Michael Jackson has been called many things: The King of Pop, Entertainer of the Century, Eccentric – all of them attempting to define one of the most influential musical artists of all time. The man was seemingly everywhere during the 1980s and 1990s, either because of this incredible music and elaborate videos or due to his high-profile court cases. Jackson dominated the daily news cycle, and just about every element of his life was under scrutiny.

That is, except for one particular area. While it may now be common knowledge that Jackson was a big video gamer, it wasn’t necessarily the case 30 years ago. By the time the Dreamcast was sunset, Jackson had developed a long relationship with Sega, but his love of the company went back to his Bad days. Throughout his adult life, Jackson enjoyed Sega’s arcade games, eventually even owning several of them, including massive taikaen simulators like Galaxy Force II.

Jackson was reportedly drawn to Sega’s creativity and penchant for innovation, and one of the places he supposedly wanted to visit the most during his first trip to Japan was the company’s headquarters. There, he was impressed enough with OutRun’s music that he asked to meet the design team. Jackson was intrigued at the differences between his own music studio experiences and the kind of equipment found in Sega’s sound room. There were no musical instruments, and everyone was quietly working at their computers, headphones on. It was hard for the pop star to fathom how music could be created in such a fashion. Sega’s cutting-edge technology amazed Jackson, who, as an artist, always looked to push the boundaries of his craft and wow his fans. Though he was a gamer, he never thought video game technology was so advanced.

Jackson was reportedly drawn to Sega’s creativity and penchant for innovation, and one of the places he supposedly wanted to visit the most during his first trip to Japan was the company’s headquarters. There, he was impressed enough with OutRun’s music that he asked to meet the design team. Jackson was intrigued at the differences between his own music studio experiences and the kind of equipment found in Sega’s sound room. There were no musical instruments, and everyone was quietly working at their computers, headphones on. It was hard for the pop star to fathom how music could be created in such a fashion. Sega’s cutting-edge technology amazed Jackson, who, as an artist, always looked to push the boundaries of his craft and wow his fans. Though he was a gamer, he never thought video game technology was so advanced.

Hisashi Suzuki was the head of Sega’s R&D department and among the first employees to meet the famous singer when he visited. Suzuki didn’t listen to Jackson’s music but was aware of his status and made the effort to familiarize himself with the the star’s work before he visited Sega’s home offices. Suzuki was quite humble in his presence. “I’m not really a fan, so I don’t need any autographs,” he reportedly told Jackson, who was so impressed by his demeanor that the two became friends. Suzuki was completely honest about not being familiar with Jackson’s music, reportedly even refusing to take a signed jacket home. “I just can’t keep it for myself,” he admitted and left the jacket at Sega. It’s reportedly still stored there to this day, long after Suzuki retired.

Shooting for the Moon

Video game design can be a stressful job. Developers often sleep under their desks and fuel themselves with energy drinks and fast food to maintain their tight schedules. At Sega of Japan, things were equally exhausting. To promote socialization and offer a bit of respite from all the mayhem, the company had a smoking room on the seventh floor of Building Two of its Tokyo head office. It was there that Moonwalker had its – pardon the pun – Genesis.

Roppyaku Tsurumi went to that room often to enjoy a cigarette. A recent Sega hire, he came to Sega in 1989 almost by mistake. He got into video games as a hobby while in college, writing for the magazine Beep!. That April, he was assigned to cover Sega’s new System 24 arcade board and spoke to Sega’s hardware guru, Hideki Sato. The two men got along well, and their conversation eventually turned to Tsurumi’s job prospects. He was considering applying to Namco and mentioned Sega as a possible option. Hideki recognized the young man’s potential and immediately called in a human resources representative. Tsurumi was offered a job on the spot and trained in programming and writing design documents. He even spent time polishing the wood frame of Sega’s World Derby medal game in the company factory (where he reportedly found a box filled with copies of Tetris for the Mega Drive). His first job at Sega was as a hardware programmer, but he really wanted to make game software. Tsurumi was then transferred to Sega’s R&D 2 Department, under Yoji Iishi, a man who knew a thing or two about making games. Iishi directed Sega hits like Fantasy Zone, Hang-On, and OutRun, the latter two alongside another Sega legend, Yu Suzuki. He had worked with many of Sega’s elite alumni, including Noriyoshi Ohba (Revenge of Shinobi, Streets of Rage), and he had a keen eye for identifying unique game concepts.

Tsurumi was in that smoking room one day, relishing the few minutes of peace he could find with a cigarette and some quick conversation with colleagues. One day, Iishi came into the room and suddenly asked him if he would be interested in making a game based on Michael Jackson. The question took Tsurumi by surprise; he knew little about Jackson and his music. “All I knew was that he was an artist who was a really good dancer and a super famous person who has been active since he was a child,” he recalled in a 2024 interview. Tsurumi had only seen Jackson’s “Thriller” video and wasn’t really a fan, so he responded somewhat ambiguously. That answer was good enough for Iishi to assign him to plan the arcade version of Moonwalker.

Courting the King

Meanwhile, the head of Sega’s worldwide consumer products, Dai Sakurai, informed then-Sega of America Marketing Director, Al Nilsen, about the agreement for the development of both an arcade and Genesis title. Nilsen was also told that he would be the liaison between the company and the superstar. His first task would be to meet with Jackson and present him with Sega’s game designs for his approval.

The news came with almost no warning, just after five o’clock in the evening. Sakurai and Nilsen were scheduled to depart at nine a.m. the next morning, leaving little time to prepare. Nilsen hadn’t seen the designs, but Sakurai at least had examples of how Moonwalker looked animated. He had game sheets, but they lacked any actual description of the design. Not sure how to sell a game he knew nothing about, Nilsen had Sakurai call the development teams for both versions in Japan so he could orient himself, with Sakurai hastily translating as they spoke for almost five hours. The scant few game sheets that Sakurai had of R&D 2’s designs were by no means representative of the entirety of the project, but they would have to do. Nilsen took notes and eventually had enough material to make his presentation, though he didn’t meet Jackson right away. He was instead taken to see the pop star’s legal team, where he spent an hour justifying Sega’s pitch for the two games. Afterward, they were instructed to return to their hotel and wait for Jackson’s call. Frustrated, they went back to their room and ordered room service while they waited. A few hours later, the call came, and Nilsen and Sakurai were told that a car would be waiting for them downstairs in 15 minutes.

The meeting was to take place at Jackson’s studio and was supposed to last for no more than 20 minutes. As Nilsen and Sakurai arrived, they were stunned to see the musician come out to greet them personally. Apparently, he had ditched his lawyers back at the studio so he could greet his visitors in a more friendly fashion. He was also excited to see that Nilsen had brought him a new Sega Genesis console as a gift and even commented about how much he loved the Altered Beast arcade game. Accepting the boxed console made Jackson the first person in the U.S. to own a Genesis.

The pair chatted as they returned to the studio, where they had a pleasant meeting, despite the ever-hovering cadre of lawyers. Jackson and Nilsen sat on the floor, and the Gloved One listened intently and asked questions as the Sega executive showed him the images and design information he had brought. No one else got involved, and what was supposed to be a 20-minute appointment went on for almost two hours. The encounter not only earned Jackson’s blessing and involvement but was the start of a close relationship between Jackson and Nilsen. The lawyers and agents were excluded from subsequent meetings over the next year at Jackson’s LA studio and at Neverland Ranch.

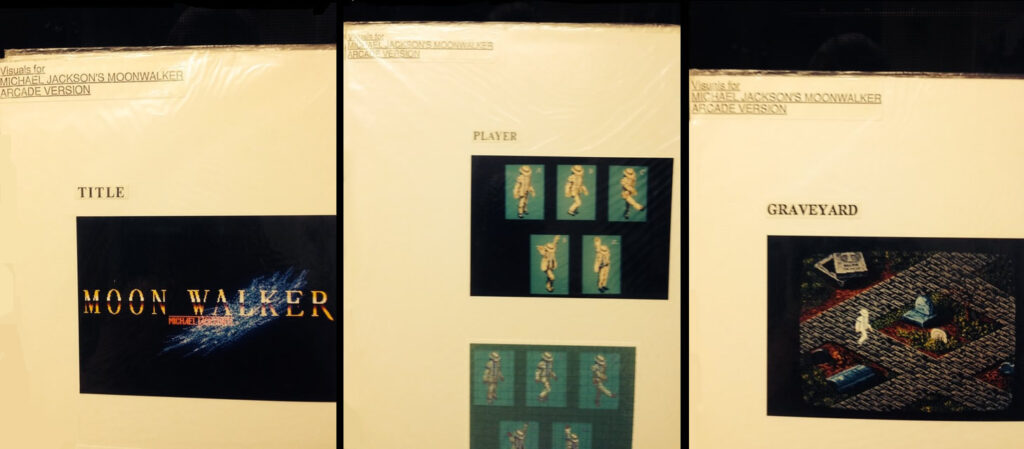

According to Tsurumi, the idea for a game featuring Jackson originated at Sega’s American branch. In a 2019 interview with the website Denfamicogamer, Tsurumi mentioned that SOA hoped to do something with Jackson, likely as part of its campaign to sign major stars to endorse its line of 16-bit software. “They proposed the idea of making a worldwide game using his IP, and that suggestion came to Japan. The department head, Ishii-san, who received this proposal, started asking the planners for ideas,” he recalled. Tsurumi also alleged that Sega of America had signed the contract to make both Moonwalker titles with Jackson’s representatives but without the artist’s knowledge. He contended that Jackson’s manager would normally have reviewed the contract and approved, but for some reason, this didn’t happen. “Since that kind of negotiation leading up to the contract signing didn’t happen, we had to create things like image boards and materials that clearly conveyed the game’s sequence, in line with the contract,” Tsurumi said. “It was quite different from the conventional way of developing games, so even when I asked people around me in Lab One, no one really knew what to do.”

Tsurumi’s allegations have been disputed by former Sega of America President Michael Katz, who clarified to the author that the license was procured in Japan before he even arrived, and by Nilsen, who recalled that a deal was reached between Sega of Japan and Jackson’s agent in the summer of 1989. Nilsen met with Jackson to explain the game concepts for both versions of Moonwalker and get his approval so that Sega of Japan could start development, and the initial meeting he and Sakurai had with Jackson’s lawyers wasn’t about negotiating. “My impression was that the contract had already been signed. I never saw a copy of the contract,” he told the author. Additionally, several contemporaneous industry publications indicated that it was Jackson who approached Sega about creating a game that would “capture his stage presence,” including arcade journal RePlay, which reported that Jackson proposed collaborating with Sega while on tour in Japan in the spring of 1989 (it was most likely the previous December, which was not only when the artist was in the country on tour but also when he was confirmed to have visited Sega’s headquarters). Regardless of when and how the partnership started, it wasn’t surprising that Sega agreed, given the history between the two.

Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’

The concepts Nilsen brought to his meeting with Jackson were actually the work of two different creative teams. Often, Sega did its arcade games first and then followed them with home ports but given that Moonwalker shared the same license and would have input from the artist himself, both versions of the game were done simultaneously. They shared roughly the same development milestones and followed the same design process.

Being new to game development and Sega’s way of doing things, Tsurumi was a bit overwhelmed, but thankfully, he wasn’t going to start development from scratch. Yutaka Sugano, the creator of the 1987 arcade hit Shinobi, had already presented a design pitch at Sega. Sugano had composed a single-page proposal that emphasized Jackson’s dancing. The game would have been played from an isometric perspective with a trackball, an unorthodox control scheme typical of Sugano’s design style (he originally designed Shinobi to be played with a shuriken-shaped controller).

Tsurumi wasn’t the only rookie on the project. Most of the members of the Moonwalker arcade team were inexperienced, except the designer, and he only had a mere two previous projects under his belt. Moonwalker was the first title for Programmer Sohey Yamamoto, who had also arrived at Sega in 1989. He planned on being an arcade cabinet engineer but soon found himself working with software. Both of the game’s artists were equally green. Artist Yoshiaki Aoki had only just been hired, and Moonwalker was his first assignment. The other artist, Taku Makino, had at least worked on a few games, having done art for Tetris (1988) and ESWAT (1989). His work had a certain… trend to it, namely that of primates. Makino drew the monkey that appeared on the “GAME OVER” screen in the arcade version of Tetris, as well as the gorilla in ESWAT. Fittingly, he would illustrate Bubbles the Monkey in Moonwalker. A year later, he would create the first physical model of Sonic the Hedgehog used as a reference for animating the character for his debut title. The team’s situation wasn’t unusual. Rather than start with small projects, many of Sega’s most seasoned designers, producers, programmers, and planners cut their teeth on major titles early in their careers, learning the trade from the company’s veteran staff. The company was at the top of its game in both the arcade and console markets, and game production costs were still low. This environment made it less risky for Sega to offer big chances to new hires. It was a philosophy the developer later tried to recreate with its Sega Technical Institute at its American branch, though to much lesser success.

Even so, there was some concern about how Moonwalker would turn out. The arcade team’s lack of experience made development tough early on, and there was constant concern about whether it was up to the job. Tsurumi had more pressure than most since he was the project’s planner. The console Moonwalker crew was more experienced, which greatly worried those working on the arcade version. “Nowadays, it’s common sense to have a dedicated planner/designer and an experienced director on projects,” Tsurumi recalled, “but back then there wasn’t any separation between those two roles. So, it was very common for the planner/design to just be a jack of all trades.” Thankfully, veteran developers eventually joined him, and the game gradually took shape towards the middle of development. The weight of the project was apparent to everyone involved; they didn’t want to disappoint the most popular entertainer in the world, and Hisashi Suzuki had made it clear to them that Jackson wanted to do something innovative. “Don’t just make an ordinary game with Michael’s name on it,” he warned. “He will demand something completely new.”

Tsurumi’s role as planner often left him perplexed about how to proceed. What would he do with a game designed around dancing, and how could it work when played from an isometric perspective? He consulted his direct superior, Hisao Oguchi, who referred him to Motoshige Hokoyama, who was supervising the Mega Drive version of Shadow Dancer. With everyone working long hours and even sleeping at the office, the supervisor was unable to assist Tsurumi, so the young planner had to find his own way. Thankfully, a conversation with Sugano about the game Crack Down helped put his mind at ease. The elder designer told him not to overthink the perspective and instead concentrate on the gameplay. If Shinobi’s core gameplay could work in Crack Down with an overhead perspective, it could work with an isometric one.

Tsurumi quickly learned from the other arcade titles under development at Sega of Japan. The company allowed department members to play them after they reached a certain point in development, so Tsurumi and his group played Shadow Dancer and Bonanza Bros. every day. Tsurumi also spent many hours working through Uchida’s Alien Storm. He was a big fan of Golden Axe and played the cabinet in Sega’s lobby constantly. With time, he could see how each of these games shared a similar gameplay design, despite their different view perspectives and styles. Making this connection gave Tsurumi the confidence and direction he needed for Moonwalker.

Tsurumi quickly learned from the other arcade titles under development at Sega of Japan. The company allowed department members to play them after they reached a certain point in development, so Tsurumi and his group played Shadow Dancer and Bonanza Bros. every day. Tsurumi also spent many hours working through Uchida’s Alien Storm. He was a big fan of Golden Axe and played the cabinet in Sega’s lobby constantly. With time, he could see how each of these games shared a similar gameplay design, despite their different view perspectives and styles. Making this connection gave Tsurumi the confidence and direction he needed for Moonwalker.

Interestingly, Tsurumi didn’t think that Sega had much faith in his ability at the time, given his lack of experience, nor was there an overdose of confidence in the game’s potential. “I think I was looked down upon very little within the company, with people just thinking, ‘I don’t know if the Michael Jackson game will be a hit, but let’s put some young people in charge of the project, and if it turns out to be a success, that’s good.'” He wasn’t even assigned a translator for his interactions with Jackson, which caused problems with trying to maintain the schedule set by Sega of America. All communications were in English, and Tsurumi only had the basic skills he learned in school. He wasn’t proficient in business English and found reading contracts difficult. Sega of America would ask him to create an image board or provide a build of the latest version by specific dates, and he had to determine on his own what he should send. He had only a fax machine at his disposal, and it wasn’t even in the same building. Tsurumi had to walk over to the Overseas Consumer Business Division to use it. Data for both versions of Moonwalker were sent together to speed things up. Tsurumi eventually learned to manage his communications with Sega’s American arm, and as the arcade game progressed, he sent updates to Jackson at each milestone, complete with concept sheets and even videos. The language barrier was always an issue, and Tsurumi used a dictionary to complement his limited English skills.

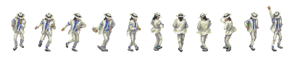

Tsurumi was eager to see the game approved by Sega, so the team worked diligently to please both its superiors and Jackson himself. Sega had guidelines for developing an intellectual property, and most designers usually played it safe, sticking to them to ensure that their projects would be approved. However, Jackson wasn’t content to sit on the sidelines and be told what was happening, and he personally went over the image boards and latest builds. Each time he received an update, he would send a personal response through his representative that was polite and full of feedback. The star made suggestions rather than demands, and his faxed responses would typically start with, “Mr. Jackson says…” and include recommendations that took into consideration the opinion of the development team, something that surprised Tsurumi. Jackson was reportedly always respectful of the design team’s skill and talent. At one point, The group decided to make the game playable by three players at once, but there was an issue with how each character sprite would be displayed. As Moonwalker was based on the classic “Smooth Criminal” portion of the film, Jackson was adamant that his white suit be used by the player character. Tsurumi mentioned to him that having three players with the same color would be confusing, and he suggested that the other two use red and black. Tsurumi was worried that Jackson wouldn’t go for it, but to his surprise, he quickly agreed. The impression that Tsurumi and the others had was that the King of Pop didn’t want his ego to overshadow Moonwalker’s design.

Another example concerned a mech-like vehicle driven by one of Mr. Big’s thugs. The foe never appeared in the film and was an original creation for the arcade game. It attacked by the driver moving a piston back and forth between its legs. As its design neared completion, there was concern that it was perhaps too scary for younger players. The mecha’s data was already in the ROM, so rather than eliminate it completely, the team tweaked its look to make it more appealing. Tsurumi was hesitant to ask Jackson about it, but he was in favor of the mecha being included in the final game as it was.

Such actions were a common theme by the star, and team members were reportedly impressed that an artist of his stature would be so humble. Jackson’s recommendations often focused on style and ways to make the game more visually appealing. “Every time I sent out materials, I got feedback like, ‘Mr. Jackson wanted the bullet holes left by the machine gun hitting the wall to form an ‘M,’ so, if possible, please include that,'” Tsurumi said. Jackson also suggested that his character not kill anyone except for the last boss, and he would instead “purify” enemies and blow them off-screen. Not even the dogs could be killed (they could indeed be made to dance, though), so Tsurumi gave the dogs armor that would disappear when hit, indicating that they were under evil influence that had now been purged. Jackson also wanted to transform into a spaceship at the end, just as he did in the film.

Obviously, Jackson was also heavily involved in Moonwalker’s sound design. Because of the unique nature of his relationship with Sega, the company was able to get a license for his music and voice for only 5,000 yen, a fraction of what it would normally cost to collaborate with such a hugely popular entertainer. The design team asked that he record voice work, between 40 and 50 phrases in all. The members were amazed to receive a 60-minute audio cassette filled with Jackson’s trademark sounds (one can imagine what it must have been like to hear an hour’s worth of “Foo!,” “Dah!,” “Pa-oh!,” “Acho!,” and “Ao!”) There were so many sounds included that the team was able to have some fun using them. For example, Tsurumi used Jackon’s famous “HOO, HOO!” for when a coin was inserted. “I thought, ‘It would be so much fun if Michael’s voice ringed out when you put a coin in at an arcade,’ so I got a little mischievous and asked the sound manager at the time, ‘Please make the volume as loud as possible just for this voice that plays when a coin is inserted.'” Lamentably, the cassette has been lost to time.

Both the arcade and console creative teams operated with a common premise that followed the movie: Jackson would fight the vile drug kingpin, Mr. Big, and his thugs to rescue his child friends. How the pop star executed this mission is where the two games differed. In the Genesis game, the action took place from a 2D side-scrolling perspective as Jackson moved through different stages to rescue a specific number of children who were hidden (they were all Katie, the young girl. The other two orphaned children, Sean and Zeke, were nowhere to be found). Each stage featured one of Jackson’s hit songs, including “Billie Jean,” “Beat It,” “Bad,” “Another Part of Me,” and “Smooth Criminal” (neither version of Moonwalker included “Thriller” because of copyright issues since Jackson didn’t compose the song), and although the first run of Genesis cartridge did include a segment of it as the dance theme for the graveyard stage, it was subsequently removed in later revisions. Just as in the film, Jackson could transform into a robot and deal massive damage to his foes, and he used a special attack to make all onscreen enemies dance. Overall, the home version followed the plot closely, albeit with a few changes.

In comparison, the arcade release seemed a bit more complete. It retained the same basic elements of its Genesis cousin across its five zones (13 stages overall), but it played from an isometric perspective. All three children were present, and Jackson’s attacks were now electric rather than the magic sparkles he shot in the home version. The attack could also be charged, resulting in a larger area of effect. The dance attack was present but looked much better, with more fluid animation and a cool spotlight that shined down on the star as he led his foes to their musical doom. He could also turn into a robot here, but instead of flying all over the screen, he simply became a beefed-up tank of a creature that walked around and decimated everything in his path. Additionally, the coin-op game sported a larger variety of enemies and had more of them onscreen at once, more boss battles, and it unveiled the plot through simple comic-like cut scenes between each stage. These enhancements stemmed from Sega’s use of its System 18 arcade system. The hardware was brand new but was essentially an more powerful version of its previous System 16 architecture, adding better sound, more tile layers, and a few graphical enhancements.

All The World Is His Stage

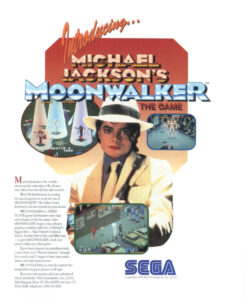

Sega debuted an early build of both the Genesis and arcade versions of Moonwalker at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas in January 1990 and boasted about how Jackson had refused a tie-in deal with Nintendo a few years earlier but now chose to sign with Sega. Sega of America announced the launch date for the Genesis cartridge the day before the Moonwalker film arrived on home video and expected the coin-op to debut alongside its console game in July 1990, but Sega Enterprises staffers refuted the prediction and were unable to provide an exact release date. It did present a more complete version that spring at the American Amusement Machine Association (AAMA) Expo in Mexico City, Mexico. The machine was sold as both a dedicated cabinet, meaning that it couldn’t be converted into another game by swapping out the PCB and control panel, and as a conversion kit. For a major release about a star of such renown, the cabinet design itself was quite subdued, with three stations for play – left, right, and center – and bearing only a standard marquee and side art. Perhaps its most distinguishing feature was the header placed atop the marquee. The prototype header was different from the one that finally shipped and only showed Jackson doing his famous pose, right arm stretched upward as he looked down at the floor. The final version had an image of the star in his white suit next to the phrase “FIRST THE MOVIE AND NOW SEGA BRINGS YOU THE VIDEO GAME.” It was much larger and eye-catching than the prototype.

Sega debuted an early build of both the Genesis and arcade versions of Moonwalker at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas in January 1990 and boasted about how Jackson had refused a tie-in deal with Nintendo a few years earlier but now chose to sign with Sega. Sega of America announced the launch date for the Genesis cartridge the day before the Moonwalker film arrived on home video and expected the coin-op to debut alongside its console game in July 1990, but Sega Enterprises staffers refuted the prediction and were unable to provide an exact release date. It did present a more complete version that spring at the American Amusement Machine Association (AAMA) Expo in Mexico City, Mexico. The machine was sold as both a dedicated cabinet, meaning that it couldn’t be converted into another game by swapping out the PCB and control panel, and as a conversion kit. For a major release about a star of such renown, the cabinet design itself was quite subdued, with three stations for play – left, right, and center – and bearing only a standard marquee and side art. Perhaps its most distinguishing feature was the header placed atop the marquee. The prototype header was different from the one that finally shipped and only showed Jackson doing his famous pose, right arm stretched upward as he looked down at the floor. The final version had an image of the star in his white suit next to the phrase “FIRST THE MOVIE AND NOW SEGA BRINGS YOU THE VIDEO GAME.” It was much larger and eye-catching than the prototype.

Sega finally premiered the complete Moonwalker in the U.S. in August 1990 at its distributor meeting at the Silverado Country Club in California’s Napa Valley. Having just launched that very month, it was the highlight of Sega’s presentation and was an instant hit with distributors. One of California’s biggest coin-op distributors, C.A. Robinson & Co., held an event that same month where over 600 people played the machine and orders were taken. The distributor sold its entire Moonwalker stock that afternoon. The game was just as popular with arcade goers. Moonwalker fever caught on in arcades in both Japan and the U.S. As soon as it was released, the danced its way into U.S. arcades in August 1990. It was a major seller for Sega, debuting at #9 on Game Machine magazine’s top 25 hit list and remaining in the top ten for months. Moonwalker was equally successful overseas, ranking high on the charts across North America.

You Are Not Alone (In Hoping for a Port)

While many Genesis owners wondered if the arcade Moonwalker would ever make its way home to the Genesis or Sega CD, it was unlikely that a home port would ever have happened. Sega had only negotiated with Jackson for Genesis and arcade titles, and the cartridge release made a console port a non-starter. So, adding a Sega CD port would have meant obtaining an entirely new license. Obtaining one wouldn’t have been on Sega’s radar because by the time the CD-ROM expansion arrived in 1992, Moonwalker was already two years old. A lot had changed within the company by then, including Sega of America’s management and the introduction of a speedy blue hedgehog. Jackson was not the priority anymore.

Likewise, the pop star himself had evolved since Moonwalker’s debut. He released his Dangerous album a year after the games appeared, sporting a grittier sound and a change in artistic direction. He would likely have been as far past Moonwalker by this stage in his career as Sega, so it would make little sense to bring the game back. As Sega’s consoles became more advanced, Moonwalker kept getting further in the rear-view mirror. The artist’s death in 2009 most likely closed the book on any chance of a licensed port of either version of the game.

Moreover, the legal troubles that plagued Jackson throughout the 1990s would preclude any further collaboration between him and Sega, as the game maker quietly cut ties with him around the time of Sonic 3’s release (as seen in our “Sega Legends: Michael Jackson” article). The 1993 motion simulator attraction that Sega developed for its larger game centers, the AS-1, included Jackson in a game called Scramble Training, but his likeness and name were removed when news of his sexual abuse allegations broke. It would take years for their relationship to return to a stage warranting collaboration, and Jackson wouldn’t reappear in a Sega game until a cameo in 1999’s Space Channel 5 on the Dreamcast. According to the Space Channel 5 Gyun Gyun book, that appearance was supposedly tied to Moonwalker in that Jackson is the same person from that game, only 500 years older. It was never explained how the two titles were connected, and that was probably because Jackson got involved in Space Channel 5 late in its development, so his role was small. It wasn’t the Moonwalker port or sequel fans wanted, but it’s still interesting to think that Sega did manage to tie the two games together.

Still A Thriller

While we never got a home port of Moonwalker, the miracle of emulation at least provides a chance for interested players to find means by which to play it. Perhaps someday, Sega will find interest in bringing the game home (maybe a compilation of all versions?) and endeavor to obtain a license from Jackson’s estate to make it happen. It may sound like a longshot, but Sega worked with Disney some years back to provide not just a port, but a full 3D remake of Castle of Illusion. There was precedent for such a move. In March 2007, Ubisoft worked out its licensing issues with Konami to bring the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles arcade game to Xbox Live Arcade. As I said, it’s a longshot, but even a small chance is better than none.

While we never got a home port of Moonwalker, the miracle of emulation at least provides a chance for interested players to find means by which to play it. Perhaps someday, Sega will find interest in bringing the game home (maybe a compilation of all versions?) and endeavor to obtain a license from Jackson’s estate to make it happen. It may sound like a longshot, but Sega worked with Disney some years back to provide not just a port, but a full 3D remake of Castle of Illusion. There was precedent for such a move. In March 2007, Ubisoft worked out its licensing issues with Konami to bring the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles arcade game to Xbox Live Arcade. As I said, it’s a longshot, but even a small chance is better than none.

In the end, all we can do is enjoy the game for what it is: a wonderous pairing of two of the biggest heavyweights of their respective industries. Moonwalker is a project the likes of which we won’t ever see again, and while some may consider it the ridiculous vanity project of an eccentric celebrity, I think most of us welcome Sega’s willingness to make such a unique concept happen. It may not be as impressive today, but Moonwalker is a game that everyone should experience at least once.

Sources

- “C.A. Robinson Celebrates ‘Sega Day’ with Moonwalker.” RePlay, September 1990.

- “Cover Story.” RePlay, September 1990.

- “Game Machine’s Best Hit Games 25.” Game Machine, September 15, 1990.

- Garcia Ruiz, Luis. “[10 years since Michael Jackson’s death] Looking Back at the King of Pop’s Interactions with the Sega Staff Who Supported Him and Poured His Soul into the Video Game ‘Moonwalker.'” June 25, 2019.

- Horowitz, Ken. Playing at the Next Level: A History of American Sega Games. (Jefferson: McFarland, 2016).

- —. The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games. (Jefferson: McFarland, 2016).

- Katz, Michael. LinkedIn direct message to author, March 21, 2025.

- Kurokawa, Fumio. “Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker: The Inside Story Behind Its Development.” Shueisha Online. June 25, 2024.

- “Moonwalking through the Vineyards.” Play Meter, September 1990.

- “Moonwalking with Sega: Hot New 3-Player Video Coming Soon.” RePlay, August 1990.

- Nilsen, Al. X ,direct message to author, March 25, 2025.

- Ohshima, Naoto (@NaotOhshima). “Mr. Makino made Sonic the first time in 3D. It is a picture at that time. He is Sega’s greatest artist!” X, March 29, 2017, 8:13pm.

- “Powerhouse! Home Games Look Robust at Winter CES Show; ‘Coin-Op Must Get on Track Fast,’ Observers Say.” RePlay, February 1990.

- Sakazaki Mayumi, Nina. Memories of Michael Jackson. (Tokyo: Poplar Publishing Co., 2010).

- “SEGA AGES Columns II: Staff Reflections.” December 19, 2019. YouTube, 5:22.

- Rekkasha, ed. Space Channel Gyun Gyun Book. Futabasha Co., Ltd., 2000.

- Tsurumi, Roppyaku. “Astro City Mini and Game Design (Part 1).” One Million Power, February 5, 2021.

- —. “Astro City Mini and Game Design (Part 2).” One Million Power, February 12, 2021.

Pingback: Sega’s One-Sided Story – The History of How We Play