Genesis Does… Licensing

The practice of attaching big name licenses to existing games that began on the Master System continued with the Genesis. At the time of the new 16-bit machine’s release, newly-installed Sega of America (SOA) president Michael Katz knew that he could not compete with the virtual monopoly Nintendo had on arcade conversions. With few publishers able to release their games on the Genesis, Sega could not count on the hottest coin-op titles beyond those it published itself, which were limited in number. In order to make the Genesis stand out more among the competition, Katz took a three-pronged approach: First, he would boost the U.S. side of game development. Second, he would step up efforts to secure licenses for the most popular athletes and personalities he could. Third, Sega would take the fight to Nintendo itself.

To accomplish this, Katz hashed out an agreement with his Japanese superiors that would let the two branches focus on the game genres at which they were best. If Katz were to ever achieve his goal of attracting major athletes for games that could compete successfully against Nintendo, he would need full control over the development of the software involved. The tactic of licensing existing Japanese sports titles had been a regular practice on the Genesis since its launch, with games like Arnold Palmer Golf, Tommy Lasorda Baseball and Pat Riley Basketball already on store shelves, but none of them offered the level of quality needed to put Sega ahead of the competition. “We wanted to start an internal development department at Sega U.S.,” he told Sega-16 via phone call, “and it made sense that the U.S. would develop sports games and several other categories that had an American bent, and Sega Japan would develop character-based/cartoon/action/arcade-type games, which was their area of expertise, along with a few other categories.”

Sega of Japan, while still reluctant to pay out the amount of money needed to secure major licenses, agreed that it would be best if its American arm handled sports game development. “The Japanese had no experience with sports games.” Katz recalls. “They did know action games; hence Sonic was developed in Japan.” This gave Katz a great deal of freedom towards filling in areas of the fledgling Genesis library that Japan could not cover, but he still needed to convince his Japanese superiors that it was worth going after major sports stars. He felt that if Sega of America could convince consumers that the best sports games were found on Sega’s 16-bit machine, Japan would finally see the revenue potential they could offer.

Katz began the process by hiring Ken Balthaser as his vice president of product development. Balthaser, who had experience with managing internal software development at game companies like Exidy and Atari, had the unenviable task of creating an American publishing arm for Sega. However, instead of incurring the massive expense of hiring entire development teams to work internally for Sega, he chose a more effective route. Since managing massive teams would eat up valuable development time, Balthaser considered it more prudent to hire external teams that would work under the guidance of Sega producers.

“When a project development arm grows that large that quickly,” he told Sega-16 in our 2006 interview, “you spend all your time managing that rather than developing games, so I opted to not do in-house development but rather go outside. So instead of hiring programmers and designers, I hired therefore, people to support that vision. I hired producers, using contacts of game developers — people I had known back from my days at Atari — and we brought them under contract to manage those who were developing games for us. So, that’s how we did it. We had a very good group of producers, and we had development going on all over the place, in Hungary, England, France, and a bunch of other places. That’s how we began development here, and I think very quickly we were able to get our first products out the door.”

Though no one knew it at the time, the decision to let Sega of America handle sports development independently of Japan would be a major catalyst in the company’s overall success over the next half decade. By breaking free of the often-used rule of simply localizing Japanese games, American executives were able to focus on what their audience specifically wanted. Simply placing a popular sports name on a localized Japanese sports title hadn’t produced the consistency of gameplay quality that Katz wanted, and development would have to expand to create deeper and more realistic gaming experiences. The slow transition from this situation affected American-made titles early on, since sports titles were each handled by different external teams. “We always tried to make every sports game as great as possible (better gameplay, better graphics, animation, more realism, better sound, etc.),” he explained, “but this was influenced by how much time we had, how expensive development was and the quality/talent of the developers. In some cases the graphics were better than the gameplay and vice versa.”

Though no one knew it at the time, the decision to let Sega of America handle sports development independently of Japan would be a major catalyst in the company’s overall success over the next half decade. By breaking free of the often-used rule of simply localizing Japanese games, American executives were able to focus on what their audience specifically wanted. Simply placing a popular sports name on a localized Japanese sports title hadn’t produced the consistency of gameplay quality that Katz wanted, and development would have to expand to create deeper and more realistic gaming experiences. The slow transition from this situation affected American-made titles early on, since sports titles were each handled by different external teams. “We always tried to make every sports game as great as possible (better gameplay, better graphics, animation, more realism, better sound, etc.),” he explained, “but this was influenced by how much time we had, how expensive development was and the quality/talent of the developers. In some cases the graphics were better than the gameplay and vice versa.”

Even with these constantly changing factors, Sega of America’s sports games managed to be successful more often than not. The marketing impact of the license at this early stage cannot be underestimated, and while Katz was aware of how big names attract customers, he was also clear that the games had to be worth playing. The license was designed to encourage gamers to buy a Genesis and a few cartridges, but good gameplay and high replay value would maintain their interest and keep them coming back. A reputation built on quality would be one of Sega’s major weapons for counteracting Nintendo’s overwhelming retail presence.

Of course, the primary goal was to get gamers to buy a Genesis, and having the hottest athletes endorse the machine’s sports library was a major publicity coup. All these celebrities cost money though, and Japan was worried that the gains weren’t worth the asking price. However, even with the high cost of licensing overall, many of the athletes Sega sought out weren’t as expensive as Japan may have thought. Some, such as former boxing heavyweight champion James “Buster” Douglas, were well within the company’s marketing budget because athletes for less prominent sports, like boxing, didn’t command the same type of licensing muscle that NBA, NFL and MLB players did. This fact compensated somewhat for the embarrassment Sega experienced when Douglas lost his title during his first defense. Fortunately, Douglas’ short reign still managed to accomplish its marketing goal, even with its unexpected end. Fueled by this success, Katz and his team continued to seek out the top names in each sport, determined to convince Sega of Japan of the policy’s viability.

Japan’s reluctance to sign expensive sports licenses almost caused Sega to lose Joe Montana to Nintendo, and it was most likely Katz’s insistence that finally brought the famed quarterback over to Sega’s side. Katz wanted the biggest name around at the time, and he needed the right game – a western-made game – to get him. He had secured a deal with Mediagenic (formally and presently known as Activision), and Montana was crucial to getting Sega an attractive football game for the coveted holiday season. Both Nintendo and Sega were locked in a bidding war to obtain Joe Cool’s name, and although Nintendo ended up offering more money, Montana opted instead to sign with Sega. Contrasting with the high stress levels felt by Sega executives about the signing, Montana was his typically laid-back self about the entire affair, accepting his first million-dollar licensing check at the official signing party in jeans and a t-shirt and with a simple thanks and a grin, then folding it and placing it in his back pocket as he stepped from the podium. Katz has often wondered if Montana remembered to remove the check before tossing those jeans in the hamper.

Despite the informality of the arrangement (as well as the roller coaster ride that was the development of Joe Montana Football), the result was a yearly franchise that directly competed with Electronic Arts’ Madden series for the next half-decade. The success of the game convinced Sega of Japan that there was a future in American-developed sports titles, and the branch was subsequently allowed great control over their creation and marketing. Sega of America took this new-found business capital and ran with it, eager to show Japan that it had been correct in turning the sports genre over to its subsidiary.

One of the first places Sega applied the sales momentum garnered from Joe Montana Football was the launch of its new portable game machine, the Game Gear, and it used the port of its new football hit as a graphical showcase for the new system. First made available in New York in late 1990 and then unrolled throughout the rest of the country, the Game Gear featured color graphics and a back-lit screen, but most importantly for Sega, it was built on the 8-bit Master System architecture. This made porting games from the Master System easy, and Sega had a large library of game engines from which to produce quick and easy ports. Former Sega Director of Marketing Bob Botch, who oversaw the Game Gear’s launch, explained to Sega-16 why this was so important to the portable’s early success. “We had a little bit of a plus with the Game Gear.” he detailed in a phone interview. “It was the same chip as the Master System, so we had a library of game engines to pick from. All we had to do was take the baseball, football or boxing engine and do some re-engineering, enhance the colors, etc. Sports were pretty big on the Master System, so we had a pretty big library to pick from.”

Out of all the Sega-made games available in the Game Gear’s initial library, the one that that received the most emphasis was the portable version of Joe Montana Football. As the Game Gear wasn’t as powerful as the 16-bit Genesis, the game had to be reworked in order to be playable on the smaller system. For this reason, the handheld version of Montana only features eight players on each side. Sega considered this release to be a key component of the Game Gear’s push at retail and even bundled the game with the machine as a pack-in title. This resulted in a major bump in sales, something sorely needed if the Game Gear was to ever have a chance of establishing a foothold against the much more popular Game Boy.

Unknown to most, this success almost never happened. Technical problems plagued the Gear-to-Gear connection that allowed two players to link their machines via cable, and playing against a friend – something most people consider to be a fundamental part of the sports genre – proved to be harder than anyone anticipated. Every time Sega programmers thought they had syncing issues worked out, another problem cropped up that sent them back to the drawing board. Eventually, this hurdle was overcome, allowing Game Gear owners to enjoy person-to-person match ups with their friends.

Though Joe Montana Football was a major success all around for Sega, relatively few other licenses were pursued for the Game Gear. Notwithstanding, licensing was a still a large part of the marketing strategy as far as the Genesis was concerned, and this philosophy continued even after Katz left Sega, as developers were contracted to make sports games that Sega would publish itself. The small groups would work externally with oversight from Sega, which would also handle the marketing and distribution chores. Developers like BlueSky Software, Ringler Studios, and ACME Interactive would all soon come on board to add to the growing Genesis sports library.

The first results of this new policy were seen in Alpine Studios’ Mario Lemieux Hockey (1991), which had the endorsement of the Pittsburgh Penguins star. In addition to obtaining the license, Sega included a limited edition hockey puck as a bonus (100 were actually hand-signed by Lemieux himself). Released in a large cardboard box, the whole affair was obviously soaked with marketing, but the product that was being so heavily promoted actually made an honest attempt to go beyond its packaging by offering detailed graphics and the ability to have players fight each other in grim detail. Ultimately, the high cost of marketing hampered what could have been a much more complete release by limiting its reflection of the actual sport. Mario Lemieux Hockey managed to produce a solid hockey experience, but it lacked real NHL players and teams. This put it at a severe disadvantage compared to EA’s NHL Hockey series, which included both major licenses. Sega would eventually overcome this hurdle with its own dedicated hockey series, NHL All-Star Hockey, on both the Genesis and the Saturn, but the first game didn’t arrive until the tail end of the 16-bit era, far too late to dull the impact of EA’s franchise.

The lack of authentic teams and players was not due to laziness on Sega’s part. In truth, few publishers had more than a single athlete’s name attached to their games until the early ’90s. Most still considered a celebrity endorsement enough to entice consumers, and Sega was no exception. With a small marketing budget and a distribution and retail base well behind that of Nintendo, it would have been far too expensive for Sega to seek out separate licenses for major leagues like the NFL and the player associations for each sport. Moreover, it was also cost prohibitive to pursue a league license for advertising, which is why athletes like Joe Montana and Mario Lemieux never wore their team uniforms in ads or commercials.

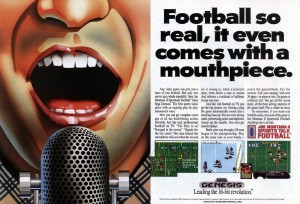

Content with the growing number of external teams now coming aboard to create sports titles and energized by the success of the first Joe Montana Football, Sega was able to put a much greater effort into creating an in-house sequel to what it hoped would become a signature sports franchise. 1991’s Joe Montana II: Sports Talk Football by BlueSky Software changed the game perspective and ramped up the visuals through weather effects and a zoom feature, but its greatest innovation was the new “sports talk” dynamic. This revolutionary new technology was the work of two companies, vocal reproduction company Electronic Speech Systems (ESS), the same company that had popularized the revolutionary synthetic speech technology found in video games such as the arcade classic Berserk and the Commodore 64 hit Impossible Mission, and Western Technologies, which specialized in game development tools and had designed the innovative Vectrex game console.

The process for recording and incorporating the speech was complex. First, Western created a list of words that would be used in the play-by-play commentary. This list was then sent to ESS for recording. Famed San Francisco announcer Lon Simmons was hired to provide the play-by-play, and his words were recorded, compressed and stored on a chip. Finally, the chip was sent to Western, where a script was developed around Simmons’ words.

While Western worked on the voice synthesis, BlueSky Software was busy working on the game itself, and getting the two halves to mesh seamlessly was extremely difficult. Code was sent between the two teams remotely, and this was very slow going, as megabytes of data had to be transmitted back and forth over 1200 baud modems. Working against the clock, BlueSky managed to bring everything together before its final deadline. Former Sega producer Scott Berfield explained to Sega-16 how hectic things really got at the end. “We fixed the last major bug (which happened because the two teams had indexed arrays differently) a few hours before the absolute drop dead deadline to ship to Japan, got a full test pass done and sent code to Japan pretty much at the last possible minute.” Thankfully, the game shipped on time, and Genesis owners everywhere got to sit wide-eyed while Lon Simmons called their favorite team’s games.

Contrary to popular myth, Simmons was not chosen because of his famed career as an announcer but instead for his low, monotone voice, which was easy to compress with ESS’s technology. Using the voice synthesis, programmer Jeff Forte invented a script format for the speech used in the second Montana game. Allen Maynard, the Western Technologies programmer who worked on Sports Talk Baseball, explained to Sega-16 via email how the processed worked. “You may think that a lot of dialogue was saved on the voice chip, but in reality, each word Lon Simmons said was stored only twice, one with a high inflection on the end and one with a low inflection on the end. This way, a word could be used at the beginning, middle, or the end of a sentence. The dialogue that you hear in the game used the words in a script that was saved on the cartridge.” Once recording was completed, Simmons approved each word personally, to ensure that the final audio was up to his broadcast standards.

At the time, such a large amount of speech was unheard of for a cartridge release, and the game was hailed as a technical marvel. Trip Hawkins even called it “true multi-media.” In reality, the fluidity of the commentary actually had little to do with compression and more to do with the length of the scripting. Maynard compiled a script that cycled the words randomly in order to avoid repetition. “What I did,” he told us, “was write a script that used the words in a dynamic environment which chose random sequences of phrases that were pieced together on the fly. This way you never knew which combination of words would be said. A single sentence could consist of dozens of combination of words written in a fashion that branched out very much like a tree. Imagine starting the sentence from the trunk of the tree, randomly taking branches left and right and finally winding up at the leaf. The path to the leaf was a complete sentence but only one of a dozen combinations.” Thus, depending on the length of the script Maynard wrote, numerical values like batting averages and scores could be changed with no delay.

At the time, such a large amount of speech was unheard of for a cartridge release, and the game was hailed as a technical marvel. Trip Hawkins even called it “true multi-media.” In reality, the fluidity of the commentary actually had little to do with compression and more to do with the length of the scripting. Maynard compiled a script that cycled the words randomly in order to avoid repetition. “What I did,” he told us, “was write a script that used the words in a dynamic environment which chose random sequences of phrases that were pieced together on the fly. This way you never knew which combination of words would be said. A single sentence could consist of dozens of combination of words written in a fashion that branched out very much like a tree. Imagine starting the sentence from the trunk of the tree, randomly taking branches left and right and finally winding up at the leaf. The path to the leaf was a complete sentence but only one of a dozen combinations.” Thus, depending on the length of the script Maynard wrote, numerical values like batting averages and scores could be changed with no delay.

The positive publicity the feature generated for Sega caused it to add the technology to its unfinished baseball title a localized version of the Japanese game Pro Yakyuu Super League ’91, which was in the final stages of development. Having grown up around the Los Angeles area, Maynard organized some of the phrases used to sound like famous MLB broadcasters of the time. There was little voice work that was actually new, however, and Sports Talk Baseball recycled parts of Simmons’ speech from Montana II but turned out to be a much more balanced and enjoyable experience, despite not having the same level of visual polish.

There would be further football games in the Sports Talk line all the way through the ’94 edition (the last to actually bear Montana’s name, though he still appeared on the cover the following year), and many thought that Sega would continue to expand it to other sports, but none ever materialized. In truth, none were ever planned. However, Simmons’ voice work would appear in a football game one more time in the 1994 U.S. exclusive College Football’s National Championship, which was essentially a low cost conversion of NFL ’94’s engine but with college teams and players. With development running behind schedule and little additional programming required to complete the product, BlueSky Software decided to maintain the Sports Talk commentary of the original game. It was eliminated for the sequel, which in turn used the space for added features, animations, and enhancements.

Beyond this unconventional, last minute inclusion, there would be no more Sports Talk sequels. The voice synthesis in these games was considered more of an added feature than the focal point for a franchise. Evidence of this can be seen in games like Greatest Heavyweights, one of the first major sellers for the Sega Sports line, which includes real speech but to a far lesser degree than the Sports Talk titles despite being released years later and on a more advanced game engine. There would be no more real-time commentary in Sega Sports games until World Series Baseball arrived on the Saturn in 1995. Sega instead decided to move away from gimmicks and major licenses and concentrate on producing the most accurate sports experiences possible on the Genesis and its add-ons.

The shift actually began before the Sports Talk series even ended. For instance, NFL Sports Talk ’93 Starring Joe Montana introduced a process called “digitized animation” where NFL player Marcus Wilson’s movements were captured and digitized. Sega even went as far as to allow Montana’s involvement to go beyond just a cover appearance. Both NFL ’93 and later ’94 featured new playbooks created by Oakland Raiders Offensive Coordinator Tom Walsh with input from Montana himself. This attention to detail was essential for convincing gamers that there was another major software contender in the sports world besides Electronic Arts, and Sega continued to push the bar as it moved towards creating a true identity for its sports games.

The results would soon truly take its sports games to the next level.

The Birth of Sega Sports

The actual start of the Sega Sports brand can best be traced to efforts by Sega to change the overall look of its packaging, starting in 1992. That year, a special marketing team was created within the company, and it was tasked with redefining the presence and image of Sega as a whole. The search began for a new ad agency that could consolidate Sega’s properties and style into one that was more uniform. Though many longtime Sega fans were quite familiar with (and even fond of) the standard black grid packaging design, it was not considered to be attractive to new consumers who were still on the fence about which console to buy.

Sega of America’s Vice President of Marketing Edward Volkwein and Director of Marketing, Brand/Product Management Diane Fornasier hired Dennis Moore Designs to redesign the packaging for Genesis, Sega CD and Game Gear releases. By 1993, all hardware and titles were sporting packaging consisting of vertical bands of colors – red for Genesis, blue for Sega CD and purple for Game Gear – that made them instantly recognizable on store shelves. At the same time, Volkwein and Fornasier worked with Director of Software Marketing Al Nilsen and Group Director of Marketing Doug Glenn to contract a new ad agency. They found Goodby, Berlin & Silverstein, the group that went on to create the famous “Sega Scream.” $65 million was allotted for advertising in 1992, increasing to $95 million the next year. Sega of America finally had the distinctive look it needed, and it had the advertising budget to take on the competition.

During this period, sports titles were still integrated into the general game line up, with little distinction from other genres such as fighting, platformers and shooters. The in-house library of sports titles was still small overall, with individualized marketing and different producers overseeing separate teams on each project. Sega at this point had no specialized product strategy for sports titles, and Product Manager Hugh Bowen was placed in charge of sports titles under Al Nilsen. Doug Rebert took over when they fell under Fornasier’s watch, maintaining the semi-structured plan that had been in place for sports games for the past several years.

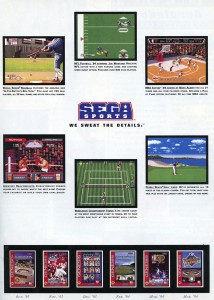

This changed in 1993, when Sega finally decided to organize its sports titles under a single banner. The choice had not been made at staff meeting or through an internal memo but was actually the culmination of years of business practices that galvanized sports game development within Sega to a point where it became viable to give it an identity of its own. The popularity of the genre in America and the success of competitors like Electronic Arts convinced SOA management that it was worth consolidating its sports titles. In a phone interview, former SOA Executive Producer of Sega Sports Product Development Scott Rohde narrated to Sega-16 how the official brand name came about through an almost comical feat of consultation. “We wanted to build a sports line that was competitive with EA Sports, so they (SOA management) said ‘we’re going to commission a study to figure out what we should call the Sega sports line.’ They had a bunch of consultants come in, do this, that and the other, and what they came back with was ‘we should call it Sega Sports.'” Creative or not, Sega finally had a banner under which it could assemble its sports-related properties. Associate Director of Marketing Doug Rebert, working with Executive Producer and Sega Sports Group Director Wayne Townsend, was placed in charge of the newly-christened line. Dennis Moore Designs returned to create the logo that all Sega-made sports games would bear on the Genesis, Sega CD and Game Gear, and by the second quarter of 1993, everything was in place for the official launch.

Speaking to Sega-16, Diane Fornasier vividly recalled the first appearance of the new line. “Since we invited all third party executives to our ‘Sega Summit’ – including EA – we did not want to make a formal announcement of our Sega Sports brand at that function. However, as we typically did, we spoke to retailers in our break-out meetings to give them a high level understanding of our strategies and plans.” Sega pitched the new brand to retailers in Boca Raton, Florida, in order to prepare them for the upcoming roll-out. “We introduced the Sega Sports brand to retailers at our ‘Sega Summit’ in May of ’93,” Fornasier explained to Sega-16, “and we were able to add it to our packaging for the second half of that year for Wimbledon Championship Tennis, Pebble Beach Golf and NFL ’94 Starring Joe Montana.” New games were being added to the release schedule more fluidly as the year progressed, but it wouldn’t be until the following year that a full packaging roll-out would take place.

First held in 1992, the “Sega Summit” was a closed-door show for retailers only. Here, they were made privy to Sega’s upcoming product line, long before it was shown to the general public and press at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES). The retailers were divided into two groups so that Sega sales representatives and third party developers could offer more personalized orientation about upcoming software and peripherals. The initial evening was for cocktails and relaxation, followed the next morning by powerful and edgy presentations where Sega and licensees would show off their wares for the fourth quarter (October-December). Looking more like a miniature trade show than a friendly get-together, the summit underscored Sega’s aggressive marketing stance. The software giant itself had a large area of the floor that was packed with all of its latest merchandise, and licensees were given “suites,” large hotel rooms where most of the furniture was replaced with kiosks and monitors running demos and video footage of new software.

After a day of spent in the suites, retailers were treated in the evening to game-themed cocktails and dinner, and they would receive special promo items based on the titles featured at that year’s summit. Former Sega Events Director Deborah Hart offered Sega-16 an example of the attention to detail that went into planning such a complex affair. “One fun pre-dinner event was started by playing volleyball on the beach and had celebrity guest Ronnie Lott do a special appearance that evening. We had dinner around a large pool area – beach front. Food was ‘ball park’- themed, and since Ronnie had just signed with the Jets we had green helmets for a ‘make-it-yourself’ ice cream sundae. Special promo items were made and put into SEGA SPORTS branded gym bags. The evening was topped with fireworks that ended with the SEGA SPORTS logo ablaze in the sky.”

Sega Sports made its official debut at the June, 1993 CES. A slew of demo kiosks stood proudly under massive banners, showing several high profile games among over-sized examples of Sega’s new packaging. The Genesis was growing rapidly by this point, thanks to the success of the Sonic games and competitive pricing. The new line up, combined with the fresh designs and a massive marketing budget, showed publishers that the console’s recent domination was not a fluke but the result of quality software and careful and aggressive promotion. It also reaffirmed Sega’s commitment to providing a dedicated sports line for Genesis owners, a major plus against rival Nintendo’s random offerings in the genre.

Sega mass introduced the new label to consumers through print media via the August/September 1993 issue Sega Visions, on the cover and in a four-page spread that detailed an abundance of new games coming for the Genesis and Sega CD, as well as several Game Gear ports, including Joe Montana Football. Even so, the launch took some time to build steam. Though the line was initially scheduled for the Genesis and Sega CD in May, the first commercials didn’t hit television and print until the fall, and packaging had already been almost completely solidified for the rest of 1993’s release schedule. Thus, only a few titles early on were able to display the logo in the upper-right corner. NFL ’94 was the first Sega Sports game to actually advertise the brand individually, featuring a funny ad in the fall of 1993 that had psychiatrists analyzing Joe Montana while boasting about the game’s real players and teams and brazenly promoting “Sega sweats the details” as its slogan.

Sega mass introduced the new label to consumers through print media via the August/September 1993 issue Sega Visions, on the cover and in a four-page spread that detailed an abundance of new games coming for the Genesis and Sega CD, as well as several Game Gear ports, including Joe Montana Football. Even so, the launch took some time to build steam. Though the line was initially scheduled for the Genesis and Sega CD in May, the first commercials didn’t hit television and print until the fall, and packaging had already been almost completely solidified for the rest of 1993’s release schedule. Thus, only a few titles early on were able to display the logo in the upper-right corner. NFL ’94 was the first Sega Sports game to actually advertise the brand individually, featuring a funny ad in the fall of 1993 that had psychiatrists analyzing Joe Montana while boasting about the game’s real players and teams and brazenly promoting “Sega sweats the details” as its slogan.

The next year, the logo was prominently displayed on all of Sega’s sports titles, including NBA Action, the technologically impressive (and expensive) Virtua Racing and World Series Baseball, which made history by being the first console sports title to boast digitized players. The effort to increase brand awareness also expanded to events beyond those solely associate with sports, such as a children’s event in December of 1994 in which actress Meryl Streep and her family made an appearance. The Game Gear was finally fully included from then on, and the company aggressively marketed the line whenever possible, including an NFL demo tour at stadiums and at the Super Bowl XXIX “NFL Experience” in January of 1995. Furthermore, Sega continued to hold its “Sega Summit” activities in 1994 and 1995, both at Disney’s Contemporary Resort in Orlando, Florida.

With a massive presence on all of Sega’s machines and in the media, and covering virtually every possible sport, Sega Sports was quickly becoming a pivotal part of Sega’s plan for success.

Pingback: Sega-16.com Explores the History of Sega Sports | Put That Back