Innovation is the creation of the new or the re-arranging of the old in a new way.

-Michael Vance.

The words of the famous communicator and management guru sum up nicely what it was like to work at Sega Technical Institute. Unlike any other place in gaming at the time, STI was a place that not only cultivated innovation and creativity but held it as its mantra. If you were a young designer, artist, or programmer, this was the place where you wanted to work.

What made the Institute so different from other development houses of the era is that it was specifically created to work outside the corporate structure of its parent company. Employees there were not told what to create or assigned licensed shovelware to be turned into a quick cash run. No, those lucky enough to be at the Institute were given complete creative freedom to develop games, with a hefty budget and almost no interference from management. So great was the confidence placed in this elite group of individuals that Sega entrusted them with the future of the company’s mascot and biggest star, Sonic The Hedgehog. In an industry today where so many smaller and talented development houses are being eaten up by bigger publishers, only to be either dissolved or have their staffs walk out, it seems almost alien to learn that the biggest software house of the 16-bit era actually promoted such independence.

What made the Institute so different from other development houses of the era is that it was specifically created to work outside the corporate structure of its parent company. Employees there were not told what to create or assigned licensed shovelware to be turned into a quick cash run. No, those lucky enough to be at the Institute were given complete creative freedom to develop games, with a hefty budget and almost no interference from management. So great was the confidence placed in this elite group of individuals that Sega entrusted them with the future of the company’s mascot and biggest star, Sonic The Hedgehog. In an industry today where so many smaller and talented development houses are being eaten up by bigger publishers, only to be either dissolved or have their staffs walk out, it seems almost alien to learn that the biggest software house of the 16-bit era actually promoted such independence.

Humble Beginnings

Sega Technical Institute was the brainchild of Mark Cerny, a gaming veteran who had broken into the field in 1982 at the tender age of seventeen and Sega of Japan (most notably Yutaka Sugano of Shinobi). Cerny wanted a career in video games, and he initially found himself working at Atari. There he designed the monster arcade hit Marble Madness (the Genesis version of which he hates). Realizing that great games could be done with small teams of people, Cerny decided that it was time to move on, and he set up meetings with Sega of Japan head Hayao Nakayama and company founder David Rosen. Sega agreed to fund his next arcade project, and Cerny quickly got to work. As time passed though, he soon found that things weren’t moving as fast as he – or Sega – wanted, and he was approached by Nakayama about canceling the project and coming to work directly for Sega in Japan. The arcade powerhouse was about to release the Master System in an attempt to wrestle the market from the dominant Nintendo, and Nakayama felt that Cerny’s design experience could be a big help in creating software for the new platform. Cerny agreed and was soon on his way to Tokyo.

What awaited him was much more than culture shock; it was corporate shock. Unlike Atari’s small teams, Sega essentially had one big bunch of forty-odd people working on games in a single room. Divided into groups of one or two employees per game, each tiny task force was given around three months to come up with a game. This might seem like insanity, until you consider that this cadre of talent included the minds of Rieko Kodama and Yuji Naka. Cerny learned much during his time at Sega, and he sought to push the envelope of what the Master System could do. During one of his many trips to Tokyo Disneyland, he saw the Michael Jackson 3D attraction Captain Eo, and it occurred to him that 3D in games hadn’t really seen any advancement up until that point. He persuaded Sega to come up with a liquid crystal prototype, and desperate in its attempts to combat Nintendo, Sega agreed. The SegaScope 3D Glasses were released as part of the Master System’s large line of first party peripherals, and six games were eventually made available for it. Even Yuji Naka himself tinkered with it, though his tunnel demo was never made into an actual game.

Over the next few years, Sega released the Genesis, and Naka went on to join Sonic Team in the creation of the massively popular Sonic The Hedgehog. Cerny, who had been consulted by Sonic character artist Naoto Oshima during the famous hedgehog’s creation, learned that Naka and other members of Sonic Team had left Sega of Japan, reportedly because of a lack of proper compensation and recognition within the company after the game’s success (Naka was upset with the seniority-based pay policy). Cerny had come to the American branch of Sega in 1990 to make his earlier vision of small team development a reality, and after learning of Naka’s departure, he saw an opportunity to bring him over to the U.S. Sega of America’s president Michael Katz made it a priority to increase the U.S. side of Sega’s game development, citing the over-reliance on Japanese software that did not fully cater to American tastes. To this end he, along with executive vice president Shinobu Toyoda, gave Cerny the green light to create his studio, which he called Sega Technical Institute. When he was finally ready to begin, one of Cerny’s first actions was to contact Yuji Naka and offer him a place at the STI.

Yuji Naka’s departure from Japan has been an issue of controversy over the past two decades. It was speculated that he left because he was unhappy with his financial compensation, especially after the success of the first Sonic title. Cerny clarified the situation to us via email about how the famed programmer arrived at STI. “After the first Sonic shipped,” Cerny details, “he quit. He was tired of working at Sega. One big issue was that even though Sonic was immediately a big hit, he got a lot of grief for having missed the schedule (he took fourteen months rather than ten, I believe) and head count (total head count was 4.5 people rather than three, I believe). I think he also felt unappreciated on many levels, including financially. I believe his base salary at the time was about $30,000, though he did get bonuses.”

Though he was largely responsible for the greatest success Sega had ever had, Naka still made the decision to leave the company that had been his home for years. Even with his new-found recognition, things weren’t going the way he expected. “This was the summer of 1991,” Cerny continues. “I’d been setting up and running Sega Technical Institute, so I was in Japan quite a bit. I was shocked to hear he’d left, so I found out where he lived and dropped by. His apartment was in a rather dingy building, but it was perfect for him because it was just a few minutes walk from the office. At any rate, I heard his long list of issues and started thinking about how to resolve them. And of course financial was part of that.” Thus, four months after Sonic’s debut, the acclaimed programmer agreed to join his friend at STI. With him came another Sonic Team alumnus, Hirokazu Yasuhara, who had designed the gameplay and stages for much of the original Sonic The Hedgehog. (Ironically, Yasuhara would once again team up with Cerny many years later at Naughty Dog to work on the Jak & Daxter series.)

Though he was largely responsible for the greatest success Sega had ever had, Naka still made the decision to leave the company that had been his home for years. Even with his new-found recognition, things weren’t going the way he expected. “This was the summer of 1991,” Cerny continues. “I’d been setting up and running Sega Technical Institute, so I was in Japan quite a bit. I was shocked to hear he’d left, so I found out where he lived and dropped by. His apartment was in a rather dingy building, but it was perfect for him because it was just a few minutes walk from the office. At any rate, I heard his long list of issues and started thinking about how to resolve them. And of course financial was part of that.” Thus, four months after Sonic’s debut, the acclaimed programmer agreed to join his friend at STI. With him came another Sonic Team alumnus, Hirokazu Yasuhara, who had designed the gameplay and stages for much of the original Sonic The Hedgehog. (Ironically, Yasuhara would once again team up with Cerny many years later at Naughty Dog to work on the Jak & Daxter series.)

Back in Japan, Nakayama had no problem with the decision to create a new studio. He knew that the 16-bit generation would either make or break Sega in the home market, and he was willing to pull out all the stops. “Nakayama clearly understands that when in Rome, you should do as the Romans do,” Toyoda once remarked. “At Sega of America we have autonomy.” Though Japan would offer feedback and assessment of the designs coming from the Institute, it would now be SOA’s new president, Tom Kalinske, and Toyoda who would have the final word on a project’s future. Everything seemed to be in place, and Cerny’s vision was finally about to come to fruition.

The plan was a simple one. He would bring over seasoned talent from Japan and have them work with inexperienced Americans in order to give them the opportunity to learn from among Sega’s best minds. This mentoring would unite the best design philosophies from both countries. Toyoda’s comment on autonomy was on the mark, and STI was given almost complete independence in its efforts. So confident was Sega in its elite studio that it was the only development group allowed to do both arcade conversions and original properties. Sonic games would be the main focus, which would help push Sega’s business forward, but the Institute would also be tasked with creating compelling and innovative new titles. Cerny set up shop in Palo Alto, California and quickly began to organize his people into teams.

The staff at STI were given great freedom in their work, and the laid back, non-corporate atmosphere encouraged even the most inexperienced employees to think big. Every Wednesday, Sega would hold lunchtime review sessions for all new products, both in-house and third party. This was perhaps the only part of the creation process that STI personnel disliked, as new projects had to be shown to management for approval, and the almost secretive nature of what went on at the Institute (STI offices actually had security locks that only a few outsiders had access to) meant that few of the higher-ups knew what to expect. Convincing the executives to give a new property a chance could be difficult, and most presentations became more flash than substance in an effort to impress. In the end though, the final word always came from Shinobu Toyoda, so STI staff tended to direct their presentations at him. More often than not he gave them the benefit of the doubt.

Work began in 1990 on the first game, Dick Tracy, followed early the next year by Kid Chameleon. With original titles underway, Cerny began to look towards creating a sequel to Sonic The Hedgehog. Two of the three people who had been key to the first game (Nashima remained in Japan) were on their way to STI, so Cerny approached management about getting one underway. Their answer shocked him. “No, it’s much too soon,” they said. Baffled but content to continue with the new properties that were coming along nicely, he returned to work. That November, however, he got a frantic call from his superiors. “We do need that game, and we need it now.” Two months had been lost from the game’s proposed schedule, and Cerny had to scramble to get a team organized to complete it on time.

Compounding the timetable troubles were personnel problems. The American side of STI was already hard at work, but the Japanese hadn’t arrived yet due to visa complications. Differences in language and culture added to their woes, but the team pressed on. Despite the fact that both sides were on friendly terms, there were still some grave contrasts in their working styles. The Japanese were among Sega’s top developers, and it was difficult for the relatively inexperienced Americans to keep up. They also had an entirely different work ethic, and many worked throughout the night and even slept in their office cubicles! Tension mounted, and by the time Sonic 2 shipped, Naka had had enough. The group was broken up into smaller units, with the Americans dedicating themselves to mostly original titles, and the Japanese concentrating on Sonic sequels, like Sonic 3 and Sonic & Knuckles. Former STI member Tim Skelly recalls the difficulties. “Everyone attached to to Sonic 2 ultimately worked for Yuji Naka. I think Naka would have been much happier if he was working with an all-Japanese team, but just because of the language barrier and some cultural differences. Imagine how you would have felt at that time if you were creating a Superman comic book and you were given a manga artist to do the artwork. The differences weren’t as extreme as that, but you get my point.”

This didn’t mean, however, that the two sides never again collaborated. There has been great speculation regarding the separation of the teams, and the general assumption is that the rest of STI’s post-Sonic 2 days were spent with two different units – American and Japanese – working under the same roof but never together. This is not entirely accurate. Though the Japanese had their games to work on, which fulfilled the Institute’s mandate of creating Sonic sequels, they were often joined by their western counterparts. For example, graphic artist Chris Senn did concept art for Sonic & Knuckles, and composer Howard Drossin provided the soundtrack. Also, STI’s final project, Die Hard Arcade was done by both Americans and Japanese AM1 members. There was no set policy for integrating or separating the two teams, and management encouraged the mixing of people and resources.

Naka himself was done with the Institute, and he took a well-deserved break after completing Sonic & Knuckles, returning to Japan a few months later to begin working on a game that would take Sonic Team in a different direction: NIGHTS: Into Dreams. During his time off, Naka had become acquainted with the Saturn hardware, and he now felt it was time for Sonic team to move off from its namesake and into new properties, as well as push the Saturn’s 3D capabilities further. NIGHTS presented the perfect opportunity for this. Sega gave Naka’s group complete freedom in designing and building this new game, and the result was the first 32-bit title created at STI. NIGHTS was a hit, though it wasn’t enough to save the Saturn.

Winds of Change

Shortly after Sonic 2‘s massive success, Cerny decided to leave the Institute for greener pastures even though Sega still had complete confidence in his abilities. He was succeeded by another Atari veteran, Roger Hector. Hector was no stranger to the game industry either. He had also gotten his start at Atari, back in 1976, and worked on such classics as Battlezone and Warlords. He moved on to Electronic Arts, where he was part of the team that did Skate or Die! and Jordan vs. Bird: 1 on 1. Eventually, he ended up at Disney Interactive where he worked on Castle of Illusion Starring Mickey Mouse. It was from there that he made the jump to STI as its new General Manager. It took him a short while to grow accustomed to the new atmosphere, but he quickly adapted to its style. Hector never really tried to “rock the boat,” and under his guidance the Institute continued its practice of integrating its members when needed. To Hector, the problems between the two sides wasn’t anything out of the ordinary. “It is normal for there to be a bit of tension between talented team members and competing project teams,” he recently told Sega-16, “even if they work for the same company.” Furthermore, he had no wish to divide the Institute’s talent in to autonomous cells. “STI had three to five project teams at any given time, and the make up of each team changed throughout the project’s progress. Sometimes a team would be all Japanese or all American, and sometimes they would be blended. It depended on the needs of the project and who was available.”

Shortly after Sonic 2‘s massive success, Cerny decided to leave the Institute for greener pastures even though Sega still had complete confidence in his abilities. He was succeeded by another Atari veteran, Roger Hector. Hector was no stranger to the game industry either. He had also gotten his start at Atari, back in 1976, and worked on such classics as Battlezone and Warlords. He moved on to Electronic Arts, where he was part of the team that did Skate or Die! and Jordan vs. Bird: 1 on 1. Eventually, he ended up at Disney Interactive where he worked on Castle of Illusion Starring Mickey Mouse. It was from there that he made the jump to STI as its new General Manager. It took him a short while to grow accustomed to the new atmosphere, but he quickly adapted to its style. Hector never really tried to “rock the boat,” and under his guidance the Institute continued its practice of integrating its members when needed. To Hector, the problems between the two sides wasn’t anything out of the ordinary. “It is normal for there to be a bit of tension between talented team members and competing project teams,” he recently told Sega-16, “even if they work for the same company.” Furthermore, he had no wish to divide the Institute’s talent in to autonomous cells. “STI had three to five project teams at any given time, and the make up of each team changed throughout the project’s progress. Sometimes a team would be all Japanese or all American, and sometimes they would be blended. It depended on the needs of the project and who was available.”

As development of Sonic 3 began, the first original STI game was completed. Kid Chameleon was a project that, according to senior programmer Steve Woita, had faced an uphill battle for acceptance from the marketing department. Hired by Cerny, Kid Chameleon had been Woita’s first major project after helping finish up Sonic 2. “I had way more pressure on me working on Kid Chameleon,” he recalls, “because the game was unknown at the time, so we had to prove to marketing and everybody else that we thought we had a good game our hands. It’s always extremely difficult to do an original game idea and hardly any of them make it to the market place, so there was extra pressure because nobody outside of our development group knew what we were doing and if it would sell.” A sequel was eventually planned – in fact, the entire development team was rested and ready to begin work, as it had all the tools ready to do so. Unfortunately for them, Sega had more interest in getting the next sequel to Sonic to market in time for the holidays.

Despite Naka’s perfectionism and fierce protection of the character, he was quite aware that he could not create every Sonic game. For this reason, the American side of STI handled the first offshoot of the series, called Sonic Spinball. When it became clear that the next installment in the popular franchise, Sonic 3, would not ship in time for the ’93 holiday season, Sega went with the spinoff. The marketing department wanted a game centered on the popular casino stages from the first title, so designer Peter Morawiec proposed a pinball game. His demo was quickly approved, and his team was given a mere nine months to complete the project, without any help from Sonic Team. Undaunted, Hector reassured his people that the game would be done on schedule and hired additional programmers Lee Actor and Dennis Koble of Sterling Silver Software (later called Polygames) to get it done. The pair had worked with Hector before, and he was quite confident in their abilities. Polygames handled around 90% of the programming, while STI members handled the graphics, design, and music. Even with all this additional help, Morawiec lamented the lack of input from the people who created the famous hedgehog. “I sometimes wished that we had more Japanese artists on Spinball,” he commented, “because I found the disparity in art styles throughout the game pretty jarring. We had only one artist from Japan (Katsuhiko Sato) who did a couple of great stages — geometrically clean, colorful, and very Sonic-like — but those stages don’t quite match most of the other art in the game. It’s not bad art, but it’s inconsistent and just not as tight.”

An interesting note about Spinball is that the theme song that plays when the game is booted up is not the one initially intended by STI. Shortly after the first Sonic shipped, Masato Nakamura — the man responsible the music for the original game and lead singer of the Japanese band Dreams Come True — became quite famous in his native country. Sega approached Nakamura to do the music for Sonic 2, but the singer had upped his asking price considerably. Since he and his band owned the rights to the music used in the first game, Sega had been forced to look elsewhere for a soundtrack. The Spinball team was unaware of all this and used the original Sonic theme at the start of their game. Development was completed and the bunch held a party to celebrate. Some of the Japanese staff working on Sonic 3 stopped by to chat, and Hirokazu Yasuhara came in and saw the opening sequence. When he asked how they had talked Sega into paying for the rights to the song, he received a roomful of puzzled stares. Everyone had assumed that all the music belonged to Sega, and with the game on its way to manufacture, the song would now have to be changed at the last minute. “Well, no one had told us about this, and we had used the original music.” Remarked former STI level artist Craig Stitt, “Howard, our music guy, quickly ran to his little room and started writing a new piece of music. At about midnight that night we released a NEW gold master version of the game, this time with our own original theme song.” Thus the song was swapped out in time, and Spinball made it out to stores on schedule.

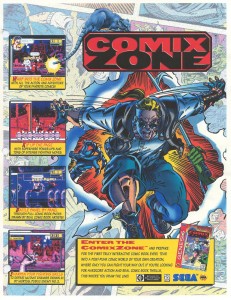

Though it was treated somewhat harshly by the press, Sonic Spinball sold very well and further cemented the reputation of STI developers for creating new experiences. They next turned their attention to what would eventually become the most famous of the American-made games, Comix Zone. Reportedly, there were more than a few comic book fans at STI, and they frequented the local shops for their monthly fixes. Peter Morawiec sometimes joined them, and from these trips he began to envision a game where the player actually went into a comic book and fought his way out. He had whipped up a demo to show management but was dismayed when it had been put on hold in favor of Sonic Spinball. Once that title was out the door, however, STI featured Comix Zone in its next batch of pitches, and Tom Kalinske remembered having seen it before. He gave the go-ahead, and Morawiec got to work on his baby. He was given only a few recommendations from upstairs, including changing the name of the main character from “Joe Pencil” and adding a sidekick. Thus, Pencil was transformed from a weak, geeky-looking nobody into hip grunge rocker Sketch Turner whose sidekick was a rat named Roadkill. It took some time for Morawiec to organize his team, but Roger Hector had complete confidence in the project and let him do what was needed.

It was at this time that Sega began to begin to work on the next generation of its hardware, with the American branch getting the 32X add-on ready for the ’94 holidays and the Japanese working on the Saturn. Naka and his team returned to Japan, leaving STI with two more Sonic sequels and a mostly American staff. No new games had been completed by this group since Sonic Spinball so the pressure was on to pick up the slack. Comix Zone was quietly released at the beginning of 1995, but it was quickly eaten up by the hype being generated by Sony’s PlayStation and even Sega’s own Saturn. Dismal sales relegated what was an excellent game to the bargain bin, and it was clear that the Genesis era was finally coming to an end. Even so, STI still had a few titles in the pipeline before moving on to more powerful hardware.

The Struggle to Adapt

With the departure of the Japanese group and the shift in hardware priorities within Sega, the staff at STI began to notice a change in the atmosphere they had come to love, but it wasn’t due to the change in its leadership. Sega as a company had begun to experience unprecedented growth after the runaway success that was Sonic The Hedgehog, and it was increasingly aware of its new market position. After Sonic 2 turned out to be such a massive hit, the Institute was transferred from Palo Alto to Redwood Shores and continued to work on Genesis titles until the console’s successor was ready. Naka’s team completed both Sonic 3 and Sonic & Knuckles back-to-back before it left, the latter of which received a massive launch party by Sega. The House of Sonic teamed up with the Hard Rock Cafe and MTV to push the game, and among the promotions was a Sonic-themed balloon in the 1993 Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade, which was the largest balloon ever made at the time and the first video game character to ever be featured. Sega flew Sonic Team in firsthand, hoping to motivate it and to ensure that Sonic’s last 16-bit sequel would be finished on time. The trip seemed to do the trick, as Sonic & Knuckles shipped on schedule. Sadly, the iconic balloon wasn’t as fortunate. During the parade, it slammed into a lamp post at West 58th Street and Broadway and deflated, knocking a light fixture onto Suffolk County police captain Joe Kistinger. He broke his shoulder bone and missed more than a month of work. Thankfully, Sonic returned to the parade in later years and remained the only video game character until Pikachu debuted in 1999.

Perhaps the most interesting part of promoting Sonic & Knuckles was how everything culminated. On a chilly October afternoon in 1994, a contest was held on the prison island of Alcatraz in San Francisco, where the best twenty-five players out of a hundred thousand entrants competed for a $25,000 prize. During the broadcast, MTV went to STI offices for look at how Sonic & Knuckles was made. For the duration of a half hour, viewers were taken on an exclusive behind-the-scenes tour of Sega Technical Institute and were treated to short conversations with many of the different staff members. It was a great chance to see how things worked, with the only downside being the lack of interviews with the Japanese developers. At the show’s end, the Rock the Rock special shifted focus back to Alcatraz and pitted the two gaming finalists against each other in a blood-racing dash to acquire the most rings. Aside from making one lucky kid a lot richer, the special also contributed to the massive sales of Sonic & Knuckles.

The success of this innovative sequel was a sweet one for the Institute, as the game was plagued by problems throughout its development. There were severe challenges inherent in creating the unique lock-on technology that allowed it to be used with past Sonic titles, and the team struggled to get the game finished in time for the MTV special. Though things sometimes looked bleak for the hedgehog’s final 16-bit outing, everything thankfully worked out in the end. Hector himself was quite relieved at its success. “There were many times I thought we were not going to make it, but it all came together at the last possible second, and it was extremely successful.” Sonic & Knuckles exploded onto shelves in October of 1994, exactly one month before the Saturn went on sale in Japan.

The success of this innovative sequel was a sweet one for the Institute, as the game was plagued by problems throughout its development. There were severe challenges inherent in creating the unique lock-on technology that allowed it to be used with past Sonic titles, and the team struggled to get the game finished in time for the MTV special. Though things sometimes looked bleak for the hedgehog’s final 16-bit outing, everything thankfully worked out in the end. Hector himself was quite relieved at its success. “There were many times I thought we were not going to make it, but it all came together at the last possible second, and it was extremely successful.” Sonic & Knuckles exploded onto shelves in October of 1994, exactly one month before the Saturn went on sale in Japan.

Meanwhile, the Americans finished up The Ooze, a wonderfully fresh game about a scientist who’s bathed in his own toxic chemical by his evil colleagues when he discovers that they intend to use it for evil. Instead of dying, he’s transformed into a slimy, living liquid. Starting as an algorithm in 1994, it wasn’t actually used until a team was finally available almost a year later. Development proceeded normally until Sega’s marketing department decided they wanted to bundle it with the Nomad, a portable Genesis. Nothing was ever successfully coordinated, and the Nomad debuted in America sans the pack-in. The Ooze, on the other hand, was eventually released too late in the Genesis’ life cycle to get the attention it deserved.

With Sega’s shift to the 32X and the Saturn, The Ooze was left with virtually no marketing, and it sadly went as unnoticed as Comix Zone had. This, along with some horrible box art, left the few gamers that actually inquired about it wondering just what the heck the game was about. The commercial failure of The Ooze is a shame, as lead programmer David Sanner had managed to successfully translate the difficult ooze algorithm into 3D, which would have opened the door for a sequel on the Saturn.

The numerous delays of both Comix Zone and The Ooze caused Sega Technical Institute to release its final two products at a time when all attention had been shifted away from the Genesis. Furthermore, by taking so long to bring the games to retail, vital development time for the newer consoles had been lost, causing the group to be tardy in its entry to the next generation. As a result, the only STI game to be released for the Saturn was Die Hard Arcade, a collaboration between the Institute and Sega’s AM1 team (later known as Wow Entertainment of House of the Dead fame). Sega of Japan’s coin-op division had over produced its Titan hardware, and since it already possessed the Die Hard license, the decision was made to create a game around 20th Century Fox’s famous movie. A core group of designers, artists, and programmers were sent from Japan to STI, which in turn provided the environment facility and additional staff for art (Institute artists like Betty Cunningham did texture work on both the arcade and Saturn versions), animation, and music. Die Hard Arcade was sold as both a dedicated cabinet and as a kit, and it went on to be Sega’s most successful U.S.-produced arcade game up to that point. The coin-op division sold off all of its excess inventory, and both branches of the company were pleased with the results of the union of team members.

In spite of this success, the future did not bode well for Sega Technical Institute. With its late entry into the 32-bit arena, along with its inexperience with the Saturn hardware and the overall difficulty in programming for it, the group found itself losing ground. The sudden departure of Tom Kalinske and most of the senior U.S. staff in 1995 brought in Bernie Stolar, the former president of rival Sony. This major upheaval in management signaled the end for the Institute, and it was quietly disbanded in 1996. Roger Hector solemnly remembers the end. “When it became obvious that Sony was taking the lead, Sega’s corporate personality changed. It became very political, with lots of finger-pointing around the company. Sega tried to get a handle on the situation, but they made a lot of mistakes, and ultimately STI was swallowed up in the corporate turmoil.”

Reportedly, STI wasn’t essentially disbanded, but instead refocused. Former Institute producer Mike Wallis summed up its fate thusly: “After Sega of America’s product development was spun off to become SegaSoft, Sega still wanted an internal PD group to develop products. STI, with its recent expanded focus of localizing Sega of Japan’s titles and of managing external development teams, was the logical choice. It was re-structured, reporting to SOA management instead of SOJ management, and expanded.” Essentially, the group was given a new name and a new mission, responding to the domestic needs of a smaller, more streamlined Sega of America.

Hidden Legacy

With the demise of Sega Technical Institute, several unreleased projects were shelved, never to be seen by the gaming public. On the Genesis, only two have come to light so far. One was a mysterious title known as Jester, an adventure featuring a clay character that was able to survive even the most deadly attacks and which was reportedly almost complete. The other was an action/platformer called Spinny & Spike. According to Steve Woita, the latter played much in the same vein as Treasure’s Alien Soldier, in that it consisted solely of boss battles. Originally conceived by Woita, Jason Plumb (both of whom programmed, designed, and practically produced the game themselves), and artist Tom Payne, Spinny & Spike had been pitched to upper management at about the same time as Comix Zone. It was given the green light by Tom Kalinske himself and became a pet project of Woita and Plumb and was on well on its way, with the trio each focusing on a specific level.

Unfortunately, Spinny & Spike was put on hold while in development when its three-man team was reassigned to help out on Sonic Spinball, a game that was desperately needed for the competitive holiday season. Woita and his group were transferred off site to devote all their energy to finishing Sonic Spinball, and unbeknownst to them, Sega brought in a new producer and a lead artist to continue work on Spinny & Spike. The new hires had a different plan of what the game would look like and began making changes that were not in the original game design. When Woita and Plumb returned to STI after Sonic Spinball was done, they found these new people (including newly hired graphic artist Chris Senn) working on their game, which was totally unacceptable to them. Tired from working on Sonic Spinball and not eager to cause a stir, Woita and Plumb instead opted to leave Sega when the opportunity arose to join Ocean of America. Woita recalls, “at that time that I was frustrated with this new look that apparently I was having less control over, I got a call from a headhunter that offered both Jason and me a great deal of money to work over at Ocean of America. So at the peak of our frustration, we just basically resigned from Sega.”

John Duggan, the art director who had joined the project before it was put on hold in favor of Sonic Spinball, was now tasked with saving it, but it was determined that things wouldn’t be able to continue without the original team. “We attempted to resurrect Spinny & Spike, but at this point Jason and Steve left.” Duggan commented to Sega-16, “Their code was determined to be too idiosyncratic and would have required starting from scratch, which was deemed to costly by this point.” Having originally ordered that embattled game be revamped in Woita and Plumb’s absence, Sega finally decided to outright cancel it. In all, about two levels were completed.

John Duggan, the art director who had joined the project before it was put on hold in favor of Sonic Spinball, was now tasked with saving it, but it was determined that things wouldn’t be able to continue without the original team. “We attempted to resurrect Spinny & Spike, but at this point Jason and Steve left.” Duggan commented to Sega-16, “Their code was determined to be too idiosyncratic and would have required starting from scratch, which was deemed to costly by this point.” Having originally ordered that embattled game be revamped in Woita and Plumb’s absence, Sega finally decided to outright cancel it. In all, about two levels were completed.

Other titles suffered setbacks as well once the Institute was restructured. Comix Zone was supposed to have received a sequel, but it too died a quick death. After the demise of STI, Peter Morawiec left for Burbank with fellow programmer Adrian Stephens to start up a small company to make games for the Genesis. When Hector and Shinobu Toyoda convinced them to stay on, the pair set up an office to work on a Sonic game. While there, Morawiec began concept work on a 3D sequel to Comix Zone, but dropped it when Naka killed the Sonic project. He and Stephens then left Sega to form Luxoflux.

Perhaps the most well-known unreleased game to come from STI was the famous Sonic Xtreme. Originally conceived on the Genesis (not to be confused with the Sonic-16 demo we debuted in our interview with Peter Morawiec), it was eventually transferred to the 32X and then to the Saturn. After numerous delays, the acquisition and then loss of development tools made for Nights: Into Dreams (another Sonic Team game), numerous switches in game engines, and the slow bleeding of team members, Sonic Xtreme was unceremoniously put down in 1997, signaling the end of the one real chance Sonic had to join the 32-bit generation.

Though only two games actually bore STI’s logo (Comix Zone and The Ooze), the contribution the studio made to the Genesis cannot be emphasized enough. Be it the continued growth and success of the core Sonic games, the innovative original titles, or the unique development atmosphere that was unrivaled anywhere else at Sega, the Institute gave us some great games and produced some amazing talent. Today’s industry would do well to take a page from Sega’s book about how to make a development team feel at home, and the story of Sega Technical Institute is living proof of how too much corporate interference can kill a good thing.

Sega-16 would like to especially thank Tim Skelly, Steve Woita, John Duggan, Mike Latham, and especially Roger Hector for their assistance with this article.

Sources

- Allen, J. (2004, March) Spotlight: Sonic Xtreme. The Lost Levels.

- Battelle, J. & Johnstone B. (1993, Dec.) The Next level: Sega’s plans for world domination. Wired Magazine.

- Chan, S. (2005, Nov. 27). Site of balloon accident is known for its crosswinds. New York Times.

- Cunningham, B. 2000). Resume. Flying Goat Graphics.

- Day, A. (2007, April) Company profile: Sega Technical Institute. Retro Gamer Magazine.

- Horowitz, K. (2005, Feb. 15). Interview: Roger Hector. Sega-16.

- Horowitz, K. (2005, Dec. 14). Interview: Steve Woita. Sega-16.

- Horowitz, K. (2006, Dec. 5). Interview: Mark Cerny. Sega-16.

- Horowitz, K. (2006, Dec. 15). Interview: Stieg Hedlund. Sega-16.

- Horowitz, K. (2007, April 3). Interview: Chris Senn. Sega-16.

- Horowitz, K. (2007, April 20). Interview: Peter Morawiec. Sega-16.

- Horowitz, K. (2007, June 19). Interview. Mike Wallis. Sega-16.

- IceKnight. Interview with Craig Stitt. Shadowsoft Games. January 23, 2001.

Pingback: Sega Saturn – Did You Know Gaming? Feat. Greg – Viral Pie

Pingback: In-Depth: Time Constraints In Sonic Games | TSSZ News

Pingback: #7FaveGames: Sonic the Hedgehog 2 | Unnecessary Writing

Pingback: Happy Holidays, Die Hard Arcade style | World 1-1