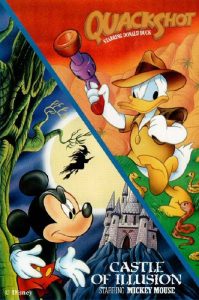

For many gamers who grew up with the Genesis, some of their fondest memories with the console came from the series of early Disney games published by Sega. Long before furry mascots flooded Sega’s 16-bit console, there was a mouse and a duck, and they starred in two of the most wonderful platformer’s in the system’s library. Castle of Illusion Starring Mickey Mouse and Quackshot Starring Donald Duck, were the high point of pre-Sonic 16-bit platforming, and they were followed up by the co-op dazzler World of Illusion. The first game in the beloved Illusion series, Castle of Illusion, is widely hailed as a Genesis classic, and fans still regard its unique blend of Disney charm, simple gameplay, and beautiful presentation as one of the prime examples of platforming excellence of the era.

For many gamers who grew up with the Genesis, some of their fondest memories with the console came from the series of early Disney games published by Sega. Long before furry mascots flooded Sega’s 16-bit console, there was a mouse and a duck, and they starred in two of the most wonderful platformer’s in the system’s library. Castle of Illusion Starring Mickey Mouse and Quackshot Starring Donald Duck, were the high point of pre-Sonic 16-bit platforming, and they were followed up by the co-op dazzler World of Illusion. The first game in the beloved Illusion series, Castle of Illusion, is widely hailed as a Genesis classic, and fans still regard its unique blend of Disney charm, simple gameplay, and beautiful presentation as one of the prime examples of platforming excellence of the era.

As polished as the fluid and tight gameplay, excellent visuals, and enjoyable music of Castle of Illusion were, its charm extends beyond that. There’s a certain element to Disney productions that makes them timeless, even when technology has advanced and consumer tastes have shifted. What makes Castle of Illusion so memorable is how faithfully it recreated the personality of its source material. That devotion is the key element and the secret to its enduring favor among Sega fans. Today’s powerful home machines make this an easy feat, but at the turn of the ‘90s, when the Genesis was still in its infancy and most consoles paled in horsepower to arcade boards and home computers, it was a much harder vision to realize.

A Classic Game Takes Form

Castle of Illusion arrived early into the Genesis’ lifespan, when Sega was still trying to carve out an identity for the fledgling machine. It shares the tale of an evil witch named Mizrabel, who kidnaps (mousenaps?) Minnie Mouse out of jealousy of her beauty and popularity. Mickey pursues the witch to her castle, where he must brave multiple stages of danger to collect the magic gems he needs to create a rainbow bridge to Minnie’s tower prison. The plot was right out of a Disney cartoon, and the union of Mickey Mouse and the new 16-bit hardware sounded like a perfect match.

Of course, more bits don’t necessarily equate to better games, particularly those that have the burden of doing justice to such a highly regarded brand. Few names are bigger than Mickey Mouse, and bringing a faithful rendition of such a well-known character to a console that was facing a seemingly insurmountable battle against Nintendo was a daunting task. Given Sega’s minuscule console presence in the U.S., convincing Disney to come aboard was something of a coup. Indeed, securing the license was major feather in the cap of Sega of America President Michael Katz. Along with names like Michael Jackson and Joe Montana, Disney’s mascot was at the forefront of Sega’s licensing barrage, bringing first-rate names to its games in North America. As odd as it may sound, getting the rights to Mickey Mouse wasn’t as easy as negotiating with someone like Michael Jackson. In that case, talks could be held directly with the Gloved One, and he either agreed or he didn’t. With a cartoon character, things were a bit more complicated. Companies such as Disney are quite protective of their intellectual properties. In 1976, the cartoon giant lobbied Congress heavily to overhaul existing copyright laws. Disney’s rights to Mickey Mouse were originally protected for a maximum of 56 years under legislation passed in 1909. The 1976 expansion increased corporate rights to 76 years, ensuring Mickey Mouse would be a Disney property until 2003. In 1998, the company pushed for another increase, and the famous rodent was secured until 2023. So impactful was Disney’s lobbying that the changes in copyright law since 1976 are often referred to as the “Mickey Mouse Curve.”

For this reason, Sega had to give the utmost assurance that Disney’s mascot would not be mistreated. It also had to show that the Genesis was viable enough for a license. Over the course of several meetings with Disney representatives, Katz and marketing head Al Nilsen hashed out its plan to add the cartoon icon to Sega’s lineup of licensed stars, which included LA Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda, boxing champ James “Buster” Douglas, and Dick Tracy. A deal was reached, and Sega soon began promoting the game in its advertising, with an early image appearing in a 1990 pack-in poster. Here, the game was simply called Mickey Mouse.

With the license safely guarded, the task of bringing Disney magic to Sega’s console was placed in the capable hands of Director Emiko Yamamoto, who was credited as “Emirin” due the common publisher policy of era that prevented staff from using their real names (it was thought that pseudonyms would protect them from poaching by other developers). Castle of Illusion was Yamamoto’s first game, and she thought long and hard about ideas that could represent interesting ways to bring a fantasy world to life. Though she was working with the most famous mascot in the world, she decided to pay little regard to difficulty and conventionality. Instead, she focused on making something that would both represent the degree of quality for which Disney was known and stand out on the console. One thing was clear to everyone involved: they didn’t want to make a game that was simply centered around Mickey Mouse. There was a desire to include larger elements of the Disney universe into the game world, enough to illustrate how well everything fit into the company’s decades-old lore. Yamamoto summed up the developers’ guiding vision of what the design should be in an interview for the game’s 2013 remake on Xbox 360, PlayStation 4, and Steam: “the essence of Disney, a positive world of dreams, peace, and imagination.” Several of the company’s classic films influenced the path the team took towards those goals, and their marks are visible in many of Castle of Illusion’s enemies and bosses. The clock tower boss is obviously Willie the Giant from the 1947 classic cartoon Fun and Fancy Free. The main antagonist Mizrabel, for one, was inspired by two of Disney’s most famous villains. In her initial form, that of an old woman, she clearly resembles Queen Grimhilde from Snow White. When players battle her at the end of the game, she transforms into a figure that is eerily reminiscent of Maleficent, the main antagonist from Sleeping Beauty. Her name, however has a decidedly non-Disney origin. The play Les Misérables, based on the 1862 Victor Hugo novel, was widely popular at the time, and Mizrabel’s moniker is a derivation of its title.

The Mouse Is in the Details

Aware of the reputation Disney’s animated movies had for their fluid and realistic look, Yamamoto’s team paid special attention to Castle of Illusion’s animation. They poured over Disney films, often frame-by-frame, trying to emulate the company’s iconic style by mimicking as many animation techniques as possible. The large range of emotion Mickey conveyed throughout his movements required large amounts of animation, which directly affected the level design. For example, Mickey’s jump animation was modeled to convey his full range of motion, and it required a rethinking of how obstacles were placed in each stage. “We wanted to fully express his body movement,” Yamamoto told Game Informer in 2013, “so we added more frames of animation. As a result, his jump ended up being longer than a jump would be in a normal game, so we had to design the levels so that the distance of his jump worked.”

Mickey’s famous idle animation also emerged from this emphasis on emotion. Sonic may be known for tapping his foot when left in one spot, but he actually owes the trait to the famous mouse. Arguably the first character to ever feature an idle animation, Mickey was a stark contrast to Sega’s hedgehog in tone when left in one place. Seemingly content with the player’s decision to stand still, the character swayed his hips back and forth, a large smile etched on his face. Mickey also had a humorous animation when he stood too close to the edge of a platform or cliff. Both animations were first brought to Art Director Takashi Yuda by Castle of Illusion’s main programmer (known only by his pseudonym, “Ore”) and one of the animators. They showed him an early version of the idle animation, and he was so impressed that he agreed to include them in the game. Video game characters at the time were not known for showing emotion under different circumstances, and the inclusion of these specific animations gave Mickey more personality that he had ever previously had in a video game. They also made Castle of Illusion a much more advanced type of platformer than others, giving Sega a title with the kind of presentation it needed to promote its powerful 16-bit console. Nilsen even emphasized the game’s use of animation to express Mickey’s emotions during his presentation of the Genesis on the December 6, 1990 episode of the Computer Chronicles, where he demoed some Castle of Illusion gameplay for the hosts.

Along with the importance of expressing emotion, the development team’s research into Disney film animation revealed to them another attribute that was found in each movie: consistent motion. Even when there wasn’t anything really happening onscreen, there was some amount of movement. The goal was to make each movie environment seem alive and vibrant no matter the scene. This technique would present something of a challenge for Yuda and his art team. The limited VRAM of the Genesis was not typically used at the time to focus on animation, so Yuda and his artists had to work with the programmers to practically rebuild the system “from the ground up” to allow all the animation to fit. From there, they adjusted each character’s movement pixel-by-pixel to maintain smooth control.

The backgrounds in Castle of Illusion were just as important. There was a conscious effort to make sure that their visual quality didn’t hinder gameplay. While there was plenty of animation and movement in them (clouds, swaying trees, etc.), the team took steps to not make them too active. Moreover, effects like added lighting to platform edges were used so that players would always be able to see where they had to jump.

That last point is an important one to note, as it was just a sample of the steps the developers took to achieve a perfect balance between presentation and control. Castle of Illusion’s visuals and animation were ground-breaking, but its gameplay was not sacrificed to make them happen. Yamamoto’s team was very much aware that they were making a platformer, and the gameplay was the product’s key feature. That was why they had players press the jump button or press down after jumping to use Mickey’s bounce attack. It was felt that if the attack occurred automatically after jumping, then players wouldn’t feel like they were in complete control. Also, enemies were placed in sets so that players could bounce off them in sequence, a mechanic that required timing and a bit of skill.

Disney’s role in development was extensive, but the delicate symmetry that was achieved arose from the contributions of several key people within Sega and Disney on both sides of the Pacific. Contrary to popular belief, Castle of Illusion’s development was not confined merely to Japan. Sega of America and Disney both had major influence and direct involvement with the game’s design. Along with the actual design and programming, Disney Producer Stephen Butler collaborated with Sega of America’s Senior Producer Jim Huether to ensure that Castle of Illusion remained true to the Mickey Mouse character. Working from California, Butler and Huether coordinated with Sega and Disney in Japan and provide suggestions and feedback. For example, when Yuda was working on the dragon boss inside the milk bottle in the library stage, he couldn’t decide what to use for its body. He was sent licorice from Sega of America as a suggestion, and he quickly became hooked on the tasty treat (much to the chagrin of his colleagues). One day, he was holding a long piece of licorice in his mouth and breathing through it as a straw, and the aroma permeated the entire room. Yuda was inspired by the effect the candy had on him and used it as the body for his dragon boss, one of more memorable in the game. Butler and Huether also helped improve certain elements of the gameplay. “Stephen Butler and myself drove the updates to the design and improvements to the gameplay,” Huether told Sega-16 in an interview for this piece, “to make it both a game that Disney would approve and to give it some unique gameplay (such as the very easy mode so parent could play with their little kids).” Together, they helped guide the design so that it captured what players would expect from a Mickey Mouse video game.

Castle of Illusion butt-stomped its way onto the Genesis on November 20, 1990, garnering kudos from many of the available gaming magazines. Video Games and Computer Entertainment said, “Castle of Illusion is, quite plainly, one of the most fabulous run-and-jump games ever created,” and Electronic Gaming Monthly stated that “Mickey is the game which Disney himself would be proud of.” High praise indeed, and it cemented the game as a cornerstone of the early Genesis library during its important pre-Sonic years.

Yamamoto also brought her platforming vision to the Master System version of Castle of Illusion as designer and director. Far from a port, it was a thorough reimagining of the game concept that wisely chose to play to the machine’s strengths with a new version of Mickey’s adventure rather than just a quick conversion. It was ported to the Game Gear shortly thereafter. Yamamoto followed up with Quackshot Starring Donald Duck and World of Illusion, giving her an impressive body of work in only a few short years and a trilogy of Disney classics on the Genesis. Sometime in the mid-1990s, she had left Sega to join Disney Interactive, where she remained until 2016.

As stated earlier, a remake of Castle of Illusion was released for consoles and Steam (PC) in September 2013. Surprisingly, it wasn’t the first time that Sega of America had attempted to bring back Mickey’s most popular Genesis adventure. Interestingly, it had never tried to do so without Yamamoto’s approval first. During her nearly two-decade tenure at Disney, multiple prototypes from different studios had been presented to her by Sega, but only the one by Sega Studios Australia (SSA) was able to recapture what she felt while making the original game. It was a perfect fit for both companies, and its timing was perfect. Sega and Disney were already engaged in talks about new projects, and the decision to remake Castle of Illusion came in 2011. SSA Studio Director Marcus Fielding had his team work on the prototype with the expressed purpose of presenting it directly to Yamamoto. After her initial positive reaction to their early work, Fielding and several members of SSA flew to Sega of Japan to present the prototype to Yamamoto in person. Their anxiety and apprehension was quickly dispelled by Yamamoto’s pleasant demeanor. She was extremely pleased with the team’s direction for Mickey Mouse and was genuinely excited about working with the studio. The game was warmly received, and Yamamoto’s work received another validation of its quality and persisting popularity.

No Illusions about Greatness

Yamamoto is no longer with Disney, having left in 2016. In the intervening years between Castle of Illusion and her departure, she served as producer on many other Disney titles, including the Magical Quest and Kingdom Hearts series, never straying too far from the Mouse that initiated her in the gaming industry. Even today, she looks back fondly on her debut Genesis title, and she recognizes what has made it such a fan favorite. “When I was thinking about what people remember fondly about the game… at the time,” she confessed in 2013, “I think it was enjoying the thrills and getting the timing right when they played it. I think enjoying the game world, and experiencing the fantasy world of Disney were a big part of it, too.”

Sega had to delist the Castle of Illusion remake from consoles stores and Steam in September 2016 due to what Sega referred to as “an expiration of business terms.” As of April 2017, has since been made available again on Steam, Xbox Live, and the PlayStation Store. It’s also been made backward compatible on the Xbox One, but it’s anyone’s guess as to how long this new availability will last. While not as bad as the fate that befell updates to two other Sega classics, After Burner Climax and OutRun Arcade Online – those games falling victim to expiring licenses with Grumman-Northrop and Ferrari – it is still frustrating to see how uncertain its sustained availability is. This unfortunate situation is one of the many drawbacks of digital-only distribution, but in Castle of Illusion’s case the blow has been a bit harder. Those who pre-ordered the PlayStation 4 version received the Genesis original as a bonus, giving a whole new generation of gamers the chance to experience the game in its 16-bit form. It was also offered for free in April 2013 for anyone with a PlayStation Plus subscription. Now that it has been removed or made harder to acquire, the only way for many people to enjoy this wonderful title is via the original cartridge. From a certain perspective, perhaps that is best. To play Castle of Illusion on the Genesis console is to appreciate the amazing technical hurdles Yamamoto, Yuda, and the development team overcame to make it possible. Maybe, it’s possible to attain a greater appreciation for their work when played as first intended. That’s an optimistic appraisal of an otherwise lamentable reality, but when faced with no other options, a glass half-full is better than none at all.

Sources

- Butler, Stephen. Email interview. 12 Dec. 2014.

- “Castle of Illusion Starring Mickey Mouse – Behind the Scenes. YouTube. uploaded by Polygon 30 May 2013.

- Haske, Steve. “Why ‘Castle of Illusion’ Getting Delisted Sucks for Everyone.” Inverse Ent.,7 Sept. 2016.

- Huether, Jim. Email interview. 7 Feb. 2015.

- Lachel, Cyril. “Castle of Illusion: What Did Critics Say Back in 1991?” Defunct Games, 14 July 2014.

- Schlackman, Steve. “How Mickey Mouse Keeps Changing Copyright Law.” Art Law Journal. 15 Feb. 2014.

- Turim Tim. “Original Castle Of Illusion Dev. Discusses Animation And Witch Naming.” Game Informer, 13 Aug. 2013.