Did you know that Philip Morris sued Sega in 1991 over appearances of a reasonable facsimile of Malboro’s logo in the arcade game Super Monaco GP?

The ’90s Were a Dangerous Time for Hedonistic Cartoon Mascots

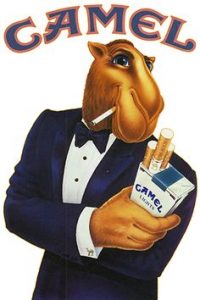

During that time period, tobacco companies were getting heat in the United States for marketing cigarettes to minors through advertisements and endorsement deals. There was a widely publicized study from late 1991 published in the Journal of the American Medical Association that seemed to really get the nation’s attention. Inside, it was found that young children from the age of six could correctly respond that Joe Camel was associated with cigarettes as well as they could respond that the Disney Channel logo was associated with Mickey Mouse.

During that time period, tobacco companies were getting heat in the United States for marketing cigarettes to minors through advertisements and endorsement deals. There was a widely publicized study from late 1991 published in the Journal of the American Medical Association that seemed to really get the nation’s attention. Inside, it was found that young children from the age of six could correctly respond that Joe Camel was associated with cigarettes as well as they could respond that the Disney Channel logo was associated with Mickey Mouse.

That was at the peak of the tobacco industry’s public relations crisis that began just a few years prior. More and more Americans finally started dealing with the fact that cigarettes were harmful during the time period. Many feared that children and young adults would get hooked at an early age and suffer from smoking-related illnesses in later life.

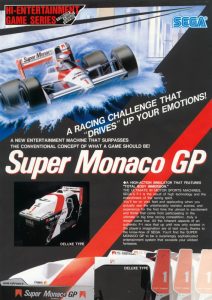

It comes as no surprise that Malboro owners Philip Morris were on edge when it came to protecting their brand’s image in the public eye. Any perceived marketing to children or young adults would be met with public backlash and potential scrutiny from lawmakers. One such unlikely place was in Sega’s own Super Monaco GP arcade game.

Why Did Philip Morris Sue Sega?

Super Monaco GP wasn’t the only Sega game with mention of the brand, either. Hang-On featured ads for “Marbor,” an obvious parody of the brand. One of the bikes on the arcade flyer is even in Marlboro colors. In Super Monaco GP, the usage is egregious, even if the it’s intentionally misspelled as “Malbobo.” In the original, unaltered version of the game, almost exact replicas of Marlboro logos with the misspelling appear on cars, billboards, banners, and signs in the crowd. The ads are even displayed in place of windows on some buildings. There’s a fine line between parody and infringement. It’s obvious some of the developers zoomed past it at top speed.

In December 1989, Dr. John W. Richards of the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta wrote a formal complaint to the Federal Trade Commission about the game. “Super Monaco GP is essentially one big Marlboro ad. A child playing Super Monaco GP is exposed to literally hundreds of Marlboro ads during the game, if he’s good. If he’s not good and doesn’t reach ‘extended play,’ then he’ll see only 50 or so Marlboro ads.”

It’s unclear how the ads featuring the “Malbobo” logo ended up in the games exactly. There was no official partnership between the companies, so Morris did not pay for them to be included. David Rosen, co-founder and then co-chairmen of Sega’s board told the Associated Press in 1990 that it was “simply a game designer’s innocent attempt to mimic real-life locations. There is absolutely no form of paid or intentional advertising displayed in any of Sega’s arcade or consumer video games.” It is very possible that the creators of the game included them to emulate a real race track, which would often have such banner advertisements. Television viewers would see the banners for cigarettes, alcohol, and other products as they watched the race take place at home.

Steven Weiss, manager of media relations for Philip Morris in New York, said the company found out about the use of its product names and logos around the time of Richards’ FTC complaint. “Sega has not asked permission to use our logo and, moreover, we would not grant such permission to use any of our cigarette logos in any video game, especially those played by minors,” he told the AP in 1990. “All our cigarette advertising and promotions are directed at informed adult smokers only.” Weiss said that Philip Morris wrote to Sega on November 20, 1989; formally requesting Sega to recall the games so that the unauthorized logos would not be available for children to play or see. The letter was sent seven days after Rep. Thomas Luken (D-Ohio), informed the company he was going to hold hearings on the video advertising. Sega told the Philip Morris and the press that it was working on removing the logos, eventually signing an agreement with Morris that it was doing so.

Steven Weiss, manager of media relations for Philip Morris in New York, said the company found out about the use of its product names and logos around the time of Richards’ FTC complaint. “Sega has not asked permission to use our logo and, moreover, we would not grant such permission to use any of our cigarette logos in any video game, especially those played by minors,” he told the AP in 1990. “All our cigarette advertising and promotions are directed at informed adult smokers only.” Weiss said that Philip Morris wrote to Sega on November 20, 1989; formally requesting Sega to recall the games so that the unauthorized logos would not be available for children to play or see. The letter was sent seven days after Rep. Thomas Luken (D-Ohio), informed the company he was going to hold hearings on the video advertising. Sega told the Philip Morris and the press that it was working on removing the logos, eventually signing an agreement with Morris that it was doing so.

Phillip Morris Files Trademark Infringement Lawsuit

Not pleased with Sega’s efforts to remove the logos from the arcade games on the market, Phillip Morris filed a trademark infringement lawsuit against the company on February 21st, 1991. The suit singled out the continued usage of the brand’s logos in Super Monaco GP after Sega signed a formal agreement to stop doing so the year prior.

Morris sought an order directing Sega to recall all of the Super Monaco GP games that used their logo. In addition, they demanded that Sega turn over all labels, signs, prints, packages, wrappers, receptacles and advertisements in its possession that bear the logo to Morris, so that they may be destroyed. They also sought an unreleased amount of damages. Steven Parris, a representative for Morris at the time, released a statement saying that his company felt that “the failure of Sega Enterprises to comply with the letter and spirit of the agreement is completely unsatisfactory.”

The Outcome of the Suit

On May 7th, 1992, after months of negotiation over the fine details, it was announced that Philip Morris and Sega had reached a settlement agreement. Sega would run three months of full-page colored ads in trade industry magazines Playmeter and Replay offering Super Monaco GP owners conversion kits and a payment of $200 if they completed the process and returned the original computer chips. The conversion kits contained decals, computer chips and the instructions necessary to complete the process. John R. Nelson, then Senior Vice President for Corporate Affairs at Philip Morris, said that “this settlement is important to Philip Morris because it effectively eliminates our Marlboro brand logos from a video arcade game used by children.”

On May 7th, 1992, after months of negotiation over the fine details, it was announced that Philip Morris and Sega had reached a settlement agreement. Sega would run three months of full-page colored ads in trade industry magazines Playmeter and Replay offering Super Monaco GP owners conversion kits and a payment of $200 if they completed the process and returned the original computer chips. The conversion kits contained decals, computer chips and the instructions necessary to complete the process. John R. Nelson, then Senior Vice President for Corporate Affairs at Philip Morris, said that “this settlement is important to Philip Morris because it effectively eliminates our Marlboro brand logos from a video arcade game used by children.”

However, some critics felt the settlement didn’t go far enough and others believed the whole event was simply a publicity stunt by Philip Morris to garner good press. “It’s a hoax. It’s one more of Philip Morris’s cruel hoaxes,” Dr. Richards told the Associated Press in May 1991 after the settlement announcement. At the time, Richards was the President of Doctors Ought to Care, an anti-smoking group. He made several public statements during the time period about the company.

Although Morris’ legal counsel argued for Sega to log all of the completed conversions of the game, no official number for the amount of machine owners who took Sega up on the offer was ever released.

Do you think this was an elaborate hoax on Philip Morris’ part to clean up its public image? Let us know in a comment below!

Pingback: Arcade Games Facts – Did You Know Gaming? extra ft. Greg – Gaming – video world

Pingback: Arcade Games Facts - Did You Know Gaming? extra ft. Greg — Gaming Cannon

Pingback: Best Of 2019: Why You’ll Never Get To Play Your Favourite Retro Game On Switch – UpMyTech

Pingback: Best Of 2019: Why You'll Never Get To Play Your Favourite Retro Game On Switch - Games Generator

Pingback: Why You’ll Never Get To Play Your Favourite Retro Game On Switch – Feature – Capcom

Pingback: Feature: Why You’ll Never Get To Play Your Favourite Retro Game On Switch – Teea Games