The following interview was originally published in May 2002 as part of Sega of Japan’s Masterpiece Album series, which featured comprehensive talks with some of Sega’s brightest Japanese arcade and console designers. It was translated by the author as research material for the Flicky section of the book The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games.

The following interview was originally published in May 2002 as part of Sega of Japan’s Masterpiece Album series, which featured comprehensive talks with some of Sega’s brightest Japanese arcade and console designers. It was translated by the author as research material for the Flicky section of the book The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games.

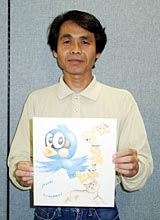

Yoshiki Kawasaki joined Sega in 1976 as part of the customer service system administrative team. He worked on the visual design of many classic ’80s arcade games like Flicky, Spatter, and Ninja Princess (Sega Ninja in the West) in the R&D Design department. Ninja Princess was Kawasaki’s final game, as he soon moved to Sega’s public relations department and then to customer service.

Sega: You’re a veteran of over 20 years here. Could you tell us about what made you join?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: I was unemployed and looking for companies near my home. I was introduced to two companies, one near Ômori station, the other near Ôtorii. I was living near Kôjiya station and commuting to Ômori would have been a pain, so I decided on the company near Ôtorii, which was Sega.

Sega: Well, that’s a simple reason. (laughs) What kind of company was Sega at that time?

Yoshiki Kawsaki: I think at that time they still mainly developed jukeboxes and pinball machines. That was before TV games were a thing; you could only find machines on the roof of department stores or snack shops. There were few arcades.

Sega: Have you played things in these locations?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: There was a dingy arcade near the old Hibiya movie theater where I played pinball and driving games. After I had joined the company, I loved Head-On. I played that game for hours. I’m getting a really intense feeling (laughs). Even when I played for a straight hour, the game didn’t end. I only stopped when I felt like it. I like simple games like that.

Sega: Did you join Sega as a designer?

Sega: Did you join Sega as a designer?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: When I joined, I was assigned to the purchasing department, but Sega had just started making home consoles and was lacking developers. It also lacked designers. Mr. [Hideki] Sato knew that I had been drawing things for a long time, so he moved me to the visual design division of the R&D department.

Sega: What was the first game you did design work on?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: The first was Golgo 13 for the SG-1000. I was placing pixels while in a daze for several nights straight (laughs ). The next game was Albegas. That was an easy one because I only made the bullets. It was a laser disc game, so there was no need to draw characters or backgrounds. I also worked on the arcade game Sindbad Mystery that ran on the Z80 board, which only had little memory for sprites. With the thought of “let’s make something more interesting,” I received the next proposal from the lead planner, a single DIN A4 page [Ed. Note: DIN refers to the page format] (laughs).

Sega: That was Flicky?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Right. The game would have you collect dots in a top-down maze. It was a really simple design document. It said things like: “since the maze can be simple lines, the characters can look simple too. You can leave the background black” (laughs).

Sega: So that means the theme of a mother bird catching her young wasn’t part of the original plan?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: A couple years earlier, the song “Densen Ondo” was really popular… the one that goes “three sparrows on the electric line…” That’s why we made the main character a sparrow that walks on power lines (laughs). Flicky is actually a sparrow. I guess it’s weird to have a sparrow move on power lines without flying? But I like the way she so heroically jumps.

Sega: So, Flicky was a sparrow all along?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: (Laughs) I always thought she was the mother bird of those baby birds… The instruction manual for the SG-1000 version does say “mother,” but that’s actually wrong (laughs). The manual was already done, so we couldn’t say she was a sparrow. But we thought, “well, she is acting alone, so it might be all right” and didn’t say anything. Flicky isn’t the mother of the birds but their friend (laughs).

Sega: So that’s how it is… The truth about Flicky comes out after 18 years.

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Well, if players think of Flicky as the mother bird, then that’s fine. I only focused on making a blue sparrow. Now that I think about it, I guess it’s reasonable that they’d think that way. Also, interpreting characters is fun.

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Well, if players think of Flicky as the mother bird, then that’s fine. I only focused on making a blue sparrow. Now that I think about it, I guess it’s reasonable that they’d think that way. Also, interpreting characters is fun.

Sega: The history of Sega has now certainly been overwritten (laughs). From now on, Flicky is a sparrow and the friend of the Chirps! Did the game’s design change after you started?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: It did. For example, I drew horizontal lines on the screen to resemble power lines. They were basically the walls of the maze, but once the character of Flicky was completed, power lines felt a bit too boring for that world. Then, I saw the apartment building across the street from the third floor of our R&D annex building. That’s when an idea came to me: Maybe the game could take place in an apartment instead of on power lines?

Sega: I see. That became the background that’s in the final game.

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Yes. That’s why you can find household items like baby bottles and cups lying around. So, because it’s a home, it’s only stuff you use in daily life (laughs). The dots you have to collect were originally really just dots. When you collected one it would disappear, but then I thought it would be interesting if the dots didn’t disappear but instead lined up. So, I made the dots line up behind Flicky. That’s when I really started fleshing things out. I asked if I could make the dots 8×8 pixels big, but in the end, I couldn’t do anything with 8×8 pixels. Then I thought: If they were little birds, I could do it… (laughs)

Sega: And that’s how mere dots turned into Chirps.

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Well, that’s how they came to fall in line behind Flicky.

Sega: That’s close to the final game.

Yoshiki Kawasaki: By the way, when I tried it out, I simply brought all the Chirps back home. Then I thought it would be more interesting if they scattered when you got hit by a cat. But even then, it was easy to simply recollect all the Chirps immediately. That’s when I decided to make some of them go in a random direction. In that way, I expanded the game with more and more ideas while keeping the difficulty level the same.

Sega: I see.

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Then I asked myself how one could differentiate between the normal Chirps and the ones that move wherever they wanted. This lead to the creation of the bad Chirps. I put sunglasses on them and called them “Bad Chirps” (laughs). [Ed. Note: “Bad” in the sense of “delinquent” or “punk.”] That way, you could easily distinguish them. Well, I say that, but the difference is actually just two or three black pixels.

Sega: In the arcade version they really look like sunglasses though.

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Yes.

Sega: But in the SG-1000 version, the bad Chirps are completely black (laughs).

Sega: But in the SG-1000 version, the bad Chirps are completely black (laughs).

Yoshiki Kawasaki: I didn’t have anything to do with the SG-1000 version, but that was due to spriting issues.

Sega: We’ve heard a lot about your troubles at that time, but how easy was it to create the pixel graphics?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: The graphical tools we had at that time were on the same level as a TV Oekaki Taburetto (graphics tablet). Whenever you wanted to draw a single pixel, it would draw three or four at once.

Sega: So, drawing the sunglasses was a pain too (laughs). By the way, how long was the development time for Flicky?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: About one year. Shortly before the playtest, we had about 100 screens done but hardly any space left. I hadn’t even done most of the backgrounds. I thought that would leave a bad impression, so I just created about four patterns for the backgrounds and differentiated the worlds with different colors. With each stage, the background would slowly change, with the final one looking like space. For coming up with this scheme that delivered good results with little work, the others called me “Sabori Kawasaki” (laughs). [Ed. Note: “Sabori” is a slacker, someone who doesn’t try hard to do something or even doesn’t do it at all. It’s often used for people skipping school or work. The nickname could thus be translated as something along the lines of “Slacker Kawasaki” or “Shortcut Kawasaki.”]

Sega: There are some images on the walls as well, like elephants and trains. Did you make those too?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Yes, I did all the background images. The design for the bonus stage is really cool, especially the see-saws! I did make the sprites and see-saws but the stage itself was the domain of the lead planner, so it already looked cool like that from the beginning.

Sega: Did you make any big changes because of the playtest?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Yes. After the playtest, we added a monster that would stick its head through the window and breathe fire, as well as a character called Choro [Iggy in the west] . I thought the game didn’t need more characters, but then a programmer pointed out that Flicky couldn’t get hurt while standing still, so we added one. By the way, Choro is a lizard, not a bug. Although I’d like to replace it.

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Because I was a slacker (laughs). He only has two movement patterns. I only made that character as a last resort.

Sega: I see (laughs). What is your favorite character?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: I like Flicky, but I also like the little Chirps toddling around.

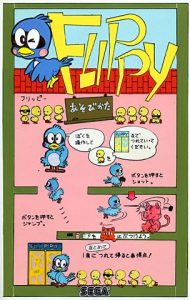

Sega: This is the game’s instruction card. Hand-drawn too!

Yoshiki Kawasaki: I finished this card in one day (laughs). At the time we didn’t have a color copier, so we always had to go to a printing company in front of JR Kamata station to get copies. Namco was using that place too.

Sega: Ah, I think something is off about the title…

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Ha ha, well spotted. If you look closely, you’ll see it says Flippy. There was a trademark issue in the U.S., so we changed it to Flicky.

Sega: Huh, I see.

Yoshiki Kawasaki: While we’re on the topic of names, an arcade in Kamata managed by Sega is also called Flicky (laughs).

Sega: That’s great (laughs). What games after Flicky have you done design work for?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: After Flicky, I worked on Champion Boxing and Ninja Princess. By the way, because the SG-1000 version of Champion Boxing was so good, it was ported to the arcades. But because it took the factory about three months to create the ROMs, I think the arcade version came out first.

Sega: And another part of history gets rewritten. Champion Boxing was ported to the arcade. Duly noted!

Yoshiki Kawasaki: I digress, but I don’t like “killing” characters. Neither my player nor enemy characters die. So, I always have to think about how to depict them “vanishing.” Flicky doesn’t die either, and even when the Ninja Princess gets cut by a shuriken or katana she doesn’t die; she just sits down and cries. Not even the enemy ninja or demon bosses die. When you beat the game, you can see them dancing with the princess on a stage.

Sega: Now that you mention it, that’s true.

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Arcades at the time had a bad image, so we brought out Flicky, a game without killing or dying. Ninja Princess and Spatter were the same. I had this attitude of “let’s make the world friendlier. Sega can make cute games!”

Sega: So, that’s where your determination lies.

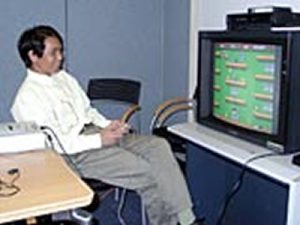

Kawasaki then played Flicky for the first time in five years. He had some trouble at first but then managed to dominate the game and get a high score of 106,350.

Sega: How was it to play the game for the first time in five years?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Difficult (laughs). The game itself is very simple. It’s annoying… even though the game is so simple it beats me. Then I get angry and pump more quarters in because I want to try again. Ha ha.

Sega: This is a question that’s always asked: If you were to remake Flicky now, what would it look like?

Yoshiki Kawasaki: Hmm… Flicky was designed as a maze-game, and gaming has evolved a lot… Fire is coming out of the windows and Flicky has to line up the Chirps who have the power to extinguish it. When there is a burglar in the room a fight occurs between the Chirps and the burglar… ah, maybe it would be cute if you had to stop a baby from crying as well? Oh, I’m getting lost in my own world. But I’ve moved away from developing games and the entire environment has changed, so I’ll leave the game-making to the young developers (smiles).

For the complete story of Flicky’s development, be sure to read The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games. The book chronicles Sega’s arcade legacy from 1966-2003 and is available in paperback and digital formats now from Amazon.

Recent Comments