Capcom’s release of Street Fighter II for the SNES in 1992 was a watershed moment in gaming history, one in which Genesis owners were initially left watching from the sidelines. Eventually, They got the excellent Special Champion Edition and all was right in the fighting game world.

Capcom’s release of Street Fighter II for the SNES in 1992 was a watershed moment in gaming history, one in which Genesis owners were initially left watching from the sidelines. Eventually, They got the excellent Special Champion Edition and all was right in the fighting game world.

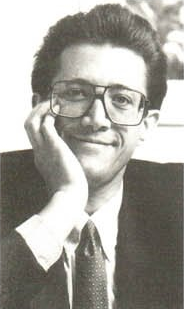

Someone who saw those events transpire from the Sega and Capcom perspective was Joe Gillin, who served as the Director of Marketing for both companies during the height of the Genesis’ popularity. At Capcom, he helped launch the SNES version of Street Fighter II before moving over to Sega, where he was involved in the Sega Club and Sega Sports brands.

Sega-16 recently had the opportunity to talk with Mr. Gillin about his career at two of gaming’s most storied publishing houses.

Sega-16: Let’s start at the beginning of your career in video games. You started at Capcom, correct?

John Gillin: That is correct, yes.

Sega-16: And you came over from Del Monte?

John Gillin: Right. I had started my career in classic consumer packaged goods marketing, but I made the move to Capcom. Joe Morici, who you have spoken to in the past, was looking for somebody who had some classic marketing training, especially for packaged goods. Video games at that time being packaged goods that were sold off the shelf just like a can of beans. He was looking for somebody to bring that discipline into Capcom, so he hired me.

Sega-16: Did you find it to be like a radical change of environment, or was it more or less the same style that you were used to?

John Gillin: It was very different. Del Monte was part of a very large company at the time. They had been owned by Nabisco Foods, and a few years before I joined Del Monte, Nabisco Foods was acquired by RJ Reynolds, the massive tobacco conglomerate, creating the company RJR Nabisco. The cigarette company had bought Nabisco foods in order to diversify what they were selling because they saw that tobacco was in the crosshairs of the government and consumer rights groups. The acquisition was designed to help add some diversity to their portfolio and stabilize their stock and also to hopefully hold people back and say, “Hey, we’re not just a tobacco company,” but they had also bought Del Monte as part of that package. So, you had a massive Fortune 500 company. You’ve got layers of people, which equates to bureaucracy a lot of the time. You’ve got a lot of corporate structure.

Del Monte at the time was a company that was 100 years old, so it was a very kind of a staid company. So, to go from there into Capcom, which was a fairly small company, as far as its U.S. footprint was, and then having a fairly small headquarters back in Osaka, it was thrilling. It was exciting. It was in the entertainment field. And absolutely, I was thrilled.

Sega-16: I saw that you were involved in the release of Street Fighter II on the Super NES.

John Gillin: Yes. I joined Capcom in the summer of 1992 and was told by Joe that they had an upcoming video game release that they were hoping was going to be pretty big, and that was Street Fighter II. I had spent some time in arcades – I was certainly not an arcade rat – but I knew enough about video games, having played them, that I had an appreciation for Street Fighter II. And the fact that it was going to be ported over from coin-op to the Super NES system was a huge deal. And we were looking at a ship date in August. Joe had done a little bit of marketing prior to that, but I then got on board and we really put a lot of other marketing programs in place in order to help support the launch of it. And it was an exciting time.

Sega-16: That must have been a pretty high-pressure release. As a gamer back at that time, I can tell you that there was immense anticipation for that game. I mean, everybody was going to buy that game. So, I can imagine what it must have been like. Although, thinking about it, that game was just a tsunami of popularity on its own. I know that you marketed it, but that’s the kind of game that you really don’t seem to have to do much to push. I mean, anyone that I knew, you didn’t have to sell them Street Fighter II.

John Gillin: Exactly. You know, this was long before the Internet, so word of mouth was a very, very different animal at that point in time. A lot of it was hanging out at the arcades; a lot of it was going over to your friend’s house; a lot of it was talking about it in school. And of course, our target was the 13, well, probably 11 to 17-year-old demographic. That was who we were really going after at that time.

And at the time, if you’ll recall, the Super NES had only been on the market for, at most, maybe six months – I forgot the exact launch date – but they had launched and they had a very, very limited number of titles that were available for the machine, and most of those were all internally developed Nintendo games. So, the third parties were all trying to develop for the platform. There had been a few hits, I don’t recall what they were on Super NES, but Street Fighter II was really being anticipated as a hardware driver to really, really amp up the hardware sales that Nintendo desperately needed because they were getting their clock cleaned in the U.S., at least, by the aggressive marketing of Sega and the Genesis, and their really irreverent Sega scream commercials, which really, adults were going, “What in the world is this?” The kids are like, “Yeah! Sega!” It was just anti-authoritarian, and so Nintendo was really looking for Street Fighter II to help get the installed base, to help lock up TVs with their Super NES system. There was marketing that was going to be done. A lot of it was just to help feed the excitement, but also there were some people that weren’t as tied in, and we would do things to just try to hype it, let people know when street date was, things like that.

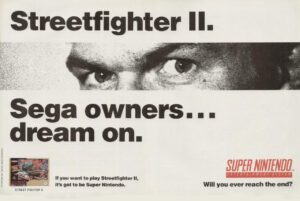

Sega-16: And that leads directly into my next question. There was a British ad for the game, for Street Fighter II, that it said, “Street Fighter II, Sega owners dream on. If you want to play Street Fighter II, it’s got to be on Super Nintendo.”

John Gillin: Right. And I don’t recall specifically doing that, but it’s been a while. But Nintendo was very excited about using Street Fighter II as a bludgeon against Sega. And so there was a fair amount of swagger and bragging out of Nintendo to really kind of say, “We’re back. We’re in this game again, and we’re going to take over this category once we have our hardware placed in so many homes.” And Street Fighter II was viewed as a great vehicle to help get it there.

Sega-16: I think it was like a year later that Capcom released the Genesis version, the Special Champion Edition.

Sega-16: I think it was like a year later that Capcom released the Genesis version, the Special Champion Edition.

John Gillin: Yes, exactly.

Sega-16: Sega had always gone for the older market. Instead of the kid who played Nintendo, they would go for his older brother. So, I wanted to ask you if there was any difference with how Capcom marketed its games on the Genesis versus on the Super NES?

John Gillin: That’s a great question, we had a lot of consumer magazines that we would routinely run advertising in. At that time it was GamePro and EGM [Electronic Gaming Monthly] who were the two big players in that field. And so, we did a fair amount of print ads, and we did some TV ads. We didn’t do TV ads for the Special Championship Edition, but we did do some TV ads to support the initial Street Fighter II launch on the Super NES. It was always fun doing the TV, obviously.

By the time we got to a year after the initial Super NES launch of Street Fighter II, I came up with an idea which was very expensive, but again, it was all about feeding that word of mouth. I went to Joe Morici and said, “What if we were to direct mail 100,000 VHS tapes to kids?” which meant we could employ a couple of different strategies there. One was to notify and hype the launch of the upcoming game. Then, we could put some tips and tricks in there as well, since again, pre-Internet, kids had to go to print mediums in order to find tips and tricks. And we thought, “Well, if we were to bury a few into this promotional videotape, then kids who receive it will feel like they’ve got a little bit more of an inside track than other kids, and they can also share it. That would just help feed the word of mouth promotion that we were looking to start.” And it ended up being tremendously successful. We used that on a couple of other releases. Aladdin was another video game that we used direct-to-consumer VHS promotions. It was a really, really good strategy to help hype the titles. I really enjoyed coordinating those direct mail programs – sitting down, doing scripts, and shooting video with some very, very talented people.

Sega-16: Do you recall how well the Genesis version of the game sold? Was Capcom satisfied with the results?

John Gillin: I don’t recall what the numbers were. I do remember that by the time we got Special Championship Edition out… by that point in time, Mortal Kombat had moved into the marketplace. That was the new thing that was attracting a lot of attention, a lot of excitement for kids. So, I don’t recall the numbers. I don’t think that Special Championship Edition actually exceeded the Super NES version because Super NES at the time, of course, had first-to-market advantage and they were unique and notable. And the great thing is that we backed into a marketing strategy, which we didn’t realize – if you’re familiar with the concept of scarcity marketing, where you create more excitement for a product by not allowing every single person to get it who wants it. We had a street date in, I believe it was mid- to late August. And Joe Morici could speak to the numbers better than me, but I think we were sitting there, blowing the doors off the barn, and taking an incredibly risky inventory position by ordering so much; it was probably 300,000 units of Street Fighter II. Remember, this was back in 1992, when the debacle of the E.T. game on Atari was still fresh in the minds of a lot of people. The last thing you would ever want to do would be to over-order and then have to bury hundreds of thousands of cartridges in a landfill somewhere. That’s the stuff that kills companies.

The good news was that we had a great track record. We knew there was a lot of pent-up demand just based on what we were hearing, and what we knew about the arcade side of the business. So, it wasn’t like we were putting some brand new game out there. This one actually had some heritage and some intellectual property awareness within the community. But we ordered a lot of cartridges and those sold out within a few days. And it was all of a sudden, “Oh my God! We didn’t expect it to go that fast!” So, we went back to Nintendo and said, “Hey, we need another order.” And Nintendo being Nintendo – very ordered, very structured, an old school company – they said, “Okay, well we’ll get those to you in 90 days,” which at that time was the turnaround time between placing an order of cartridges and getting them into stores. And we said, “We don’t have 90 days to wait.” And they said, “No, you’re in line and that’s how long it’s going to take” because they had limited manufacturing and they were manufacturing cartridges for themselves and other parties. We kept pressing and pressing. We went all the way up. We had the owner of Capcom calling the owner of Nintendo. It really put pressure on them and it went back and forth. Finally, they decided to leapfrog our order over a number of other orders. Those new cartridges came in probably, I think, in October, and those quickly sold out again. So, we’d go in for a third order, and this whole time, kids are just panicked. They can’t get their hands on Street Fighter. They really want it so they can go home and practice so that when they go to their friend’s house, they can kick their friend’s ass. Yeah, it was just crazy. And so the demand kept building as kids couldn’t get their hands on it. I think we were able to sneak in one last shipment before Christmas that year.

We blew the million unit mark out of the water that year. And that was something that had never been done before in the video game industry. So, at the time it was really a massive, massive accomplishment, an achievement. It was a fun time. At the same time though, you’re sitting there saying to yourself, “God, if we can’t get the game into these kids’ hands, are they just not going to buy it later?” No, they were going to buy it and more. So, it was great. It really worked out well.

Sega-16: Everyone I knew had that game. And the Super Nintendo. And I had friends who had both the Super Nintendo and the Genesis. And they had the Super Nintendo version. And then they bought the Special Champion Edition. And I even had a friend who – there was an offer that Capcom had that you could get a controller – and they had the controller as well. And it was a game that you just, you had it. Everyone had it. It was mandatory that it had to be in your game library.

John Gillin: It was so much fun. And for me, I have to defer to so many other people at Capcom because I arrived really late to the party. I’m thrilled to have been a part of the last few yards of bringing the football in for a touchdown, and we came out with a number of iterations thereafter. It was Special Champion Edition, it was Turbo. It was a really great time. Actually, I look back at my career and that period when I was at Capcom and Sega is far and away the greatest time of my entire career, just absolutely phenomenal. A couple months ago, Sega had a reunion in Redwood City and there were 120 Sega alumni there, and it was so much fun to go and see people I hadn’t seen in 30 years. We just had a fantastic time. I think most Sega alumni, to a person, would all say that that time that we all had when we were at Sega was the greatest time of our careers. We were all so fortunate to have caught lightening in a bottle during that period.

Sega-16: I hear that a lot in interviews. A lot of people say that.

John Gillin: Yeah, it was a great time.

Sega-16: I know Capcom came on board with Sega in late 1992 and they were releasing games, but do you recall if there were any plans to market games or were there any discussions of releasing games on the Sega CD?

John Gillin: Sega CD, no. As far as the dynamics between Capcom and Sega, I’m going to talk in generalities. I can’t get into specifics because I just don’t know, but my understanding at the time was that the owner of Capcom had family relationships, I mean this goes back generations, but family relationships with the folks that owned and ran Nintendo. There was a very, very strong loyalty between the two companies and Capcom was going to forever be a Nintendo licensee. It wasn’t until there was this massive success of Street Fighter II that Capcom really ended up having to go to Sega in order to try to optimize its business opportunities. But Capcom was always going to be deferential to Nintendo. If you go back and you look, at least back then – it’s different now – but if you look back then, Capcom really didn’t come out with many Sega games at all just because its primary loyalties were to Nintendo, and Nintendo valued Capcom a lot as well for its dedication and loyalty. So, there was a really good relationship there. I don’t know whether Capcom went to Nintendo and said, “Would you mind if we released this on Sega just so we can optimize our business fortunes?” I don’t know whether there was ever any permission put out by Nintendo, but I would not be surprised if there were discussions between Capcom and Nintendo about the opportunity to release Street Fighter II on the Genesis just so that Capcom could really take advantage of the business opportunities overall. So, Capcom was very much embedded with Nintendo throughout the entire time I was there.

John Gillin: Sega CD, no. As far as the dynamics between Capcom and Sega, I’m going to talk in generalities. I can’t get into specifics because I just don’t know, but my understanding at the time was that the owner of Capcom had family relationships, I mean this goes back generations, but family relationships with the folks that owned and ran Nintendo. There was a very, very strong loyalty between the two companies and Capcom was going to forever be a Nintendo licensee. It wasn’t until there was this massive success of Street Fighter II that Capcom really ended up having to go to Sega in order to try to optimize its business opportunities. But Capcom was always going to be deferential to Nintendo. If you go back and you look, at least back then – it’s different now – but if you look back then, Capcom really didn’t come out with many Sega games at all just because its primary loyalties were to Nintendo, and Nintendo valued Capcom a lot as well for its dedication and loyalty. So, there was a really good relationship there. I don’t know whether Capcom went to Nintendo and said, “Would you mind if we released this on Sega just so we can optimize our business fortunes?” I don’t know whether there was ever any permission put out by Nintendo, but I would not be surprised if there were discussions between Capcom and Nintendo about the opportunity to release Street Fighter II on the Genesis just so that Capcom could really take advantage of the business opportunities overall. So, Capcom was very much embedded with Nintendo throughout the entire time I was there.

And I remember when we announced that Capcom was coming out with a Genesis version of Street Fighter, that exploded a lot of journalists’ heads. They were all like, “What? You’re doing what?” because they knew about that loyalty between the two companies. But yeah, it really surprised a lot of people.

Sega-16: Yeah, I remember that for the longest time we never expected to see Capcom and Konami, those big licensees for Nintendo, we didn’t expect to see them releasing games for anyone else. And then when they finally did, we were super surprised because no one ever expected to play Street Fighter on the Genesis or Castlevania or games like that. And it was really great to see them expand. It was a great time that you had all these companies just putting out all these incredible games for both consoles.

John Gillin: Yeah, it was amazing how many different platforms were out there. But you ask about the Sega CD and whether Street Fighter was ever going to come out. I think one of the biggest issues for Capcom was that… and I know that the two systems are very different. I don’t know how much, if any, efficiency you can get from porting a game from a Nintendo platform to a Genesis platform. I think at the end of the day also, I think Capcom was still going to dedicate a lot of its R&D and development to creating games for Nintendo, and any of those porting operations do take time and money. And I think that they were willing to put forth a little bit, but I don’t think Capcom at that time ever really came out with any original IP for Genesis. I think a lot of it was just a couple of ports that they knew that they could do well with. And that may very well have gone back to loyalty to Nintendo and just saying, “You know what? We could probably do well on Genesis, but we’ll do what we can in order to keep consumers happy and also make a lot of money, but we’re not going to go full force and support Genesis, or, for that matter, Sega CD or 32X or whatever the iterations were for Sega.”

Sega-16: After the Genesis launched, owners did get to play Capcom games, but they were licensed by Sega and reprogrammed. Sega did the ports of like Ghouls N’ Ghosts, Forgotten Worlds, Final Fight CD. So, you got the Capcom games, but they were licensed by Capcom to Sega, and Sega did the porting job. Until Capcom became an official licensee, there were several games like Strider and Mercs – they were all arcade ports. They weren’t any original titles. So, for the first three or four years, what you got were Sega ports, and they were great ports; they were great versions, but they were released by Sega, the Sega label, because Capcom wasn’t a licensee.

John Gillin: Gotcha. That makes a ton of sense, and I appreciate you knowing the space better than I remember. Yeah, thank you for reminding me about that. It was really interesting about the loyalties, and there may have been legal considerations as well; I don’t know. I’m not sure what was going on in Japan between all the companies, but it may be that Capcom just didn’t want to ruffle the feathers of Nintendo. And so whether it was a legal understanding or it was a cultural, loyal type of relationship, I’m not sure, but those kinds of situations were very new concepts to me in the business world.

Sega-16: So then, from Capcom you went to Sega, and I read that your position at Sega was created specifically for you?

John Gillin: That’s correct. I’d been at Capcom for two years and obviously had a pretty good level of success. When I was working at Del Monte, I overlapped briefly with Diane Fornasier, who eventually ended up at Sega and was running the marketing for them. And it was at that point that I received an outreach from her in which she said, “Hey, how have you been? How’s it been being out of Del Monte?” During our conversation, she expressed interest in bringing me over to the Sega team. I said I would be very open to that. At the time that I was at Capcom, I was a director of marketing, and I wasn’t at a point where I could move up to a VP spot. At the time, Sega didn’t have director-level positions in their marketing department. In order to entice me to join them, they decided to create that level within the marketing department so that they could have a place for me to land if I were to come over. And so they did. And it was a fantastic opportunity for me. It was so much fun to go from Capcom to Sega.

Now granted, I took a lot of flak from folks at Capcom and people I knew in the industry. They were saying, “I can’t believe you’re going from Nintendo to Sega.” It was a form of rebellion and betrayal that people just couldn’t comprehend. But I just said, “Hey, look, Sega’s doing a great job. They’re number one in the market right now. I love what they’re doing, and I think it’s a great opportunity for me, both personally and for my career. And so I’m going through with my decision.” I’m very happy I did. I ended up going over to Genesis, and initially my assignment was to run the Genesis hardware business as well as all the software that Sega was putting out on the Genesis platform.

That was a fun time, especially in an industry like that, in which you’re really dependent upon both sales streams, whether it’s the hardware sales stream or the software sales stream because they’re pretty well intertwined… just the challenge of having to initially manage the growth of that sector and then having to manage its decline as we were preparing to move into the Saturn. That takes a lot of interesting strategic planning and foresight in order to manage down inventories and resources as Genesis begins to go away and Saturn starts to rise. It was a fascinating exercise from a business standpoint. It was also exciting personally.

Sega-16: When you arrived at Sega, I think the Saturn was already on the horizon, right? I think the 32X was either out or about to be released. I can guess that Sega’s beginning to change its focus to the next generation of hardware, but you still have this massive installed base of Genesis consoles. So, in terms of marketing, how much life did you see left in the Genesis at that time? Was it still something that you could get strong sales out of or was it something that you had to begin to wind down?

John Gillin: Great question. It was really all of the above because Genesis wasn’t going to last forever; we all knew that. Saturn was a more expensive and more robust operating system that was really going to appeal to a different class of gamer, ones who were looking for cutting edge graphics, looking for new experiences in video gaming. Genesis, while it was no longer going to be the primary hardware unit in homes going forward, still had a tremendous place in the market, which we began to position as kind of second machine, the hand-me-down machine to younger kids in the household. And there were still opportunities, so the games that we were developing may not have been quite as edgy but would appeal to a little bit of a younger audience.

John Gillin: Great question. It was really all of the above because Genesis wasn’t going to last forever; we all knew that. Saturn was a more expensive and more robust operating system that was really going to appeal to a different class of gamer, ones who were looking for cutting edge graphics, looking for new experiences in video gaming. Genesis, while it was no longer going to be the primary hardware unit in homes going forward, still had a tremendous place in the market, which we began to position as kind of second machine, the hand-me-down machine to younger kids in the household. And there were still opportunities, so the games that we were developing may not have been quite as edgy but would appeal to a little bit of a younger audience.

And let me explain the rationale behind the 32X in more detail. If you recall, the 32X was an accessory that a Genesis owner would plug into the cartridge slot of their console. Buried in the 32X was a chip set that expanded the processing power of the console, ostensibly from 16-bit to 32-bit. Sega developed this piece of hardware to help bridge the gap between the 16-bit category and the upcoming 64-bit category, of which the Saturn, Sony PlayStation, and Microsoft Xbox were entering. Part of the strategy was to keep kids playing the Genesis system and help slow the decay in hardware system sales as consumers began saving their money to purchase the next generation consoles. It also allowed Sega to dominate the consumer press with new news rather than the press’ focus on the future launches of the 64-bit consoles. At the end of the day, 32X did not fulfill expectations, and Sega ended up with a lot of extra inventory in hardware and associated software.

So, I mentioned to you the 11 to 17 year olds. They were still kind of a core consumer group we were going to go after for Saturn. And again, it was about this point in time that video gaming began to move out of an adolescent kind of target and more into a young adult, where there were more and more kids taking these machines to college or moving out of the house and getting a job and taking the machines with them. This is where we really began to see the saturation of the gaming audience. Kids who had been playing for five, six, or seven years and now moved out of mom and dad’s house but were still playing, still looking for it as a stress release and entertainment diversion, and so the upper end of the age limit began to expand out. And that’s where things like Saturn and other, pricier consoles were going to have a lot of appeal. Genesis, because it was an older technology, still had a tremendous audience with younger kids as a hand-me-down, so we were able to long-tail the decline in that particular category because there was just so much latent opportunity there. And it was about that point in time, it was about midway in my time at Sega, that we started coming out with Sega Kids, where we could position video games as an educational vehicle in order to teach kids.

Sega-16: The Sega Club?

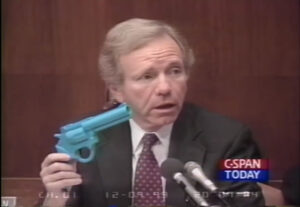

John Gillin: Sega Club, that’s right, and I was not involved with that at all. That was a separate business initiative run by somebody else on a different floor, so I really wasn’t exposed to it that much, but it still made perfect sense that we could really focus on helping to broaden the appeal of the machine. Now granted, the other thing about the Sega Club is that this was also in the heat of the moment when we had game and industry executives being called up on Capitol Hill because of the “violence in video games” issue. Senator Joe Lieberman was making this a huge issue, and there were a lot of hearings about the “rampant, uncontrollable, violent nature” of video games and how it was horrible for our kids. There were a lot of offsetting business strategies done in order to try to soften the image of the video game industry. So, Sega Club was one of many, many initiatives that were done to help blunt the cultural attack on the industry in general and Sega in particular. The most important outcome out of all that, though, of course, was the ESRB [Entertainment Software Ratings Board], which, I think, really said to the government, “Hey, you know what? We can regulate ourselves. We don’t need the government stepping in and regulating us.”

Sega-16: I’ve never read anything about when the Senate hearings were going on, when all that came down, of Sega requiring… I know that Sega already had a rating system of its own before that, and it put disclaimers on certain games, but I haven’t read anything about Sega ordering a change in marketing strategy when those hearings began. Was that the case? Did Sega continue with its marketing as is, or did they adjust because of the controversy?

John Gillin: I think there were some adjustments. Granted, Street Fighter II, while it was a depiction of two individuals fighting each other, was a lot milder than what was soon to come out. While we may have raised initial interest in the concept of violence in video games, at the end of the day, it was really Mortal Kombat that was really drawing the focus and the ire of Congress and parents because some of the final moves were, at the time, graphic, bloody and gory. Parents were just saying, “My god, what are my kids watching? Why is that character ripping the spine out of this person?” And that was what really put the whole discussion and debate into overdrive. But the industry as a whole and individual game companies were trying to shield themselves in their own way. At the time, it was like herding chickens. Everybody had a different opinion as to what to do and how to do it. Some companies were saying, “Screw it. These are our First Amendment rights, and we’re going to do whatever we want.” Others were saying, “If we don’t take care of this, then someone’s going to have to do it for us,” and I think it was at that point in time that the alliance came together, the ESRB, where all the major companies said, “You know what? We need to all get under the same umbrella and just do something that is no different than what they do in Hollywood and just have an independent ratings council that will put a rating on these games so that we can really demonstrate that we’re being responsible.”

At Sega, in addition to our senior executives leading the industry initiative to create the ESRB, we had Sega Club. When you run a business, you’re always trying to look for every way possible to create new streams of income, to diversify yourself, so that if one stream of income begins to fade or gets to the end of its life cycle, you’ve got other streams you can focus on. And Sega Club was a great idea in order to appeal our consoles and video games to a younger market. So, going below that previous 11-year-old marketing threshold that we had for our mainstream market but then also appealing to kids in other ways. We had a lot of great licenses. We had Berenstain Bears, and we had My Little Pony. So, we had a lot of great licenses that gave kids an opportunity to play really benignly plotted games where they could enjoy interfacing with their favorite cartoon characters. But then we also began to look at trying to do some games that were a little more educational in focus so that kids could hopefully maybe learn to count a little earlier than they might otherwise be able to if they were on a traditional schooling track. So, we saw a lot of opportunity there, but there are a lot of reasons why that concept didn’t have long-term legs. Over time, as Sega began to move into the years 1996 and 1997, there were a lot of other forces at play that really began to tear the company apart.

Sega-16: Yeah, I can imagine. When Sega transitioned into the Saturn, you could tell that there was an obvious shift in the way it marketed. It wasn’t marketing the Saturn as a continuation of what it had done with the Genesis. It was a new system with a new image.

John Gillin: Exactly. The marketing for the Saturn – it was out of this world, pun intended. You can always look back with 20/20 hindsight, but I think everybody wanted to really make a splash with the Saturn, and I think some of the ads just came off as a little too weird. A lot of that I placed with our ad agency at the time. Our ad agency was full of very creative people, very good at what they did, but agencies suffer from a problem in that once they get big and once they get good and they get well known, they begin to attract other clients. The new clients then say, “Hey, you know, I really love your work. I want to work with you. I want you to do for us what you did for Sega.” There are a lot of creative people in the world, but there’s a very small number of uber-creative people, and when that team has had a number of successes inside an agency, that agency has to show its best stuff to the prospective clients to get the new business. Those really good people will then move to the new client, and Sega gets left with the B-team. I believe we did bring back the A-team for the Saturn launch, but it just… they went way too far out into just a weird world instead of enhancing and building upon the irreverence of the previous communication strategies. The new brain ads took irreverence into a new direction, but it was an uncomfortable, dissonant one that had a hard time connecting with our broad consumer audience. For me personally, I wasn’t there saying, “God, this is going to be it. This is going to really revolutionize the industry.” Yeah, I wasn’t there.

Sega-16: As the Saturn went on through 1995, 1996, and into 1997 the market changed. Nintendo came out a little bit later with its console, and Sony really did well with the PlayStation. When you arrived at Sega, the Genesis was on top and it was selling really, really well, but by 1996, 1997 it’s a whole different world. What was it like having to market a console that’s now facing an uphill battle, plus what was going on within Sega, the changes and the things that were happening? How did that affect your ability to effectively market that hardware?

John Gillin: That’s a very good question, but I had been at Sega for about a year working on the Genesis business. By that point in time, the Saturn project was a skunkworks project and nobody in the company, outside of the limited team that was working on it, nobody in the company was allowed to know what was going on. So, we knew there was this new project, and we knew there was this new machine that eventually got named, so we knew it was called the Saturn project, but beyond that, none of us knew anything about it. Nothing. It was left in the hands of our most talented marketing people, and the team essentially consisted of a handful of marketing people, the executives, and the ad agency, that was it. So, all of us were kind of on the outside looking in.

I had been running the Genesis for a little over a year, and our Sega Sports guy left the company. Sega Sports was a really big piece of our software sales. The VP of marketing at the time, Mike Ribeiro, came to me and said, “Hey, I know you love sports. Do you want to take over Sega Sports?” and I said, “Hell yeah!” I love the Genesis, and I love sports, so for me to be able to go run Sega Sports was heaven. So, I moved over there and I became more focused on the lineup of sports games rather than anything having to do with hardware. Ostensibly, I was responsible for any title that came out from Sega that had to do with sports because I managed all of the relationships with the leagues. I was the one who interfaced with all the different third party license folks at each sports league, so I was supposed to have complete control over all the sports games, but as sports games came up as part of the lineup of titles for Saturn, for example, I was not allowed to look at the sports games on Saturn because again, Saturn was such a sensitive skunk works project that I got cut out of that. They weren’t letting anybody from outside that real core team have any say or exposure. I was disappointed but understood and said, “Okay, you know, that’s fine. I’m a team player and I’m not going to squawk about it.” I think I probably moved to sports… let me see, that would have been probably around 1995. Somewhere around early to mid-1995 I moved over to the sports role.

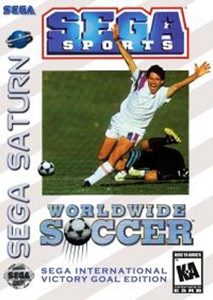

Sega-16: The Saturn had some pretty good sports games that unfortunately don’t get the kind of recognition they deserve. I remember I really enjoyed NBA Action ‘97. I really liked the NBA Action series, but the Saturn version of NBA Action I really enjoyed. World Wide Soccer was a really good game, as was Daytona.

John Gillin: World Wide Soccer was a good one. Daytona was great. Yeah, Daytona was another one of those arcade hits that had done very, very well, and it ported over pretty faithfully to the Sega Saturn. That was, I think, probably our best-selling sports game, but World Wide Soccer was another good one. Sadly, we were unable to get a FIFA license because FIFA had their relationship with EA, and there were really no other soccer federations that would have been worth engaging with at the time, so we just generically called it World Wide Soccer.

John Gillin: World Wide Soccer was a good one. Daytona was great. Yeah, Daytona was another one of those arcade hits that had done very, very well, and it ported over pretty faithfully to the Sega Saturn. That was, I think, probably our best-selling sports game, but World Wide Soccer was another good one. Sadly, we were unable to get a FIFA license because FIFA had their relationship with EA, and there were really no other soccer federations that would have been worth engaging with at the time, so we just generically called it World Wide Soccer.

Sega-16: You left Sega while the Saturn was still out, right?

John Gillin: I did. I think it was probably around February of 1997.

Sega-16: Was it because of what was going on in Sega, or did you just decide to move on?

John Gillin: No, I was let go in a reduction in force action. Sega had already gone through a couple of rounds of layoffs, and by the time February of 1997 came around, I became another casualty. Sega eventually got to a point where it was down to, I believe, just the core accounting staff; it got so bad, they weren’t really aggressively pushing any hardware. I think they had sales teams that were still calling on accounts, but the company really just imploded. When I was there, I think at our peak, we had maybe 1,100 employees throughout the U.S. Maybe not when I left but soon thereafter, I think the headcount had gotten down to about 85 or 90 people.

Sega-16: Wow.

John Gillin: Yeah, it was… it was ugly. It was really ugly.

Sega-16: I didn’t know that that’s how you left. I thought that you had moved on, on your own. That fits with everything that I’ve heard and from people who were there at the time.

John Gillin: : It was not a good time for Sega. Actually, it was horrible. And, you know, my tenure there was about three years, and to have been there for such a short amount of time and to watch that company go from really doing so well and then to go to where it was by the time of my departure just… you know, it was sad. And we had so many good people that were leaving. There were a number of theories as to why the company started to fall apart, but I’m sure you’re familiar with most, if not all of them. It was tough, and then when Tom Kalinske and Paul Rioux left, the floodgates opened. Then we got new people in who I never clicked with. I just didn’t think that they had a good feel for our company or the business. Then there were, of course, just the external dynamics, between Sony coming out and then Microsoft coming. I mean, it just got to a point where if you weren’t really on your A game and you didn’t have everybody pulling the rope in the same direction, you were bound to just get slaughtered.

Sega-16: Tom Kalinske recently did an interview where he talked about how he left. I know, I first interviewed him in 2006 and I’ve spoken to him a few times and we’ve talked about that, but it wasn’t until after he left Sega that he learned why things like Sega of Japan’s attitude towards him had changed. Like, instead of being given the kind of freedom that he had had before to make the decisions, he was being restricted more and more and being cut out of the decision-making process. He said it wasn’t until after he left that he found out why that was, and he said that it was because he had heard that Sega of Japan, the board of directors, really were getting beaten up by Hayao Nakayama because Nakayama would tell them, “Why can’t you do more like Tom is doing? Why can’t you turn things around?” and they were getting beaten. He says that he guesses that after months of hearing that you get to the point where whoever that Tom guy is you really hate him. So, the board kind of forced him out. They didn’t fire him but they made it so that he wanted to leave.

John Gillin: Yeah, and I read that somewhere else and that would not surprise me. I mean, the tough thing is every culture values pride to one degree or another. The Japanese are extremely proud. They work very hard. They’re very, very proud people, and when you have a company like Sega that had been in the market so long that had always played a number two position to Nintendo… I mean, a vast number two position. They were a long number two behind Nintendo. Cultures like Japan, there are ways you do things and there are ways you do not do things. It’s a very structured culture, and when you are constrained in your ability to do anything, whether it’s live your life or how you do your business, that’s just the way it is. That’s kind of the natural balance that plays out there.

Then you come to the United States where we really are a wild west, where we reward individuality, reward craziness. When you have this upstart American division of a Japanese company that is so small that the Japanese company doesn’t even really pay much attention to it because they’ve got our own battles to fight there at home in their market. All of a sudden, this little, teeny upstart office starts doing some really pretty cool stuff for the American market, and then you’ve got things like the Sega Scream and all this really irreverent advertising and positioning. Then when, “Oh my God! Look at that, the company’s doing really well! Oh my God, the company’s number one in their country!” To one degree, you can say, “God, that’s fantastic that at least one division of your company is doing well.” At the same time, though, you’re right, it creates a lot of internal questioning, like, “Why can’t we do that here in Japan?” But I think for the Japanese, they were really boxed in on a number of different levels in their ability to do that kind of just super crazy marketing, and yes, that creates a lot of resentment.

And that story, I’ve read that story before. At the end of the day, after thinking about that, I think, “Yeah, you know what, that makes sense. That does not surprise me,” and it really is too bad because I think we could have done more. I think the Saturn launch really also helped accelerate the decline of Sega. There were a number of issues related to distribution of the first shipment of the games. There were pressures that were put on that didn’t need to be put on, or at least perceived pressures based on competitive actions that were thought to be coming. I mean, it was just a huge car wreck in so many different ways.

In May 1995, at the very first Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) in Los Angeles, everyone in the industry was looking forward to competing launches of the Sega Saturn and the Sony PlayStation later that year in September. However, Sega had a surprise up its sleeve, and during its presentation to trade show attendees and press, Tom Kalinske announced that the Sega Saturn was available “now” at $399. Sega had secretly shipped an advanced allocation of consoles and games to select retailers the night before the speech. The room went silent and then erupted in applause and cheers. Granted, we were way behind on our manufacturing goals, but the idea was to seed the market early and create demand through scarcity marketing. Sounds familiar, but unlike my previous experience with this strategy, I was not involved in this decision.

Next up was Sony PlayStation, and a lot of us in the audience thought, “Wow – how is Sony going to follow that Sega bombshell?” One of the Sony executives got up and explained how great the Sony PlayStation was going to be. He then said that Steve Race, then the VP of Marketing for Sony, had an important announcement. Steve walked to the podium and only said “299”. Mic drop. The place went wild. Advance speculation had said the PlayStation was going to price out at $399 or maybe optimistically $349. But $299? Sony had just undercut Sega’s strategy of an early ship announcement with a price point $100 below Sega. And in the world of video game consoles, where most purchases were made by parents, a $100 price difference was going to destroy Sega’s entry, which was never going to quickly match that price point because of a high cost-of-goods.

I sat there and muttered, “Oh shit.”

In my opinion, it seems that, and I’m not an engineer, so I may be speaking out of context here, but the Saturn, from what I heard talking to engineers, was a very, very well-designed, and engineered game console. The problem was it was too well-designed. There was more stuff put under the hood than needed to be put there, and as a result, it kept the price point high because the cost of virtual design was very high at the time. The ability to render items in 3D was a whole new paradigm in game development and as a result, it required more costly CPUs and a lot more investment in game development. That created an inability to initially be able to compete on price because hardware is already a tough category to try to compete in, but when you’ve way over-designed or over-engineered your hardware, you really limit your ability to be able to compete on price.

Sega-16: Every time I talk to someone who was there at that era, there’s always that tone of like, “You know, it could have gone different, it should have gone different,” and I remember getting the Saturn at launch.

John Gillin: Where did you buy it?

Sega-16: I bought it at Electronics Boutique. I had originally gone in to buy a 32X. I had the $170 to buy a 32X, and when I walked in, they were putting out the Saturn boxes, the games, and the display; and I was like, “What’s this? I thought this didn’t come out until September.” No, it’s out now! And I was like, “Oh my God!” The thing is, here in Puerto Rico, it was $430. So, I didn’t buy the 32X. I didn’t even have half the money to buy a Saturn. One of my friends said, “Well, let’s go half and half. If you can get half of it, I’ll put the other half, and we’ll alternate days, like custody of a child, you know?” We couldn’t buy any games though! So my other friend said he’d buy Daytona, Panzer Dragoon, and Clockwork Knight. So, we made that arrangement, and then I bought out my other friend, because he needed money for other things, so I ended up getting the Saturn.

John Gillin: That’s great. I love this. That’s so cool.

Sega-16: I remember going to Electronic Boutique and Toys R Us, and I would look at the PlayStation section and then look at the Saturn section, and honestly, there were times where I would look at the Saturn section, and ask “What’s going on? Where are the games? What’s happening? What are they doing?” because having been a Sega fan since the Master System, and seeing how Sega just got better and better through the end of the Master System and into the Genesis with the Saturn, it was like, what happened? And you could see it when you walked into the stores. You could see there weren’t as many standees, there weren’t as many posters, like something was holding it back. Of course, we didn’t know what was going on. We didn’t know anything about the market, about business, sales, things like that. I remember there was Genesis promotional stuff everywhere, and with the Saturn, it was very limited.

John Gillin: What a great perspective you provide. Yeah, it was tough. As you know, there wasn’t enough inventory for a full launch during the time frame that the Sega Saturn team had identified at E3, so instead of limiting the launch geographically, say all retailer locations west of the Mississippi, they decided to do a launch by retailer, to which Kay Bee Toys said, “You know what, you will never, ever see your product in our stores again” and they held to it; they never, ever took the Saturn and deemphasized any support for our other Sega products. I think they hit us on Genesis and other games and platforms because they were so pissed off that they didn’t get a bite of the apple for that initial Saturn launch. It’s just all those kinds of things. There were so many different moving pieces with that launch that at the end of the day, there were too many straws on that camel’s back, and the camel couldn’t take it anymore.

Sega-16: I want to thank you for sharing your experiences. It was really great to hear your perspective, I love to hear the experiences of people who were there because, to me, it’s the next best thing to being there, having been a follower through all those years and everything.

John Gillin: Thank you! The pleasure’s all mine.

Our thanks to Mr. Gillin for taking the time for this interview.

Recent Comments