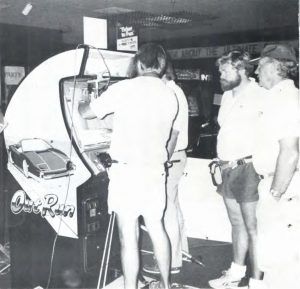

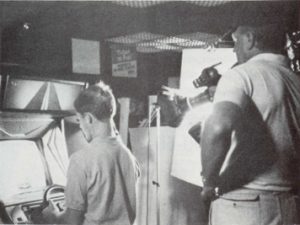

In the ad, a young teenager walked into an arcade and looked over all the games available. He decided to play Sega’s OutRun. As he played, the camera panned in over his shoulder to focus on the game screen while the narrator explained that video games were one thing, and real life was something else. Titled “Life is Not a Game,” the ad was shot over the course of an entire day at the Bally’s Aladdin’s Castle in the Spotsylvania Mall in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Von Spaeth Productions, an independent studio that made documentary films for the National Park Service and other entities, was hired to film the PSA, and a young man named Billy Hamilton was cast as the game-playing teen. After completion, the ad was shown to the AAMA board of directors in Chicago in early September 1987, who greenlit its release, and broadcasts started at the beginning of 1988.

Weaver was very pleased with Sega’s decision to allow OutRun to be used without demanding credit for its appearance. Sega didn’t even require the game to be identified. “Sega was highly interested in the greater goal of working against drunk driving and portraying this industry in a favorable way,” Weaver told RePlay magazine.

The AAMA/M.A.D.D. collaboration yielded national results. In April 1989, the FBI announced that it would be incorporating the ad into its own anti-drunk driving campaign, the same campaign that included the now-famous “Winners Don’t Use Drugs” message before game attract modes. The PSA was already receiving heavy play time nationally, but its addition to the FBI program added an estimated 500,000 additional viewers. AAMA Executive Vice-President Robert Fay stressed the importance of bringing the announcement to as many teens as possible. “We want America’s youths to know that life isn’t a game and that sometimes, the price you have to pay for your actions in real life is just too high.”

Both the AAMA and M.A.D.D. continued to work with the National Association of Broadcasters, organizing a National Youth Conference in March 1989 in Washington D.C. The activity was a preamble to “Operation Prom/Graduation,” a campaign focused on bringing attention to the underage drinking and driving issue. Around 300 youths and adults attended, and Sega provided three coin-ops from its Time-Out Amusements center in Fredericksburg, including OutRun. The company also gave away OutRun t-shirts to the lucky participants. An abridged version of the AAMA OutRun ad would air on MTV at this time, continuing the effort to expand the public consciousness about the dangers of the issue.

Gaming for the Greater Good

Sega’s role in the AAMA’s campaign may not have been center stage, but it was an important step for the game-maker. By inserting itself into the discussion, it not only garnered some good will from the public, it showed that it was an industry leader. Sega had always been willing to take on difficult and uncertain roles, but most of those instances came before its departure from U.S. manufacturing in 1984. Its new U.S. outfit, Sega Enterprises USA, had only been established a few years earlier, and it was looking to increase its standing in North America.

Sega’s role in the AAMA’s campaign may not have been center stage, but it was an important step for the game-maker. By inserting itself into the discussion, it not only garnered some good will from the public, it showed that it was an industry leader. Sega had always been willing to take on difficult and uncertain roles, but most of those instances came before its departure from U.S. manufacturing in 1984. Its new U.S. outfit, Sega Enterprises USA, had only been established a few years earlier, and it was looking to increase its standing in North America.

The video game industry may have not shaken free of its negative image in some circles, but it’s apparent that companies like Sega have tried to show that the gaming can do good. Sega would find itself at the forefront of such battles, in both the arcades and with its home consoles, often leading the charge, such as with its rating system. The arcade legend was instrumental in bringing video games out of that dark age when towns were passing ordinances to keep arcades out, and efforts such as the collaboration with M.A.D.D. were among the reasons why.

Image 1: The film crew gathers around Sega’s OutRun video upright, the “star” of AAMA’s TV public service announcement for Mothers Against Drunk Driving.

Image 2: AAMA ‘s Dave Weaver. Mark Whittaker of Bally’s Aladdin’s Castle, and Nick Von Spaeth of Von Spaeth Productions take a break outside the Fredericks burg. Va location during filming.

Image 3: A scene from AAMA’s 30-second public service announcement.

Images/captions 1 & 2 property of RePlay magazine. Image/caption 3 property of Play Meter magazine.

Sources

- “AMAA & FBI Deliver Anti-Drinking Message.” Cash Box. 29 April 1989, pp. 29.

- “AAMA Board Endorses ‘AAMA-Protect’ Plan.” Cash Box. 3 Oct. 1987, pp. 37.

- “AAMA Joins Forces with MADD.” Play Meter. May 1989, pp. 21.

- “About AAMA.” American Amusement Machine Association. 2018. Web. 28 Mar. 2018.

- Kunen, James. “Drunk Driver Larry Mahoney Gets 16 Years for the Kentucky Bus Crash That Claimed 27 Lives.” People. 8 Jan. 1990. Web. 28 Mar. 2018.

- “News Feature: Public Service Spots.” Play Meter. Nov. 1987, pp. 68, 70.

- “Thinking Big.” RePlay. Oct. 1987, pp. 32, 36.

Recent Comments