As gamers, we’re always looking for freebies and special offers. Everyone likes to get a poster, soundtrack, or art book when they reserve or buy a game; and to be honest, you can’t honestly blame them. Imagine then, if you were to have been offered a free subscription to a magazine that only covered the console you liked best — and it was published by the manufacturer itself. Still doesn’t sound appealing? Ok, let’s up the ante. Imagine that said manufacturer was also one of the best software publishers in history and was also a fierce underdog out to wrest control of the industry from the longtime king of the mountain. Better? Still not enough, eh? Ok, what if I just told you this was a strategic advertising ploy designed to do nothing more than put software in people’s homes? That sounds more realistic, to be sure, but it’s not too attractive to the bright-eyed gamer looking for scoops and special features about his shiny new console.

That is the tragedy of Sega Visions Magazine, one that reeks of poor planning and wasted potential. From its early days as a free pamphlet to its finale as a feature-packed periodical, Sega Visions saw some decent growth, despite having just about everything going against it. The saddest part of it all is that its death reflected a situation that everyone knew was spiraling out of control…everyone but Sega itself.

A Vision for the Future

The true origins of Sega Visions Magazine can be traced back to the 8-bit generation and the overwhelming one-sided battle that was being waged for dominance. Being outsold in America by almost 16-to-1, Sega tossed its withering Master System headfirst into its grave by passing along the marketing and advertising rights to a clueless Tonka. After three years of dismal sales, it grudgingly took back control and repackaged the console for one last shot at success. To compliment its new look and attitude, the Master System received a promotional mini magazine called the Team Sega Newsletter. It was nothing special really, and wasn’t truly intended to compete as a true periodical. It was a promotional item, an advertising gimmick, which was designed to garner interest in the Master System II. It had some cool features, like an article by Steve Hanawa about how the 3D goggles worked, and it even sported a few offers. The Newsletter was the only place to score a copy of Power Strike, one of the best 8-bit shooters ever made.

The true origins of Sega Visions Magazine can be traced back to the 8-bit generation and the overwhelming one-sided battle that was being waged for dominance. Being outsold in America by almost 16-to-1, Sega tossed its withering Master System headfirst into its grave by passing along the marketing and advertising rights to a clueless Tonka. After three years of dismal sales, it grudgingly took back control and repackaged the console for one last shot at success. To compliment its new look and attitude, the Master System received a promotional mini magazine called the Team Sega Newsletter. It was nothing special really, and wasn’t truly intended to compete as a true periodical. It was a promotional item, an advertising gimmick, which was designed to garner interest in the Master System II. It had some cool features, like an article by Steve Hanawa about how the 3D goggles worked, and it even sported a few offers. The Newsletter was the only place to score a copy of Power Strike, one of the best 8-bit shooters ever made.

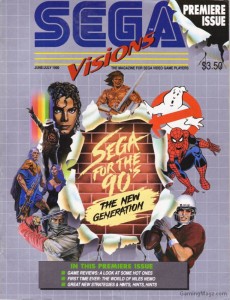

Time passed, and the Master System support was slowly trickling to a stop as the new Genesis console began to pick up steam. In June of 1990, Sega repackaged the newsletter as the first issue of Sega Visions, a bimonthly magazine for the next generation of gamers. Published by the Communiqué Group and headed by Bob Harris and Al Nilsen, it was offered freely to gamers who registered their Genesis or Master System with Sega. Published four times a year, Sega attempted to convince readers that it was a legitimate journalistic source, when it was, in fact little more than a controlled hype machine, and it was apparent that the new publication was meant to be considered a fresh start. From the outset, Sega tried to put its new hardware over the aging Master System, and while those who still stubbornly held on to their 8-bit consoles could count on minor support from the new periodical for the moment at least, Sega made it all to clear that it wanted their Master System users to upgrade to a new Genesis. Power Base Converter offers were multiple (like the “graduate to Genesis” offer in issue #1), and coverage of the aging machine was steadily reduced with each issue.

The first issue of Sega Visions wasn’t anything particularly special. It had more than a passing resemblance to the original Team Sega Newsletter, only it was pitching the Genesis instead of the Master System. It was thin, and the $3.50 cover price was confusing, since the magazine was never really sold at retail. From the outset, the gimmicky philosophy it touted was obvious. For example, it included the first in a series of poorly illustrated trading cards that were intended to be based on reader’s cheats and hints; however, they were dropped after only a few issues.

There were other signs of Sega’s intentions too. Most of its paltry thirty-two pages were taken up with the typical Sega bravado of the era. Sega for the ’90s: The New Generation and the Sega Decade is Here were supposed to convince gamers that the company was bigger and better than ever, ready to conquer the world. In Sega’s defense, its prediction for the 16-bit generation came true, but this was hardly the result of its incredibly narrow marketing. The two-page introduction by new president Michael Katz thanking supporters and hyping new releases was echoed by other pieces championing Sega’s arcade experience and eagerness to bring it home. We’d seen it before, and it didn’t really impress anyone.

To be fair, Sega did a great job of consoling Master System owners, and early issues included reviews for the few new games that were quietly released. Of course, anyone who wasn’t planning to buy a Genesis was going to find fewer reasons to keep reading as time wore on. Releases for the dying hardware were practically non-existent at this point, but it was nice to see that Sega hadn’t totally forgotten about its 8-bit supporters. The writing was on the wall, however, that the Genesis was the future.

While Sega Visions didn’t initially seem like anything new, the seeds for the future were being firmly planted. What gamers didn’t know that years later Sega would rip it out from the ground by the roots.

An Identity Comes into Focus

One thing should be made perfectly clear: Sega never intended for Sega Visions to become a legitimate periodical, something Nintendo set out to do from day one. It was a marketing tool, nothing more, and as Bill Kunkel stated in our interview, the company made no effort to hide that fact to its staff. Even so, the editors did the best they could with what they had. The small group really tried to add some personality to a product that received no love from its creator, but their work was hampered by the lack of cooperation they received from Sega as a whole. Imagine trying to run a magazine without being permitted to say anything negative about any of the products you cover or without any sense of exclusivity at all. It’s not easy to come up with an interesting feature about a certain game when the publisher is pimping it everywhere else.

All of this stems from the fact that Sega Visions was never truly planned as a stand-alone periodical by its maker. Sega as a company had a strict vision of where its marketing was headed, and this was pushed forward by even stricter budget constraints. Former Head of Global Marketing Al Nilson told Sega-16 “Bob Harris was the editor-in-chief from the Sega side and he ran with it, but in terms of seeing where this could go, you know, like could this be a stand-alone magazine and be something bigger, I don’t think it ever got the attention or a lot of attention from within Sega. A lot of it was because of the budget and how much it was going to cost us to go and make this something bigger. Was the expertise around to be able and go and do that from our standpoint? We had created a fine product, a fine editorial product, but taking it to that next level was something that just wasn’t paid attention to that much.”

In truth, Nintendo was spending about eight marketing dollars to every one Sega did, so there was never a real chance in the beginning to expand the magazine. “It was a very costly product for us,” Nilsen explained. “A lot of times it was just a question of what do we do with the limited budget dollars that we have? Are we able to get the best bang for our buck right here?” Lacking the retailer presence Nintendo had with its massive World of Nintendo stores, Sega had to be very choosy with its marketing. It wasn’t easy to publish a magazine while you’re looking at less than ten percent market share.

In truth, Nintendo was spending about eight marketing dollars to every one Sega did, so there was never a real chance in the beginning to expand the magazine. “It was a very costly product for us,” Nilsen explained. “A lot of times it was just a question of what do we do with the limited budget dollars that we have? Are we able to get the best bang for our buck right here?” Lacking the retailer presence Nintendo had with its massive World of Nintendo stores, Sega had to be very choosy with its marketing. It wasn’t easy to publish a magazine while you’re looking at less than ten percent market share.

The interesting thing about this whole situation is that even with all the backstage problems that plagued Sega Visions, many gamers still viewed it as a real magazine. The comparisons to Nintendo Power were constant, and this actually gave it a legitimacy that Sega never did. Perhaps this is what motivated the editors to try and give it a sense of identity that Sega never would have done on its own. After all, it couldn’t control everything, could it?

Actually, it could. Sega decided which games were to be covered, and what peripherals were to be hyped. What this basically meant was that the staff was denied full journalistic freedom, and this restriction hurts Sega Visions‘ quality immensely. How can you put together a great piece on a particular title or accessory if there’s no way the bigwigs upstairs will let it get to print? Still, Sega enjoyed flaunting its new mouthpiece. For instance, each issue included a section called Party Line that sounded off each third party licensee’s upcoming releases, placing as much emphasis on the company itself as on the games. There was no shortage of mention of the Sega Seal of Quality! Even the layout itself had corporate logos all over the place, another example of the excessive saber rattling that permeated each issue.

Despite the in-house censorship, the editors became pretty creative. During its first two years, the magazine underwent some serious changes. Several sections were eliminated (including Niles Nemo, who was replaced by the first Sonic comic strip), and other areas were expanded. Reviews received a major facelift, and more space was given to strategy. Readers were also allowed to see how things ran behind the scenes, like how motion capture was done and the making of Jurassic Park (in the June/July 1993 issue). Like any other gaming publication, there were some errors (like the use of Greatest Heavyweights screen shots for the Evander Holyfield “Real Deal” Boxing review in issue Aug./Sept. 1992 issue. This was a review, not a sneak peek). Also, virtually everything was viewed in a positive light, and almost nothing negative was ever allowed to be mentioned about any title covered, no matter how obvious it was. Needless to say, this was blatantly apparent to readers. Did anyone really think the editors were genuinely excited enough about the Activator to give it two whole pages?

Yet even with all these problems, the magazine managed to slowly grow until it was generally three to four times the length of its first issue.

Gone Before Its Time

After some time, the decision was made to move Sega Visions to the San Francisco, which meant the end for the current staff, including the publishers. Under the new management, Visions was further refined, but was cancelled shortly thereafter, and no one but the publishers know why. It most likely had to do with the war raging within Sega between its American and Japanese divisions. SOJ’s head Hayao Nakayama made the controversial decision to discontinue all hardware in 1996 to concentrate on the Saturn, and Sega Visions was likely killed as a cost-cutting measure. Considering the debacle that was the Saturn’s U.S. launch and subsequent battle against the Playstation, perhaps the decision to cancel was premature. Sega found itself in almost the exact same position in 1996 as it had in 1990, and any and all advertising would have helped but given that the company was hemorrhaging cash at this point, it just wouldn’t have been practical. Sega Visions demise was also hastened by the fact that it was free, and this burden probably made it a prime target for executives looking for extra cash to throw at the embattled Saturn. Had Sega instituted a marginal subscription fee when sales began to take off, Sega Visions might have found the solid financial ground it needed to stay afloat.

Perhaps the saddest part is that despite the questionable corporate decisions made by an increasingly out-of-touch Japanese management, despite the constant comparisons to Nintendo Power, and in spite of all the in-house censorship; Sega Visions managed to survive for five years. That’s an incredible feat for propaganda, more so when you take into consideration how Sega never bothered to let the publication attain its full potential. Had Harris and Nilsen been given full creative control from the get-go, Sega Visions could have been a true contender.

Perhaps the saddest part is that despite the questionable corporate decisions made by an increasingly out-of-touch Japanese management, despite the constant comparisons to Nintendo Power, and in spite of all the in-house censorship; Sega Visions managed to survive for five years. That’s an incredible feat for propaganda, more so when you take into consideration how Sega never bothered to let the publication attain its full potential. Had Harris and Nilsen been given full creative control from the get-go, Sega Visions could have been a true contender.

In conclusion, we can essentially attribute Sega Visions’ troubles to three basic factors:

- The staff was denied full creative control. When someone upstairs tells you which games you’ll cover and what to say, creativity takes a nosedive and any credibility is lost. The fact that internally, Sega never viewed the magazine as anything more than an advertising gimmick hurt any chances it ever had, and the company’s attempts to publicly pass it off as a real magazine were both confusing and insulting to readers. Also, the denial of publishing anything negative at all about any of the games covered was a creative straightjacket for those who actually had to do the writing. All of this was compounded by a flimsy release schedule, and it was sometimes difficult to maintain the quarterly commitment to subscribers.

- The magazine was moved across the country. It may not seem like much at first glance, but when you uproot a publication and move it to the other side of the country, replacing virtually everyone involved, the quality is most definitely going to suffer. The staff change occurred at a critical time, when Sega was experiencing difficulties with the Sega CD and Game Gear, and both were heavily pushed by Visions at the expense of more worthy titles like Ristar and Gunstar Heroes (the latter of which got a paltry two pages in a single issue).

- It never had the full support of Sega. Even with management dictating what would be covered, no special stories or exclusives were given. How other news outlets could be privy to a story before the in-house publication is mind boggling. If any magazine should have been first to report everything Sega, it should have been Sega Visions. The very company in charge put it at a severe disadvantage and relegated it to “me too” status for big stories and news.

In the end, Sega Visions essentially outlived its usefulness, which is tragic, as the potential that was wasted was immense. It was par for the course in regards to Sega’s behavior during this period, and we can only wonder at what could have been. There is still a total of five years worth of great reading material, and if you can get past the rose-covered perspective of the writing, the historical significance of Sega Visions should not be underestimated.

Recent Comments