Sega’s 1988 release of the Mega Drive in Japan marked a new beginning for the company. After its previous console attempts, the SG-1000 and Master System, both failed to catch on, the decision was made to move ahead of the competition’s technology. It was thought that by offering consumers a product that was more powerful than Nintendo’s dominating and aging NES, Sega could chip away some market share and establish itself as a legitimate market contender.

Sega’s 1988 release of the Mega Drive in Japan marked a new beginning for the company. After its previous console attempts, the SG-1000 and Master System, both failed to catch on, the decision was made to move ahead of the competition’s technology. It was thought that by offering consumers a product that was more powerful than Nintendo’s dominating and aging NES, Sega could chip away some market share and establish itself as a legitimate market contender.

Sega knew that consoles cannot prosper on flashy visuals alone, and that it would need a solid offering of varied titles to sway gamers from Nintendo’s thrall. Along with a slew of arcade conversions, Sega reached into its 8-bit catalog and revisited its most ambitious console franchise to date, Phantasy Star. With the power of the 16-bit Mega Drive, many of the limitations that had restricted the first game’s development were lifted, and the development team could explore the Algol star system (spelled “Algo” in the English version) much more closely to the way it had originally intended. The result was one of the most involved and challenging RPGs of the era, one so memorable that it is still discussed and regarded today.

But the creation of Phantasy Star II was not easy, and what Sega fans received upon the game’s debut in March 1989 (a year later for U.S. Genesis owners and almost two for European fans) was unlike anything they expected. What Sega unleashed that year would solidify Phantasy Star as a fan-favorite series and bring console RPGs to a whole new level.

A Return to Algol

When work began on the next Phantasy Star game, it wasn’t for the Mega Drive but for the Master System. Many of the same people responsible for the original hit returned, including Designers Rieko Kodama and Naoto Oshima, Character Designer Kotaro Hayashida, and Programmer Yuji Naka. Together, they planned on fleshing out the fantastic world of Algo in much greater detail. Phantasy Star had wowed Master System owners with its clever mix of traditional fantasy elements with sleek and eye-catching sci-fi designs, and the sequel would place more emphasis on this mixture, giving the sci-fi aspect of the sequel more of its own identity. Examples of this were that magic was renamed “technique,” and dead characters are now cloned in a lab instead of revived at a church. Weapons and armor were now “gear” and “suits” of carbon and titanium. The fantasy details were still present, but they were more subdued in favor of Algol’s futuristic side.

The expansion of Phantasy Star’s world soon took an unexpected turn. Early on in development, Sega decided to move the project to its new 16-bit machine, forcing the game’s writer and director, Akinori Nishiyama, to make some major changes to its overall design. The shift to newer hardware also came without any extension to the development window, giving the group a mere six months to complete the game. The schedule was, as Hayashida described it, “oppressive.” The challenges of such a short window and learning the new hardware meant that there had to be several changes made to the development plan.

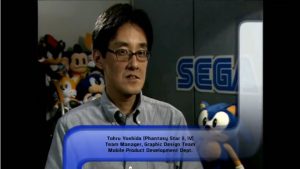

The urgency was instantly apparent to Tohru Yoshida, who had just been hired at Sega as a graphic designer. Phantasy Star II was his first project, and he took charge of monster designs and the animations. These areas were much more complex than those of the first Phantasy Star, were almost more work than Yoshida could keep up with. He came up with the design of the game’s principal antagonist, Mother Brain, through what he called a combination of the maternal image and computers. The all-powerful machine that maintains the climate of the planet Mota green and lush, it schemes and plots throughout the game to destroy Rolf and his companions. Yoshida crafted Mother Brain to be god-like but also manipulated by the sinister Dark Force.

Mother Brain and the evil behind her were as much social commentary as they were video game plot devices. Phantasy Star II tackles the issue of our dependency on technology and the havoc it can wreak. Mother Brain controlled and provided the inhabitants of Algol with everything they needed, and no one questioned her restrictions, such as the prohibition of space travel or making the oceans off limits. Humans were the invasive species that had caused Algol’s problems, and they had become too complacent and weak to take action when Mother Brain lost control. Players are forced to work within that reality. One must keep in mind that Phantasy Star II was released in 1989, and such themes were not commonplace for console video games. The concept of a utopia that was too perfect and manipulated by a cosmic evil was still fresh and immersive.

Yoshida immediately found himself hindered by the small color palette of the Genesis but managed to work within those limitations. He also struggled with the hardware while working on the game’s backgrounds. “I was using pixel graphics at the time and constantly thinking about the best ways to depict three-dimensional landscapes within the constraints of the system,” he detailed in the Mega Drive/Genesis Collected Works. “I was obsessed with using parallax scrolling in Phantasy Star II, but this made it hard for players to see the action, which made me realize that it was a mistake. After all, it is vital for players to easily understand what is happening on the screen.”

The effect of the reduced development schedule was most notably felt in the game’s storyline. Though there was a connection with the characters from the first game, the ties were more implicit. For example, the hero of Phantasy Star II, Rolf, was a descendent of Alis. Additionally, the space pirate Tyler was related to Odin (called “Tyron” in the Japanese version). The cats encountered in Skure on the planet Dezo were all direct descendants of Myau. According to Yoshida, Myau’s kittens became pets of the inhabitants of the Skure station. When those people died, only the cats remained. Yoshida and the others had wanted to make one of the cats a playable character, but they couldn’t make the battle scene graphics work. It is never made clear in the game that the cats are directly related to Myau, but any Phantasy Star fan was quick to see the relation. There was no way that the cats’ graphics could be a mere coincidence. Until Yoshida’s explanation in 1993, however, most people thought it to be no more than a mere homage to the original game.

Despite the difficult schedule and learning curve of new console tech, the development group worked well together. Three different people were responsible for Phantasy Star II’s graphics, and they coordinated regularly to ensure that there was a consistent flow to the graphics. All three designers: Kodama, Yoshida, and Mechanical Designer Yasushi Yamaguchi; had a fluid work dynamic. They were helped greatly by the fact that every member of their team could work on graphic design. Instead of dividing them into character and background graphic designers, the Phantasy Star II team organized them more or less into main and secondary graphics roles.

Kodama’s initial vision for Phantasy Star’s sequel had a slightly different tone than its predecessor. The original game was renowned for its strong female lead character, Alis, who assembled a team of heroes to avenge her brother’s death and rid the Algol system of the evil Dark Force. For the next installment, Kodama had originally planned to make Lutz, the magic-using Esper of the team, the hero. “In the earliest drafts for Phantasy Star II,” she explained in a 1993 interview for the Japanese World of Phantasy Star book, “the main character is Lutz, and it opens with him awakening from cryosleep. In the 1000 years since Phantasy Star, his abilities have changed. He’s more of a warrior now, and he sets out to wander the world. There was also a part where he warps back in time and has to save Alis at the time of her birth. In the end he defeats his enemies and vanishes again.”

Cementing long-term plans for Lutz seems to have been a problem for Kodama and her team, as the character was ultimately given a secondary role in favor of Rolf. Yoshida revealed in 1993 that the decision to change main characters actually came from Yuji Naka. “In the original character design for Lutz from Phantasy Star, his personality was very weak and undefined, so Yuji thought Lutz would be a bland protagonist for Phantasy Star II if we just used him as-is.” Though he would now take a back seat to Rolf, Lutz would continue to be a major part of the overarching storyline. He would once more be a factor in Algol’s fate in the series final in 1994, but his role in Phantasy Star II was significantly diminished.

Changing protagonists meant that the team would have to make major alterations to the game’s plot, and this wouldn’t be the first time the team had done so. The first draft, which had Lutz as the hero going back in time to aid Alis in her battle against Lassic, had been problematic. The writer of the first Phantasy Star, Chieko Aoki, wasn’t fond of re-writing the series’ history and erasing past events. Aoki’s revision didn’t radically alter the story of Mother Brain’s descent into madness, but there were several major differences. In the second draft, Lutz was to awaken with the mission of investigating Mother Brain, finding himself embroiled in crisis on Mota when a plague of plants affects the planet’s irrigation and caused widespread famine. His efforts to destroy the plants by flooding the planet led to the native Motabians to be accused of terrorism and hunted by robots. This line was altered for the third and final released version, where Rolf and his group had to open the dams to prevent Mota from flooding, all the while hunted as traitors. Other story elements, such as the planet Dezo having a much larger role in events, were omitted entirely.

Don’t Get too Attached to Nei

Character development was an important element of Phantasy Star II. The game has the distinction of incorporating one especially tragic plot twist that was a console RPG first. Gamers love to comment about the death of Aerith Gainsborough at the hands of the villainous Sephiroth in Square’s Playstation classic Final Fantasy VII, but Phantasy Star II beat it by almost a decade. Perhaps it was not the first game to kill off a main character, but it marked the first instance of such an event occurring in a console RPG in such dramatic fashion, particularly one as high profile as the Phantasy Star series. Nei’s death at the hand of her numan counterpart Neifirst (the game’s first boss battle) came at a major turning point in the story. The party explores the Mota Biosystems Lab to discover the reason for recent biomonster outbreak. At the end of their investigation into the lab, they find another numan called Neifirst, who reveals that she is responsible for the outbreak. Furthermore, the party discovers that Neifirst and Nei are two halves of the same being, one good and one evil. After some dialogue, the two do battle, and Nei is killed. The combat is a particularly sad event, and one feels a looming sense of dread during the entire affair, as though it is preordained that the battle can have no positive outcome. The players seek revenge and fight Neifirst, which is much harder now that the party is missing a member.

Character development was an important element of Phantasy Star II. The game has the distinction of incorporating one especially tragic plot twist that was a console RPG first. Gamers love to comment about the death of Aerith Gainsborough at the hands of the villainous Sephiroth in Square’s Playstation classic Final Fantasy VII, but Phantasy Star II beat it by almost a decade. Perhaps it was not the first game to kill off a main character, but it marked the first instance of such an event occurring in a console RPG in such dramatic fashion, particularly one as high profile as the Phantasy Star series. Nei’s death at the hand of her numan counterpart Neifirst (the game’s first boss battle) came at a major turning point in the story. The party explores the Mota Biosystems Lab to discover the reason for recent biomonster outbreak. At the end of their investigation into the lab, they find another numan called Neifirst, who reveals that she is responsible for the outbreak. Furthermore, the party discovers that Neifirst and Nei are two halves of the same being, one good and one evil. After some dialogue, the two do battle, and Nei is killed. The combat is a particularly sad event, and one feels a looming sense of dread during the entire affair, as though it is preordained that the battle can have no positive outcome. The players seek revenge and fight Neifirst, which is much harder now that the party is missing a member.

Square was able to present a much more engaging death for Aerith, thanks to the multimedia capabilities of the CD-ROM format, but Nei’s death was just as shocking for Sega fans almost a decade prior. It was inconceivable to many that such a prominent character would die in a game, especially one as endearing as Nei. She was young, optimistic, and courageous – not the type of character one would expect the developers to kill; however, her death, though tragic, was pivotal for the story, as it gave Rolf and his companions a greater sense of purpose and made their quarrel with Motherbrain a personal affair.

New Console, New Direction

One of the most innovative and beloved aspects of the original Phantasy Star was its 3D dungeons. Remarkably fluid and engaging, they were the creation of Sega genius Yuji Naka. Players loved (and loathed) getting lost in the multi-floor dungeons that filled the game, and there were many requests to include the 3D perspective for the sequel. Unfortunately, it was not possible to do so, given the memory constraints of the new machine. Kodama believed that to create a convincing 3D effect on the Genesis, with rotating floors and other features, would have consumed too much memory. Naka wanted to continue with 3D dungeons, but he knew that it not was possible to do them within the confines of the 6M cartridge. Another problem was that there simply wasn’t enough time. The design team had been working on the story for several months, but by the time actual art work and programming began, less than three months remained until release. Naka expressed this frustration in a 2017 interview. “For Phantasy Star II, I wanted to do the 3D dungeon as well; however, no matter how hard I tried, the capacity for the Genesis cartridge was limited, and there were only two and a half months for the development period. Therefore, not being able to squeeze out that time for making the 3D dungeon was the biggest issue. If there had been more time, I wanted to do the 3D dungeon for Phantasy Star II too.” Also, Sega was not willing to upgrade to a larger ROM size. The final version was already the largest console game ever released at the time, and it likely would not have been cost-effective for Sega to increase the cartridge size any further. As it was, several items were left on the cutting room floor, such as four monster designs that Yoshida had completed. Naka had to beg just to get the extra 2MB that were added, and he didn’t want to push his luck any further. “The monster data and the dungeon data wouldn’t fit into the 4meg cartridge at first,” he confessed, “so I begged at an executive meeting to have the cartridge upgraded to 6MB and promised them that I would make the deadline no matter what. This eventually became the reason I was able to make it within 2.5 months, and I learned the lesson to be careful on what to say in front of high ranking officers at meetings.”

Hayashida wasn’t fazed by the decision to remove the 3D dungeons, arguing that they were never the essence of what Phantasy Star truly was. Moreover, he considered them to contribute to the game’s overall difficulty. “Being able to save your game in the dungeons led to a huge problem,” he contended in the same 1993 interview as Kodama. “If you were deep in a dungeon and very close to death after a battle, you could then save your game. But in doing so, you’d always start out in that weakened state, and if you encountered an enemy you would never win, thereby getting trapped in the dungeon forever. It was especially tragic if it happened in the latter part of the game. With tears in your eyes, you’d have no choice but to start a new game.” He may have been right, as any Phantasy Star player who defeated Lassic at the end and lacked an acorn or the two technique points needed to fly back to town will remember. The game was essentially broken, and there was no other recourse but to start over.

Hayashida wasn’t fazed by the decision to remove the 3D dungeons, arguing that they were never the essence of what Phantasy Star truly was. Moreover, he considered them to contribute to the game’s overall difficulty. “Being able to save your game in the dungeons led to a huge problem,” he contended in the same 1993 interview as Kodama. “If you were deep in a dungeon and very close to death after a battle, you could then save your game. But in doing so, you’d always start out in that weakened state, and if you encountered an enemy you would never win, thereby getting trapped in the dungeon forever. It was especially tragic if it happened in the latter part of the game. With tears in your eyes, you’d have no choice but to start a new game.” He may have been right, as any Phantasy Star player who defeated Lassic at the end and lacked an acorn or the two technique points needed to fly back to town will remember. The game was essentially broken, and there was no other recourse but to start over.

An overhead view was instead used for the dungeons, and these were designed by a new Sega employee. (possibly “Gen” or “Wakasama,” based on the gameographies of the designers involved). Apparently, the young man was a bit overzealous in his efforts to impress his new bosses, and his designs were much more complex than the team had planned. Aoki wasn’t too fond of the large and difficult designs but didn’t want all the new designer’s work to be shelved, so she reluctantly decided to include them. Hayashida felt that the designs shifted the focus to the dungeons than the story and made the second half of the game unbalanced.

Likey due to the complexity of the dungeons, Sega of Japan developed a hint guide that was available upon the game’s release, and it was definitely a worthy purchase. The guide was offered to Sega of America for the U.S. release, and SOA head of marketing Al Nilsen came up with the idea of bundling it with the game itself. “I wanted it included for two reasons,” he explained in an interview for this article. “It was going to be our most expensive cart, and I wanted to give an extra value. and it might encourage people who hadn’t bought an RPG before to try Phantasy Star II, since it had a hint book in case they needed some help.” The decision turned out to be a wise one. Phantasy Star II was incredibly challenging, particularly in its second half. The addition of the hint book may have spoiled certain plot points, but it proved invaluable for navigating the dams of Motovia and for collecting the Nei weapons for the final battle. It also alerted players to the fact that Shir Gold, a character most tended to dismiss, could steal invaluable curing and revival items like Star Mist and Moon Dew from stores. Additionally, once she reached level 10, she could acquire an item called the visiphone, which let players save the game anywhere, instead of only back in town.

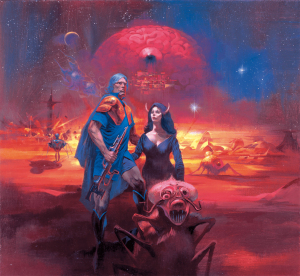

Sega of America also swapped out the beautiful Hitoshi Yoneda artwork for a piece done by an unknown artist. The Genesis cover is not a bad piece of art by any means; it’s actually quite beautiful. Lamentably, it doesn’t connect with the in-game visuals at all. Neither Rolf nor Nei look anything like their sprite renditions. They’re depicted as older and nobler. Even Mother Brain is completely different. Looming over the landscape, she is literally a brain with an eye and looks suspiciously like the Mother Brain of Nintendo’s classic Metroid.

Tokuhiko “Bo” Uwabo returned to Phantasy Star as music composer. With the Genesis, he was able to create a much more ambient score that could convey rising tensions for boss battles or even the differences between towns. For example, the shift in the emotional level was evident to players as soon as they entered the battle with Neifirst. Likewise, each dungeon had its own distinctive theme. The music for towns on Mota and Dezo, despite sharing graphical assets, helped give both of those planets their own feel. Uwabo’s score sounded crisp and clear on the Genesis, making use of effects that few other games seemed to use. Played through a stereo system, it sounded spectacular.

An Unparalleled Adventure

Phantasy Star II arrived in Japanese stores on March 21, 1989. When it was released in North America a year later, it was met with praise by the gaming press. Electronic Gaming Monthly praised it as one of the best RPGs ever made, and VideoGames & Computer Entertainment magazine awarded it “Game of the Year” for 1990. The press lauded its visuals and length, as well as its brutal difficulty. The included hint book and larger cartridge size made the game’s price as daunting as its dungeons, and Phantasy Star II arrived in stores with a $70 price tag. Still, fans and Genesis owners happily returned to Algol, and those who did took on an adventure unlike any they had played on a console before.

Phantasy Star II arrived in Japanese stores on March 21, 1989. When it was released in North America a year later, it was met with praise by the gaming press. Electronic Gaming Monthly praised it as one of the best RPGs ever made, and VideoGames & Computer Entertainment magazine awarded it “Game of the Year” for 1990. The press lauded its visuals and length, as well as its brutal difficulty. The included hint book and larger cartridge size made the game’s price as daunting as its dungeons, and Phantasy Star II arrived in stores with a $70 price tag. Still, fans and Genesis owners happily returned to Algol, and those who did took on an adventure unlike any they had played on a console before.

As fun as it was, Phantasy Star II represented something greater. Sega did more than simply release a massive game; it changed the RPG genre completely. Phantasy Star II emulated its predecessor by challenging established conventions with its sci-fi setting, character death, and serious themes. It also pushed the boundaries of what console RPGs provided by delving into the pasts and personalities of its main characters, and it built a universe that was interesting and complex. Those accomplishments have endured, as has the series’ popularity.

Fans have long commented on the ending to Phantasy Star II and whether the characters survived after defeating Mother Brain. While no one on the development team has ever given a concrete answer about what happened after the game ended, Yoshida was willing to speculate in 1993. “I’m not sure I can say we never thought about it,” he mused, “but it’s more to the point that we wanted players to be free to imagine it for themselves. But we did have some ideas as developers, so you do see some events in later games that tie back to Phantasy Star II: for instance, the statues of the eight heroes who fought for Algol in the warrior’s temple of Phantasy Star IV, or the town where people know about the legend of Alis…” The development team apparently decided against making such a connection, since the statues were not included in the final version of the game that shipped in 1994. Thus, we’re left with speculation of our own as to the fate of Rolf and his companions.

Sega’s inaugural 16-bit RPG continues to spur discussion today. Some deride its overly difficult dungeons and tendency to require players to grind for experience points, but those complaints were not uncommon of RPGs at the time. Beyond these genre tropes, there lies a story that was captivating and inspiring. It continues to be so for gamers to this day, and many yearn for Sega to revisit the Algo System for another installment.

Sources:

- “1993 Phantasy Star II Developer Interview.” GSLA. (n.d.). Web. 1 Jan. 2018.

- Lachel, Cyril. “Phantasy Star II: Were Critics into Sega’s RPG in 1990?” Defunct Games. 02 June 2014. Web. 1 Jan. 2018.

- Mimi, Arisawa. Phantasy Star VR Complementary Plan. Tiny Beep. 2017.

- “Phantasy Star 1993 Developer’s Interview.” (n.d.). Web. 9 Aug. 2017.

- Stuart, K. Interview with Tohru Yoshida: Visual Designer. Mega Drive/Genesis Collected Works. (2015). 282-283.

Pingback: O Maligno Guia de Phantasy Star II | Drive Your Mega