When asked about the biggest rivalries in video games during the 1990s, the most common answer that comes to most people’s minds is Sega vs. Nintendo. While certainly the biggest and most memorable of the era, it was only one of several battles in which Sega was engaged. On a separate front from its back-and-forth with Nintendo for console dominance, the company was locked in a fierce competition with Namco for the best arcade racing game. As the two giants exchanged blows, gamers were the true winners, benefiting from an incredible display of creativity and innovation that, together with light gun and fighting games, made the genre one of the pillars of coin-op amusement. Classics like Ridge Racer and Daytona USA brought timeless experiences to joyful players worldwide, and they pushed both Sega and Namco to raise the bar for what could be done in racing games.

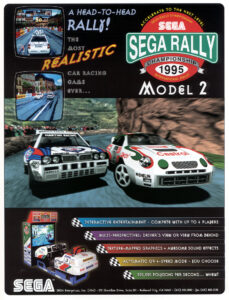

A result of that relentless pursuit for perfection was 1995’s Sega Rally Championship, a game that tore up arcades and made the Saturn shine with an amazing home port. A direct evolution of the line of Sega’s 3D arcade racing games that began with Virtua Racing in 1993, Sega Rally Championship took the sum of the creativity and experience gained from previous releases and leveraged them into something that felt instantly familiar but markedly distinct at the same time.

3D or Not 3D? There is No Question!

For the coin-op amusement business, the advent of 3D technology was literally a game changer. Thus far, 2D had dominated the designs of arcade titles, but a new day was dawning. People had anticipated such a move for years, with early 3D games like Atari’s Battlezone (1980), but the ambition of game developers still extended farther than their reach. As the 1990s arrived, technology finally began to catch up. It was impossible to see where the 3D and computer graphics (CG) would take the industry, so all the creative minds of game factories like Sega could do was research and experiment to find their muse.

Such innovation did not come cheap. At the time, it was still quite expensive to outsource imaging to an external computer graphics company, so Sega sought to develop its own talent in-house. There were few people at the time with such expertise, and the task to recruit them fell to Tetsuya Mizuguchi, who would go on to make such Dreamcast classics as Rez and Space Channel 5. While still in college, Mizuguchi applied for a job at the legendary firm after playing an R-360 cabinet, which encased players in a giant cabinet that gyrated them a full 360 degree on the x and z axes. He enjoyed Sega’s other taikan, or “body sensation,” games and wanted to be part of the company that made such amazing products. Mizuguchi saw a daring and decisiveness in Sega to go in any creative direction, and that philosophy prompted him to storm into the company’s Hanada headquarters and ask for a job. He was told to contact human resources where he was introduced to Sega R&D head Hisashi Suzuki. When Suzuki asked him why he came to Sega, Mizuguchi gave a startling reply. “It’s not games that I want to make,” he said. “What I want to make is not like video games that already exist. I want to make something more amazing, like the future of entertainment.”

Mizuguchi showed Suzuki a treatment he was working on, 40 pages of technology, art, and entertainment that included a “virtual environment display system,” or VR device. It was supposed to be a simulation of NASA’s Ames Research Center Mars rover, and Mizuguchi pitched it by confidently claiming that 3D CG and VR would one day become part of video game design. This was 1989, mind you, a time when such concepts were still not part of the common vernacular, and certainly not on the minds of most people in the video game industry.

His proposal worked, and Suzuki hired him, even granting him the concession of skipping the hiring process up to orientation day so he could travel and experience things that would help his work at Sega. Mizuguchi used the time to take a trip to North America in March 1990, traveling the country for an entire month. He journeyed from San Francisco to Chicago, then to Canada, New York, and finally Florida before returning to California through Mexico. He even survived someone breaking into his car and stealing all his belongings in New York. It was an exhausting trip, but his wanderings through the different environments and landscapes would serve him well for his first video game project…

… which was not the first thing he worked on upon returning to Sega. Rather, Mizuguchi started out as an assistant to Suzuki. The position did give him more opportunities to travel, and when he learned that his boss would be attending the 1st Virtual Reality International Conference in Austin, Texas, he begged to go, even paying for the trip out of his own pocket. The conference turned out to be kind of a bust, with only about 20 or so people in attendance. “In the middle of the hotel lobby, there was a demonstration with all these wires and a person wearing a VR headset,” Mizuguchi lamented. “The CG was flickering, too. It was like, ‘…Eh, it’s just this?'”

Under such disenchanting circumstances, it may not have been apparent, but Mizuguchi had gotten in on the ground floor of Sega’s conversion to 3D. Virtua Racing (1992) and Virtua Fighter (1993) were seismic shifts within the company, fueled by the powerful new Model 1 arcade board. Mizuguchi was excited by its potential and secured assignments to collaborate with Sega’s AM5 team, responsible for creating large-scale attractions for indoor amusement centers and theme parks. His first project was the AS-1 Simulator. That machine would serve as the catalyst for Sega’s efforts to build its internal, high-end 3D studio, but Mizuguchi was the among the few willing to accept the challenge of putting it together. He gathered other designers and held workshops to consider how to make games that were more fun. They compared video games to film and discussed how the media could be as emotionally moving as cinema. Mizuguchi figured that if he could get hold of the technology needed to make CG images, he could recruit others to join him to create those realistic game structures. “So, I created a new team and requested approval to buy a Silicon Graphics [workstation] which cost about one million yen ($10k) back then, and about three units of Softimage, which cost about six million yen ($60k) per unit, and video editing equipment. It was a total of about 100 million yen ($1,000,000).” His new team, called the “Emotion Design Lab,” sought to research, propose, and realize new ways of having fun.

The Right Men for the Job

The arrival of Sega’s new Model 2 arcade board gave Mizuguchi the opportunity to put to use what he had learned, and he was eager to move into the video game space. The architecture resulted from a year-long venture between Sega and GE Aerospace and could push up to 500,000 polygons per-second, a huge boost from the 180,000 per-second of the Model 1. It also added advanced features like texture filtering (used to determine what pixel color will be on 3D surfaces), texture anti-aliasing (to reduce jagged edges, flickering, and shimmering that occur when textures are viewed at an angle or from a distance), and trilinear filtering (to smooth changes between different texture resolutions, which are called mipmaps). It was a giant step up technologically, and it was a clear statement by Sega that it wasn’t about to back down against the competition.

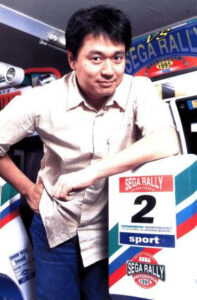

With such power, Mizuguchi felt that he could make an immersive and realistic title that would blow gamers away. When Sega decided to start a new team for Model 2 development, he leapt at the chance. Mizuguchi was then asked what position he would take in the new unit. “I answered, ‘I’ll be a producer,’ which was met with, ‘Producer… what do they do?'” He later commented that many within management often didn’t know, as such positions weren’t commonly identified. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, game companies prohibited development teams from using their real names in the credits of their products to avoid talent poaching from rival companies. By the mid-1990s, this practice was no longer acceptable to many creators, and people began to make noise within their workplaces to be credited for their specific talents. According to Mizuguchi, the transition of video games into 3D accelerated this cause. 3D CG changed the way games were designed, creating a situation where most developers was starting almost from scratch. Mizuguchi was still quite young and had no programming experience, an unorthodox choice by Sega for a new department head, but this transition now gave him a unique importance within the company. His experience with the AS-1 and VR technology put him on equal footing with his colleagues and made him an asset, despite his youth and lack of coding knowledge.

Of course, Mizuguchi would first need to find people for his team before concerning himself with how they were credited. “I borrowed space in the AM3 lab and made a team with Kenji Sasaki. I think the number of developers was about 12 people. Most were inexperienced and everyone was in their twenties,” Mizuguchi recalled. Sasaki was the perfect man for the director’s job (he also took the role of Chief Graphic Designer), as he had already spearheaded a genre-defining racing title, Ridge Racer, at Namco. Sasaki had preferred its games as a kid but did admire the scrappy, energetic image Sega presented. “I thought Sega was cool, but that stemmed more from their image than their games. Back in high school, when I wanted to grind away at arcade games, I’d go for Namco machines,” he explained in a 2025 interview. Still, the impressive technological prowess of games like Astron Belt and later Space Harrier wowed him, and his first collaboration came while serving as the Executive Vice President of Graphics Technology (GT), a CG production and games data creation company. GT handled the visual data for several of Sega’s AS-1 attractions, including the unreleased Sega SuperCoaster (1992) and Michael Jackson’s Scramble Training for the AS-1 in 1993, where he met and worked with Mizuguchi.

Sasaki’s time with Sega ended with completion of his work on the AS-1, and he took a job with Namco making videos and commercials. He wanted to work with the exciting and new 3D games the publisher was making, like 1988’s Winning Run, a first-person Formula One racer that ran on Namco’s powerful System 21 board. Winning Run was a breakthough for the genre, pushing up to 60,000 individual polygons per second. Though only modestly successful in North America, it was a huge hit in its native Japan. Namco needed people for work involving CG boards, and Sasaki’s video skills got him a spot on the Ridge Racer team. That game was the third in a line of 3D arcade racing projects that included Eunos Roadster Driving Simulator, a 1989 collaboration between Namco, the Mazda Motor Corporation, and Mitsubishi Precision. It was based around Mazda’s MX-5 (the Eunos Roadster) and used flat-shaded polygons, much like Sega’s Virtua Racing would use, but it was doing so in 1989, a full four years before Yu Suzuki’s groundbreaking title. By 1992, the game had evolved into SimDrive and now ran on the System 22 hardware. A marked evolution, it boasted texture-mapped polygons and Gouraud shading and came housed in a full-sized MX-5 shell placed in front of several large projection screens. Neither title saw wide release, and they mostly served as a steppingstone for what would be Namco’s racing magnum opus, Ridge Racer, in 1993. That title became a launch killer app for Sony’s PlayStation console two years later and even had a SimDrive-like monster version called Ridge Racer FullScale whose cabinet was a life-sized car that could sit two people!

Brief as it was, Sasaki’s Sega pedigree was still often admired by his colleagues. “Back when I was at Namco, people kept saying, ‘You used to work at Sega,’ and even when I was creating data for Ridge Racer, they’d say, ‘The visuals look very Sega-like,’ and constantly told me that the colors felt very Sega-like,” he once commented. The special atmosphere at Sega was something even noted by its competitors and was a quality that Sasaki admired. He wanted to make large-scale ride attractions, like his work with the AS-1. He also loved video games, and Sega could give him the opportunity to make both.

He didn’t take long to make the jump. After Ridge Racer FullScale, Sasaki departed Namco and went to work for Sega full-time. He was amazed at the difference in work cultures between the two companies. Sega’s staff was much larger, sometimes 30 or 40 people, compared with the five or six that made Ridge Racer, and they had greater resources.

Sasaki arrived at a critical juncture for the company. While its arcade business was still going strong, there were always the newest products from arcade rivals with which to contend. Furthermore, Sega’s new 32-bit console, the Saturn, looked like it would not only be facing a tough battle against Nintendo’s upcoming 64-bit machine but also the very PlayStation Sasaki’s Ridge Racer would soon help launch. Every arcade title Sega developed had to be something that could at least be considered for a Saturn port since the machine would need every title it could get against such stiff competition. Historically, Sega’s arcade divisions were a reliable source of titles, and the Saturn was powerful enough to bring the latest hits, like Virtua Fighter and Virtua Cop, home in great fashion. That skill would not be tested. Video games as a business had evolved greatly, and the market was now quite different than it had been when the Genesis launched back in 1988. The ensuing battle was going to be fierce and highly competitive.

The Emotion Design Lab, however, had no programmers or technical artists. Still, Mizuguchi was determined to bring the technology created for the AS-1 to a traditional video game. Once of the first things he and Sasaki did was bring in Sohei Yamamoto, an AM3 veteran from coin-op hits Rail Chase, Star Wars Arcade, and Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker. Yamamoto joined Sega in 1989 to do mechanical design for motion cabinets, but he was assigned to a programming job instead. Now, he would have his turn as a programmer to experiment with the Model 2 board. Together with Mizuguchi producing and Sasaki directing, Yamamoto rounded out the project’s leadership trio.

A New Racer Takes Position

The future of the console race may have still been in question, but even the newest machines weren’t yet capable of perfectly mimicking the latest arcade games. Thankfully, Sega had an advantage in that space. Nothing on console could match its Model 2 Pro Board architecture, a monster system that would debut with the company’s most successful arcade racer to date, Daytona USA, in 1994. Much as Virtua Racing had inaugurated the Model 1 hardware, Daytona USA was to be the killer app that would demonstrate what a powerhouse the Model 2 was. Both games were targeted at different audiences; Virtua Racing was a hit with Japanese and European followers of Formula One racing, and Daytona USA was certainly going to be the favorite among American NASCAR fans. According to former Sega Enterprises USA President Tom Petit, NASCAR was chosen because only the NFL was more popular in the country, and no other game had used the license thus far.

As great as it was, Daytona USA reportedly only used about 50 percent of the Model 2’s full power. If Sega were to produce another racer, one that would compete directly with Namco, it would have to boost that performance. Also, it would need to be universally appealing and stand out from its Model 2 sibling. Surprisingly, the team charged with such a daunting task wouldn’t be Sega’s famed AM2, the studio behind OutRun and Daytona USA. Instead, the challenge would fall to Mizuguchi’s young group of developers within AM3.

When it was founded, the Emotion Design Lab had no arcade or console parameters; Mizuguchi’s group didn’t seem concerned about profitability, but the need for new products that could make money soon became a priority. Sasaki’s experience working on Ridge Racer wasn’t something he mentioned, but word got around, and the idea for another racing game inevitably became a topic of discussion. At first, Sasaki wasn’t too keen on returning to the genre. “I didn’t want to repeat myself; I wanted to do something new,” he said in a 2025 interview. “Plus, by then, Ridge Racer was everywhere, and Daytona was only a few months away. The novelty of 3D racing games was wearing thin, so I wasn’t too keen on the idea… Looking back, I might have been a bit spoiled and idealistic.” Racing seemed to be the path of least resistance, so it became the genre of choice.

So, how could Mizuguchi and Sasaki create another racing game that didn’t fall under the shadow of its competition? The team emphasized three key points to making it distinctive:

- Emphasize impact and immersion over glossy visuals

- Include gravel roads, not just pavement

- Use muted, earthy tones to convey realism, dirt, and nature

The type of game they would make still hadn’t crystallized, but it would have to adhere to these tenets, regardless of whatever shape it took.

Time To “Rally” the Troops

Shortly after the Model 2 board’s debut, a trip to Europe would provide Mizuguchi with the impetus he needed for his new project. He visited Sega Italy and Sega France and asked for feedback on his ideas, and he was shocked to hear that they had complaints about Daytona USA. AM2’s blockbuster was one of Sega’s most successful hits ever and seemed to garner universal acclaim, but some within the company’s European staff took issue with its decidedly American focus. Mizuguchi noted the criticism, but it wasn’t until he saw a live rally race on television that the elusive concept for his project coalesced for him.

Rally racing! It was the perfect way to go. World Rally Championship (WRC) racing was quite popular in Europe, with spectators lining the edges of the courses as the cars passed dangerously close. With its off-road circuits, it could offer a fresh take on racing by avoiding the same racing format of completing laps on a closed track. Mizuguchi envisioned forests and mountainsides as possible locations, a far cry from the stadium events of Daytona and the purely urban landscapes of Ridge Racer, which he found to be cold and too precise. Sasaki liked the idea because it was a chance to mark a vivid contrast from the current crop of big racing titles in both presentation and gameplay. Off-road driving was a whole different experience, so AM3 could incorporate elements like dips and puddles, as well as the effect of gravel and other surfaces on the cars’ handling.

Mizuguchi put together a three-minute pitch video of a rally race for management in which Sasaki had mixed in different elements like forest terrain, jumps, and turns. Before they even saw it, his superiors dealt two strikes. First, rally was not a popular sport in Japan, and a game concept centered on it wasn’t something Sega management was sure it could sell. Mizuguchi’s bosses argued that rally games typically emulated the famous Paris to Dakar (Senegal) rally where competitors raced thousands of kilometers across dunes, rocks, and mud. AM3’s game was going in another direction entirely. Another problem with the concept was that the cars used in rally races were box-shaped, like regular vehicles. “Nobody wanted to make games based on the everyday car. All racing games were based around stylish F1 or GT vehicles,” Sasaki confessed. Once management saw the feature, however, opinions changed and the project was green-lit.

At first, the type of game planned was one where players raced across the U.S. from coast to coast, but creating the sensation of long-distance driving would be hard to do within the confines of the limited play time coin-op games offered. AM3 thus turned to the past works of its department rival, AM2, for inspiration. “The roots of this idea lie in Sega’s OutRun and Radmobile,” Sasaki revealed. “In particular, Yu Suzuki of OutRun said that he was inspired by the movie Cannonball Run, which was very close to the direction we were aiming for.” The team gave its project the working title of Rally California.

A conscious decision was made to avoid referencing anything from AM2’s recent NASCAR-themed hit. The team felt that if too much sourced, its game would end up being too similar, so a lot of care was taken to give the project its own look and feel. Almost as soon as work began, though, a major flaw in how Mizuguchi and other members pictured the Pacific Coast became abundantly clear: None of them had ever been to the U.S.! Sasaki recalled that the Emotion Design Lab and the rest of AM3 were separate groups, and the rally game felt like a joint project between them. There wasn’t much interaction between departments, often making things awkward because of how distant the staff were from one another. This lack of familiarity became evident in their early sketches. “When I saw the concept visual proposals that had been submitted, I felt a sense of discomfort,” Sasaki recounted in an interview with Beep21. “Even though the game was supposed to be set in America, there were pine groves, like those on a Japanese coastline. There was no sense of the dry air of the West Coast, and no matter how you looked at it, it felt like an image of ‘the Japanese sea.'” Mizuguchi decided that they had to actually see what they were drawing and planned a trip to go location scouting in the U.S. from Mexico City all the way to Yosemite National Park.

Sasaki wasn’t too enthusiastic about using valuable development time to travel because of how early in the process things still were. He knew that the game’s graphics and course layouts could benefit from the on-site research, but he was disappointed that they wouldn’t be attending any actual rally races. What he didn’t know at the time was that Mizuguchi had bigger plans than just obtaining reference materials. The trip’s primary motive was to give the team firsthand experience traveling around the vastness of the continental U.S.

Using its resources for research instead of buying equipment was one of the tenets that the small team had as a priority (its early development kit was a repurposed Daytona USA Deluxe cabinet refitted with a CRT monitor), but obtaining permission for the trip wasn’t easy. “At first, Mr. Hisashi Suzuki told me, ‘A person only travels once they’ve made a hit product!,’ which I replied with, ‘No, you’re wrong. I want to go to make a hit product,'” Mizuguchi detailed. He persisted, even committing to making the trip with his own money, until Suzuki relented and gave him a travel budget.

Mizuguchi, Sasaki, Yamamoto and graphic designers Kenji Arai and Seiichi Yamagata made the two-week trip. Another graphic designer, Kumiko Shoji, was supposed to go as well, but she was busy with Sega’s motion-simulator arcade attraction, the VR-1. The five men pressed on alone, with Mizuguchi and Sasaki taking turns driving over 1,200 miles while they videotaped and took over 4,000 photos to use as references for textures. By the trip’s end, the team finally understood what Mizuguchi had in mind. The experience provided a sense of atmosphere and scale that no photos or materials could ever match, inspiring them in ways they hadn’t previously imagined. Above all, the camaraderie of the trip washed away much of the awkwardness they had felt since the group’s formation and brought them together as a a unit. The adventure completely changed Sasaki’s perspective on how to approach the game’s track layouts. “Driving along straight roads that seemed to stretch all the way to the horizon, I was struck by the overwhelming sense of scale where the scenery never changes no matter how far you go, and I felt the difference in scale compared to Japanese landscapes and sensibilities,” he revealed.

The research trip reaffirmed the team’s belief that its concept was sound but bringing it to life was a different story. The project quickly ran into trouble on multiple fronts. First, learning the ins and outs of the Model 2 hardware was challenging, and Sasaki initially had problems getting around its limitations. He found the architecture to be what he called “temperamental” and full of quirks that required getting used to. Concerns like the availability of only monochrome textures, no support for Gouraud shading, limited texture memory, and a resolution of 496×384 pixels were all uphill battles that had to be fought, and the group worked very hard to keep these issues from becoming obvious to players. In that purpose, Yamamoto’s presence was a godsend. “He was a genius-level programmer, and getting to work alongside him on this project was a true stroke of luck. His quick thinking and unbelievable speed helped me countless times and inspired me deeply,” Sasaki admitted. Additionally, there was some consultation with AM2 regarding the hardware. Toshihiro Nagoshi used the knowledge he gained working on Daytona USA to offer modeling, texturing, and lighting tips.

AM3’s original vision was much different than what was finally produced. Several major events arose after things were well underway that altered the design of AM3’s game completely. For a time, AM3 considered using a design similar to Suzuki’s legendary OutRun, where players traveled one long stretch across changing locations, but the 1994 announcement by Midway Games of a cross-country racer of its own, Cruis’n USA, changed those plans. It was developed by coin-op legend Eugene Jarvis, and its concept mirrored AM3’s own almost completely. Much of Sega’s rally game now had to be changed, including the setting, cars, and even the gameplay.

In truth, the disruption turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Even with Yamamoto’s help, creating the giant tracks and many cars in the original game plan would have been far too complicated. Generating the continuously-changing scenery across a long-distance race would have required a huge amount of CG data that would have been difficult to load during the race. The task would have also greatly increased the project’s development time. Since the 3D CG technology of the era was capable of creating believable “sandboxes” in which players could roam, it was decided that focusing on a specific region for racing was more feasible. Similarly, smaller, narrower tracks would better emphasize control and driving skills. So, the action was confined to the Pacific Coast of the U.S. These alterations prompted a change in the project’s name to Pacific Coast Rally.

A final issue was the fact that due to the high retail cost of most coin-op games in the mid-1990s, there was an unspoken rule that games were expected to offer around three minutes of playtime per credit. A typical game of OutRun lasted anywhere between six and eight minutes, a most satisfying amount of time for players but far too long to be economically feasible for operators who wanted increased player turnover for their games. The concern was that if play time were shortened to three minutes, the rally game wouldn’t be able to provide the same value to players. AM3 had to find a flexible option that satisfied both parties, and it settled on single, one-minute laps. A play session permitted races in three different locations, so gamers could have their multi-environment experience without bogging down the game for too long. Instead of going for points based on ranking or beating a specific time, the goal was to reach first place by the end of the third course. “As you play more and get used to the controls, and are able to drive as you want, you can see a bigger goal like ‘complete three races and win,'” Sasaki detailed. “Even if you fail, it’s easy to create situations that make you think, ‘I was so close to achieving (my immediate goal),’ such as timing out just before the finish gate, or finishing without being able to overtake the rival in front of you, and this will motivate you to insert your next coin.”

A Legend Is Born

Thanks to its high popularity and constant presence on television, NASCAR gave Daytona USA at least a minimum level of familiarity to players who may not have been devoted followers of the sport. WCR didn’t have that advantage. Those who weren’t fans may not have understood its rules, so AM3 had to design its rally game to be accessible to everyone. Generally, people use the term “rally” as a short form of Special Stage (SS) Rallies, where drivers competed against each other through time trials on individual special stages with the overall winner calculated based upon their total time to complete all of the stages involved. AM3 made its title more similar to “Super SS” events since it was a competition between different vehicles on short, specially-constructed stages.

The action was confined to a rally of three courses that spanned different skill ranges: desert (beginner), forest (intermediate), and mountain (advanced). Each one’s design sprouted from the seed of an actual location. A fourth bonus course called lakeside was based on the beauty of northern Europe but could only be unlocked if players were able to attain first place by the end of the third mountain circuit. The desert stage was AM3’s version of the 3,100-mile Safari Rally held in Kenya, considered one of the toughest events in WRC. It combined imagery of an African savanna, complete with zebras and elephants, with landscapes taken from AM3’s North American road trip. The forest course came from Sasaki’s determination to add the expansive wilderness of California’s Redwood National Park to the project. In 2021, he revealed that although it was nearly finished, it had to be changed to Yosemite National Park because “a game released by another company had a stage with almost the same image.” The image was presumably of Midway’s Cruis’n USA. There could have also been a fifth track, as Mizuguchi, who lived near Mt. Fuji in Yokohama, wanted to also include a snow-covered track as a homage to the long mountain walks he used to take as a child. Time and resources kept it from being implemented, but it would make it into the sequel.

Given the limited number of tracks that could be included, many of the the environments AM3 encountered on its research trip were left on the cutting room floor. Some were quickly discarded because they would be too difficult to convert or just didn’t excite the team. Others didn’t make the cut because they clashed with AM3’s mantra of distinguishing its game from others already on the market. For instance, the Grand Canyon, despite its wondrous beauty, was one of the highlights of the journey and awed Mizuguchi and the others, but it wasn’t included because Daytona USA already had a track with similar scenery.

Not all the tracks were so easily conceived. Game development can be exhaustive work, often leading to developers second-guessing their own efforts. Sometimes, one has to step back for a bit and refocus before continuing. At one point, Sasaki became convinced the game would fail and lost confidence in its potential. He was constantly thinking about cars and obsessing to such lengths that he couldn’t see why people would find rally racing attractive. He took a drive into the mountains to clear his head and enjoyed it so much that it recharged his enthusiasm and gave him an idea for a mountain-based course. That idea made it into the game based on the Tour de Corse, a rally from Corsica, France and inspired by Kumiko Shoji’s love of the Mediterranean region of Europe. She watched videos and examined photos of the area, particularly those of European townscapes. “I tried my best to make it look real rather than like a drawing or photo, giving consideration to the textures and other elements so that it would leave a realistic impression overall,” she recalled.

All three initial tracks could only be played individually in Practice mode, where players raced two laps against one other car, but Championship mode was where the heart of the game lay. Whereas Practice mode only permitted competing against a single car, Championship mode started players in 15th place at the bottom of their category. Time was the true enemy, with the rival cars serving as little more than obstacles to be avoided. Making each checkpoint before the time limit expired required serious practice and commitment.

During gameplay, there was no mini-map onscreen to guide players, but much like real rallies, where around 70 percent of the track information drivers receive comes from the navigator, Pacific Coast Rally instead used traditional audio cues (recorded by Sega of Japan development tool programmer and computer graphics artist Kenneth Ibrahim) to know when curves or changes in elevation were coming. Imagine being in an arcade playing some cabinet and hearing a booming “easy right!” or “over jump!” from across the room! If the sound were too low or if players were too engrossed in their driving, there were also marker symbols in the form of color-coded arrows (blue, yellow, and red) and exclamation marks to guide them.

Even with all the detail AM3 put into the courses and gameplay, it wasn’t trying to make a completely accurate WRC game. For example, real WRC rallies never had racers compete together on the course to reduce the danger of crashes. Each raced individually and competed for the best time. Since that was not a factor in an arcade game, Pacific Coast Rally put all competitors together during the race to make things more thrilling. Races could be incredibly intense as players fought to overtake rival cars and reach each checkpoint before time expired. Interestingly, Pacific Coast Rally wouldn’t be the first Sega rally game to have rivals; 1984’s Safari Race had a similar set up and even added wild animals to avoid. This time, however, all the rally action was in beautiful 3D. To make the deal even sweeter, all the cars were licensed – potentially making Pacific Coast Rally the first video game to do so – including the Lancia Delta and Stratos and the recently-launched Toyota Celica ST205, which won out over the Supra because Mizuguchi thought it was a more interesting car.

About those licenses… It might seem like an easy decision for Fiat and Toyota to give Sega a licensing deal to include the Lancia Stratos HF and the 1992 WRC-winning Delta, but it turned out to be quite difficult to get both companies onboard. Mizuguchi had his heart set on specifically including the Delta and Celica because while both were championship vehicles, they had never directly competed against each other. AM3’s game could serve as a sort of fantasy match between them; however, when he went to Toyota’s offices to show their management his pitch video for including the Celica, he initially received a resounding “NO” as an answer. He was told that the video game industry wasn’t considered a real business and didn’t have a viable means of publicity. Toyota argued that people who played video games didn’t run out to buy cars. Mizuguchi decided to let his video speak for him, and its 3D and textures changed the tone in the room instantly. Toyota’s leadership couldn’t believe they were looking at a video game. They agreed to license the Celica with the condition that Fiat had to agree as well. Mizuguchi took his video to Turin, Italy, where he basically told Fiat that Toyota had already signed on, even though it hadn’t. Luckily, Fiat gave its blessing, and AM3 had its licensed cars. The best part? It got them without any licensing fees. Fiat was so pleased with what it saw that it also allowed AM3 to include sponsor names on the Lancia Delta, a concession Toyota granted as well.

It was fitting that AM3 included the Lancia Stratos, a rally legend with more wins than any other car and four consecutive championships. The team included it after gathering feedback from consumers and finding it to be the most popular vehicle. Mizuguchi wasn’t surprised at the Stratos being named so prominently. “In Japan, when I was a child, there was a supercar boom, and everyone had rubber erasers shaped like cars. All Japanese children had lots of rubber cars, and everyone knew this car, its name, and its details,” he recounted. Known as the “King of the Desert,” The Stratos controlled differently than the Celica and Delta because it had two-wheel drive. The Stratos was faster but more difficult to handle, making it the most advanced of all the cars available. AM3 understandably kept it as an Easter egg that had to be unlocked with a series of steps at the start of the game. Owners of the later Saturn port had an easier time and could unlock the Stratos after completing the Championship mode.

One of the big Model 2 issues Sakamoto helped resolve came from rendering those very cars. The Lancia wasn’t difficult to create in polygonal form, but the Celica proved to be problematic because the Model 2 hardware was incapable of smooth shading. To create the illusion of curves, the team added curved-looking textures to flat polygons, such as with the cars’ tires, which were just octagons. Shadows were applied to each one using textures, and when in motion, the tires looked round. Resources were limited, so it made little sense to allocate them to such minor details when there were other ways to create the illusion.

Sakamoto’s biggest challenge was making the cars handle correctly. As mentioned earlier, the game was not designed to be a true recreation of WRC racing. This factor was paramount when designing how it would control, so AM3 made the handling a lot more novice-friendly. “We didn’t want to make it totally realistic because if we did that, most players would find themselves going totally out of control around every corner,” Sakamoto commented. AM3 also removed crashes or going off-course in the Championship mode. So, even though there were spectators along the sides of each of the tracks, there was no way for players to hit them.

Drifting around turns was a major part of rally racing, and Sakamoto made sure to center gameplay around it. Thanks to the game’s analog control, both the Celica and Delta drifted differently when used with an automatic transmission, depending on how players braked and steered. Manual transmissions were harder to master but offered better control overall. “I want players to utilize real driving techniques, braking just before a corner, shifting down from four to three to two, just as though they were driving a real car,” he commented. Often, no brakes were required for most of the tracks because the cars would begin to drift when players shifted down while steering. Tighter drifts could be obtained by lower and more abrupt downshifts. Gear drifting was an element taken from Daytona USA, although that game used a different and more complex technique.

The Sound of Victory

AM3 set its racing to a terrific soundtrack by Takenobu Mitsuyoshi, who had composed the now-classic themes for Daytona USA. His work on that release was almost an accident, as was his career in video games. As a teenager, Mitsuyoshi was never really a fan of console games, having preferred to play on PC. It was in college that he began to play PC Engine and Famicom titles – nearly failing his undergraduate thesis because of his love of the Famicom strategy game SamGokuShi: Chuugen no Hasha – but he never spent much time in arcades.

During his senior year, he struggled to find something that interested him. His degree in economics would have likely landed him a position at a bank or as a store manager, but Mitsuyoshi didn’t find such work appealing. He tried teaching but soon found that it didn’t suit him either. It was then that video games came into the picture. While riding in a car with a friend, a song came on the radio that immediately caught his attention. It was purely instrumental, a fusion of jazz and funk that was overflowing with synthesizer-like tones. He had to know who the musicians were and was stunned when his friend explained it. “To my surprise, he told me it was performed by a band called S.S.T. Band, made up of members from the sound development department of a video game company, Sega. The music being played was an arranged version of tracks from their games.”

Musicians? For video games…? Impossible! Yet it was true, and the reality fascinated Mitsuyoshi. His future was decided: he would enter the video game industry. He applied at several companies, including Namco, Tatio, Konami, and Sega, but only the latter two agreed to interview him. Sega, being the home of the S.S.T. Band, made it an easy choice. Over the next few years, he worked on the sound or composed music for several titles, like G-LOC Air Battle, Virtua Racing, and OutRunners. His rise to fame came with Daytona USA, when AM2 decided to include vocals in the game’s soundtrack. Mitsuyoshi never considered himself a singer but gave it a try and his songs like “Let’s Go Away” and “King of Speed” became classics among Sega fans. His place at Sega was cemented when Yu Suzuki asked him to sing a few songs for vocal album for a promotional campaign for Virtua Fighter 2.

For AM3’s rally title, Mitsuyoshi had a bit of a head start because the game used some of the same sound drivers as Daytona USA. For that game, vocals were sampled, broken down into segments, and then assigned to different keys for playback. AM3’s game, however, had more refined version of the Model 2 board and could now sample longer phrases, the most famous of which was the end jingle. “That’s why the ‘Game Over Yeah’ jingle you heard when the game ended wasn’t split into separate parts. Instead, we sampled the entire phrase as‑is and used it directly in the game,” Mitsuyoshi revealed. He didn’t intend on adding the “yeah” at the jingle’s end; it just sounded good and fit the atmosphere. Since working on Virtua Racing, he had established a rule that he would sing the words “Game Over” in each title, as he later did for Daytona USA. He simply repeated the process for Pacific Coast Rally, and it somehow became iconic. To this day, he still has fans talk about it, including one industry professional at the 2024 Game Developers Conference who confessed that the jingle made him feel less frustrated about not finishing a course when playing. He told Mitsuyoshi that it encouraged him to keep trying.

Mitsuyoshi soundtrack wasn’t the only part of the audio that received special attention. AM3 went to great lengths to recreate the specific sounds of rally racing, including driving a real rally car. Mizuguchi booked time at the Maruwa Autoland Nasu dirt track in the Nasu Highlands region of the Tochigi Prefecture so that AM3 composer and designer Tomoyuki Kawamura could record from a real car. Three All-Japan Rally spec cars were prepped for recording: including a Celica GT 185 and the newer 205 model with an IF engine configuration (common for performance rally vehicles prepped for WRC and All-Japan rallies). It was from this monster of a car that Kawamura grabbed engine idling, revs, and exhaust sounds. Afterward, different AM3 members rode shotgun in the Toyota Celica driven by Masayuki Ishida of the Japanese rally group Team C-One Sport to capture video footage from the cabin perspective with an 8mm camera and to record braking and drifting sounds, as well as environmental noises like gravel splashing against the car (the Lancia Delta’s engine sound was recorded from Mizuguchi’s own car). As Ishida zipped around the track, the AM3 team began to get a better understanding of how the car handled and reacted to the track environment. “The more test drives I took,” said the journalist from Gamest magazine who covered the event and rode along, “the more I noticed the mud marks on the side of the car, the way pebbles were kicked up by the tires, the way dust rose, and the car’s subtle behavior.” Everyone was exhilarated during each lap, but they were shocked when Ishida confessed that he was only going about half the car’s top speed.

The sounds would then be reproduced during gameplay using a technology AM3 called the Active Shock Generator (ASG), a proprietary system that used sound to create vibrations. The ASG moved the cabinet’s seat in relation to the car’s movement on the road, and it reacted when players hit other cars. Sega’s AM5 division added two ASG motors, providing a higher sense of immersion than Daytona USA, which had only one. With the ASG, AM3 was able to make the audio an integral part of its game’s immersion.

Once the sounds were recorded, the team then took turns driving the both the newer and older Celicas themselves to get the feel of what the car felt like in motion. Mizuguchi got so excited when it was his turn driving that he misjudged a turn while drifting and crashed, damaging the rear bumper. Despite the mishap, he felt the experience was worthwhile. “We took out insurance, so if we damaged the vehicles, it wasn’t a big deal,” he laughed (in hindsight, of course). “There was a bit of damage, but this kind of experience was essential. It allowed us to learn how the car reacted when we made it skid and slammed on the brakes suddenly. It allowed us to understand every movement caused by a particular driving technique.”

Another result of the experience was one more change to the game’s title, the result of AM’s procurement of licensed cars. Official cars on fictional tracks made the Pacific Coast Rally name no longer seemed appropriate. Near the end of its 10-month development cycle, Koji suggested that the game’s title be changed to Sega Rally Championship 1995. It was adopted, though the year would be dropped for its western release.

3… 2… 1… Go!

When Sega Rally Championship was put out for location testing at local game centers, Mizuguchi and the team spent a great deal of time watching and gauging people’s reactions. They were ecstatic to see that while people would swear when they lost or even kick the machine, most came back to play it again. That slow burn engagement was constant, and the full effect was visible at the 1995 Amusement Operators’ Union (AOU) Show in Tokyo, Japan. Over the course of several days, lines queued up to play Sega’s newest offerings, and Sega Rally Championship was the star attraction.

That kind of reaction is impressive and a vindication of Mizuguchi’s belief that arcade rally games could be popular. It’s important to consider that AM3 achieved such results despite the fact that aside from its time with Team C-One Sport, it didn’t consult with any other WRC professionals during Sega Rally Championship’s development. It wasn’t until after game was completed that anyone really associated with the sport gave an opinion on the product. Two professional drivers, Juha Kankunen and Didier Auriol came in and played against some customers. Both men were actual drivers of the cars featured in the game, Kankunen of the Lancia Delta and Auriol of the Toyota Celica. Reportedly, they enjoyed themselves during their time with Sega Rally Championship, and Auriol even wanted to purchase a cabinet for himself. Sadly, Sandro Munari, who raced in the Lancia Stratos from 1974 to 1978, didn’t join them. It would have been a terrific event to have the three legends compete against one another using the included cars.

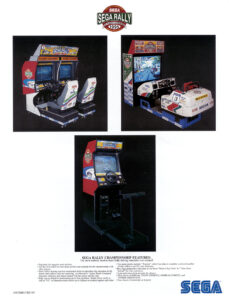

When it launched into Japanese arcades in February 1995, Sega Rally Championship was available for sale in three different cabinet types that incorporated a force-feedback steering wheel to make drifting and driving on changing surfaces exciting and physical experiences. The most commonly found were the standard upright that just had a steering wheel, four-gear shift stick, and pedals and the Twin unit, which was sold in pairs and had two-player capability. Along with the upright, it was the most common type encountered in arcades. King among the variants but much rarer was the Deluxe cabinet. Model 2 arcade machines usually sold for around $15,000 and the $22,000 price tag of the Deluxe version typically kept it confined to larger game centers. It was a sight to behold, with players sitting in a mini Celica replica that could pitch and tip. Although the Deluxe model included a built-in clutch, two speakers in the front and rear, and a subwoofer under the vibrating seat, the Twin cabinet became the more popular version, likely to its lower cost and multi-player link capability. It would retain its charm years after release, found in even small arcades around Japan.

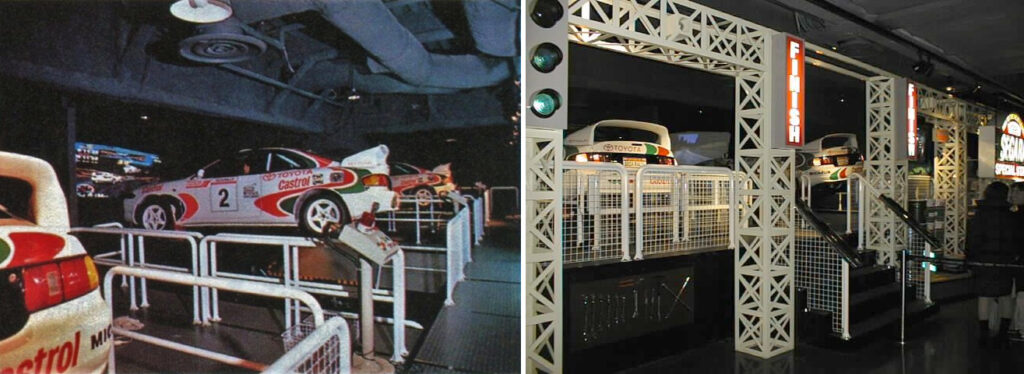

Perhaps the best way to experience everything AM3 brought to Sega Rally Championship was with the fourth model, the Special Stage version. For anyone outside of Japan, though, doing so was unlikely. It wasn’t sold at retail and was a monstrous ride-style attraction built by Sega AM5 exclusively as an opening-day attraction for its Shinkjuku Joypolis amusement center that featured three heavily modified, rally-spec Toyota Celica GT-Four cars, each equipped with a projection screen right in front of the windshield. More of a motion simulator than arcade game, the gargantuan ride could move along a fixed axis in six different directions, the first Sega attraction to do so. The two extra axes made it possible to recreate almost any kind of movement, shifting Sega’s large-scale attractions from the passive experience of the AS-1 to an interactive one because the motion changed based on how players moved during gameplay. Granted, Special Stage was not the first Sega game to do this, as Yu Suzuki had long been working in that direction with his taikan games, but it was the first to do it on such a huge scale.

Some extensive changes were made to how this version played, such as the removal of different camera angles and the multiplayer linking capability. Likewise, players could no longer choose the Toyota Celica GT-Four or the Lancia Stratos HF. Regarding the cabinet itself, not everything from the Deluxe version transferred to Special Stage intact, but there were some added amenities. AM5 had to remove much of the original car components, but the full-sized car’s seats were large enough for two riders to enjoy the thrill together (for an extra cost, of course).

Special Stage was designed to closely resemble the stock Sega Rally Championship game, but the much larger cabinet gave it the same sense of immersion of the taikan games that Mizuguchi enjoyed so much before joining Sega. As far as is known, Special Stage was only found at Sega’s Shinjuku Joypolis venue, and sadly, since that location closed in August 2000, no working units are known to have survived. That said, the amazing technology behind Sega Rally Special Stage didn’t just vanish. Its motion and simulation systems were a major influence in Sega Touring Car Championship Special, the first project by Mizuguchi’s next studio, AM Annex. The technology was used once more, albeit in a more polished form in 2007 with Initial D Arcade Stage 4 Limited.

Regardless of the model, the Championship mode was reportedly the most popular with players, with most casual attempts ending in the forest and players with a modicum of skill getting to at least the mountain course before running out of time. To many who tried, not finishing the game wasn’t considered a failure. Sega Rally Championship was a strict, with time settings that could be unforgiving to unskilled competitors. Many Japanese players considered simply completing the mountain stage to be an achievement.

Starting in the Pole Position

Upon release, Sega Rally Championship quickly drew a following, selling around 12,000 units. That number is less than the 2D racer OutRunners, which came out two years earlier, and it was far short of the stellar 40,000 mark set by UFO Catcher in Japan, but it was an excellent start for a rally game made by young and mostly inexperienced developers. It was also enough to guarantee the Saturn port that fans clamored for and one that game magazines had been asking about since before Sega Rally Championship even made its arcade debut.

The Saturn port in 1996 was one of the console’s major attractions and gave the game extra life by allowing three laps per track instead of one and adding the Lancia Stratos as an extra car that could then be used in regular play. It had some compromises, like a lower resolution and framerate and rougher textures, but it compensated with split-screen play and adjustable settings for steering, tires, and front and rear suspension. AM3 also added a Time Attack mode and replays for all courses. Sega even released a Netlink version (the Japanese version, Sega Rally Championship Plus worked with the Saturn Xband modem) that included online play. Sega then brought the game to PC in 1997, which, despite its demanding specifications for the improved visuals, added connectivity for two-player matches via LAN or online.

Overall, many fans to this day identify Sega Rally Championship as one of the best racers of the 32-bit era. Its sequels would appear in arcades on Sega’s Model 3 board and on the Dreamcast, as well as on Xbox, PlayStation 3, and PC. Even the N-Gage and mobile phones saw their versions of games in the Sega Rally Championship series. AM3 had created more than just an incredible racing game; it launched a franchise.

AM3’s masterpiece also influenced other rally racers, like 1998’s Colin McRae Rally by Codemasters on the PlayStation. The producer of the first four games in that series, Guy Wilday, explained how the car handling in the original Sega Rally Championship served as the foundation for how the first Colin McRae Rally controlled. “Everyone who played it loved the way the cars behaved on the different surfaces, especially the fact that you could slide the car realistically on the loose gravel,” he explained. “The car handling remains excellent to this day and it’s still an arcade machine I enjoy playing, given the chance.”

Along with starting a new game series, Sega Rally Championship also kicked off Tetsuya Mizuguchi’s video game career. The project taught him a lot about how video games are made from a technical perspective, as well as from a marketing standpoint. “Racing games are structurally simple in the first place,” he explained. “It was a really good way to learn how to make video games. There is no doubt that the trial and error then became the basis of my own game design methods afterwards.” He pooled that knowledge and experience with what he learned from his time at the Emotion Design Lab as the producer for Manx TT Super Bike, the 1996 motorbike racing game made in collaboration with Sega’s AM4 group. Eventually, he convinced Hisashi Suzuki to let him take a half-dozen or so members from AM2 and AM3 and create his own design team, AM Annex later that same year. That group eventually increased to around 15 people, but the intention was always to keep it small. “We didn’t want a big team. Our goal is to get respected creators working together,” Mizuguchi clarified. AM Annex developed games like Sega Touring Car Championship and Sega Rally 2 before Mizuguchi transitioned to the home console space to develop games like Rez and Space Channel 5.

“Game Over, YEAH!”

Anyone who has a chance to play Sega Rally Championship in its coin-op form should absolutely do so, especially if the machine is the Deluxe unit (there’s no practical way for anyone to play the Special Stage unit anymore). The Saturn port is an amazing conversion that, paired with the Arcade Racer steering wheel, is an immense amount of fun. It has a remixed soundtrack by Naofumi Hataya that many gamers prefer over the arcade version’s.

With Sega Rally Championship, AM3 proved that there were other talents outside of AM2 that could create racing greatness. Its appeal was universal, with players of all ages and backgrounds enjoying the intense rally action that made the game so different from its contemporaries. Mizuguchi saw the love people had for his rally classic firsthand while on a trip to Europe after its release. “I saw Sega Rally in a shopping center in the Spanish countryside, with a child at the wheel, his father stepping on the accelerator, and his grandfather operating the clutch,” he fondly recalled. “I never imagined people would play it like that, I’m sure they’d talk about this game over dinner at night.”

Sega Rally Championship stands to this day as one of Sega’s highest benchmarks for arcade racing quality. The game brought something different to a genre that was saturated with competition, giving it a much-needed shot in the arm and bringing the fun and excitement of rally racing to new audiences all over the world. AM3 brought all of those qualities to the Saturn version intact, but the coin-op original is where the magic first enamored consumers, and it remains the purest way to play. As good as the sequels may have been, they never managed to completely recapture what made the first Sega Rally Championship so special, and that distinction makes it such memorable part of Sega’s history.

Sega-16 would like to thank Andrej Preradovic for his translation work with sources for this article.

Sources:

- Barder, Ollie. “Takenobu Mitsuyoshi on His Game Music Career and Iconic Game Over Jingle.” Forbes. November 28, 2025.

- “Beep21 Interview with Takehito Sasaki: Sega Hard Historia Complete Edition.” Beep21. March 16, 2025.

- “Behind the Scenes: Sega Rally.” GamesTM. 11 Oct. 2022.

- end585. “Otaku: The Cinema of Reality. YouTube video. 1994.

- Dickreuter, Raffael, Bernard Lebel, Will Mendez. “Interview with Michael Arias.” XSI. September 26, 2003.

- Edge Staff. “The Making Of: Colin McRae Rally.” Edge. February 5. 2010.

- —. “The Making Of: Sega Rally Championship 1995.” Edge. October 2, 2009.

- Game Informer. “78 Rapid-Fire Questions with Tetris Effect’s Tetsuya Mizuguchi.” YouTube video. October 28, 2018.

- “Gensen Factory: Sega Rally Championship.” Saturn Fan. March 1995.

- Horowitz, Ken. The Sega Arcade Revolution. Jefferson: McFarland. 2018

- “Interview: Rez Creator Tetsuya Mizuguchi’s Universal Life Evolves Humanity. ‘Creativity Is NOT Born from Limitation.'” Denfaminicogamer. June 12, 2017.

- “Kenji Sasaki’s Game Wanderings Vol. 1: First Release Images from Sega Rally Presentation 30 Years Ago.” Beep21. March 23, 2025.

- “Kenji Sasaki’s Game Wanderings Vol. 2: Challenges and Trial and Error with New Game Systems.” Beep21. August 28, 2025.

- Kenji Sasaki’s Game Wanderings Vol. 3: The Forced U.S. Research Trip Before Developing ‘Pacific Coast Rally.'” Beep21. December 25, 2025.

- Kurokawa, Fumio. “Fumio Kurokawa’s Entertainment Legends Vol. 8: Tetsuya Mizuguchi (Part 2): The True Reason a Genius Creator Made Games.” What’s In, Tokyo? September 26, 2017.

- “Next Generation Alphas: Sega Rally Championship.” Next Generation. April 1995.

- “Next Generation Alphas: Sega AM Annex.” Next Generation. November 1996.

- Ogasawara, Nob. “Behind the Scenes with the Makers of Sega Rally.” EGM2. February 1995.

- “Recording the Sounds of Sega Rally Championship.” Gamest. January 15, 1995.

- Sasaki, Kenji (@sasappo). “At the time, from the company’s perspective, the project was being handled by a mysterious producer with no experience in arcade game development.” X. March 9, 2020, 9:01pm.

- Sasaki, Kenji. (@sasappo). “Originally, the forest stage was based on Redwood National Park and was almost finished.” X, November 11, 2021, 9:59pm.

- “Sega ATP Attraction Design Works No. 4: Sega Rally Special Stage.” Sega Magazine. April 1997.

- “Sega PC World Close Up: Sega Rally PC Port.” Sega Magazine. March 1997.

- “Spring Sega AM Rush!!” Sega Saturn Magazine. April 1994.

- Swan, Gus. “Inside Sega Amusements.” MeanMachines. August 1994.

- Temple, Tony. “The Last Ridge Racer.” The Arcade Blogger. November 20, 2022.

- THG Editorial Office. “Real3D: An Interview with Jon Lenyo in Late 1998.” THG. October 22, 1999.

- Toyotomi, Kazutaka. “Sega Arcade Memories: Sega Rally Championship.” Beep21. March 17, 2025.

Recent Comments